Evaluating Al-Hatorah's Digital Repository: Exploring Its Excellent Tanakh and Talmud Commentaries, and More

Strong in medieval commentaries on Tanakh and Talmud, many of them recent critical editions. Some small bibliographical nitpicks

Part of series on contemporary resources for Jewish study. Written in preparation for my upcoming presentation on June 19, where I’ll be sitting with Hillel Novetsky of Al-Hatorah, at a session at the conference “Editions of Classical Jewish Literature in the Digital Era”. See my previous announcement here: “Announcement: My upcoming presentation: ‘An Overview of Digital Resources for the Scholarly Study of Rabbinic Texts’ “. This blogpost is based on my review of Al-Hatorah that was included in my “Guide to Online Resources for Scholarly Jewish Study and Research - 2023”. That guide was written at the beginning of 2022, so some of the info here may be somewhat out of date.

Intro

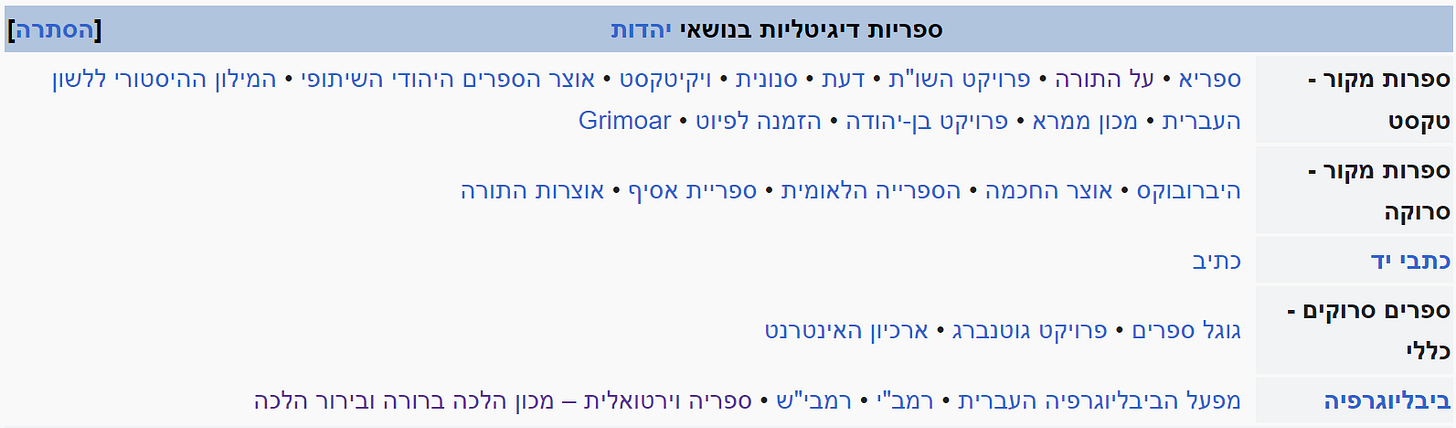

A Wikipedia entry on Al-Hatorah was a desideratum when this piece was first written (beginning of 2022), there is now an entry in the Hebrew Wikipedia: על התורה – ויקיפדיה. I also included Al-Hatorah in the Wikipedia table that I created of “digital libraries focusing on Jewish topics” (תבנית:ספריות דיגיטליות בנושאי יהדות), here. Screenshot:

Al-Hatorah vs. Sefaria

Both Al-Hatorah as well as Sefaria are very user friendly and powerful both for looking up references, as well as for studying. However, not all of the transcriptions on Al-Hatorah are complete.

Al-Hatorah has more developed tools for serious study. While Sefaria has a bit of a cleaner interface and more modern UX/UI with lots of whitespace. The UX/UI of Al-Hatorah is quite similar to that of “Bar Ilan Responsa Project,” in that the Tables of Content are set up as “trees”.

Another important difference between Sefaria and Al-Hatorah is that the former is open access while the latter is copyrighted. This is probably due to the kind of original content of the latter. Relatedly, Sefaria has extensive tools for exporting data, such as via API and through manual downloads, that Al-Hatorah doesn’t have.

The People Behind Al-Hatorah

From the About page: “ALHATORAH.ORG was founded by Rabbi Hillel & Neima Novetsky and their children, Yonatan, Aviva, Ariella, and Yehuda. Hillel is a musmakh of RIETS (YU) and earned an MA in Jewish History from Bernard Revel Graduate School and a PhD in Bible from Haifa University. Neima earned an MA in Bible from Bernard Revel Graduate School (YU) and teaches in Torah institutions in Israel. The content of the website is the product of an ongoing, worldwide, collaborative effort of Rabbis, scholars, educators, and laypeople.”

See also their mission statement and Who We Are (listed on the Advisory Board there: Prof. Uriel Simon, Prof. Haym Soloveitchik, Prof. Richard Steiner, and more).

Strong in medieval commentaries on Tanakh and Talmud

Al-Hatorah is especially strong in medieval commentaries on Tanakh and Talmud. It is also good on the basic texts of a typical yeshiva curriculum - Tanakh, Mishna, Talmud, and their commentaries. It is fairly weak in the genres of Kabbalah, Liturgy, Jewish Thought, Chasidut, Musar, and Responsa, all of which are major sections in Sefaria.[1]

Full “library tree” here.

See the full list of digital editions. The full range of high-quality editions is quite impressive.

Some of the works available there - many from recent critical editions

Al-Hatorah has often secured the rights to use the best edition of a book available. In many cases, especially for medieval Torah commentaries, the version on the website is in fact better than any edition available in print. see for example, the footnotes to Ramban’s Torah commentary, which includes textual variants from all available manuscripts and the first two printed editions, surpassing the Chavel edition by a longshot.[2]

Some of the works available there (many from recent critical editions):

Targum Yerushalmi - Neofiti (תרגום ירושלמי - ניאופיטי).

New digital edition of Rashi on Torah, Leipzig manuscript.[3]

Reconstruction of the Lost Parts of Rashbam's Torah Commentary.[4]

Additional new digital editions of Torah commentaries, with introductions: ibn Ezra, Yosef Bekhor Shor, and more; see list here (under “נושאים פרשניים”).

New digital edition of Rif (ed. E. Chwat).[5]

Rashbam's Commentary on Avodah Zarah (ed. H. Gershuni).

Mishna MS Kaufmann (ed. D. Be’eri).

Mishnat Eretz Yisrael - modern scholarly commentary on Mishnah. This commentary is also in Sefaria, as mentioned in its entry.

Steinsaltz-Koren commentary on Talmud Bavli in Hebrew (Sefaria has the English translation and commentary, as mentioned in its entry.)

Visualizations. Very interesting visualizations: timelines, maps, and lists.

Intros, with footnotes to latest academic research:[6]

Discussion of bibliography, and of the corpus of texts

Each digital edition in that list has the important bibliography details noted, such as the modern editor of the edition used, the manuscript it is based on, as well as other info. As of this writing, around 320 works are listed there, and around half of them are medieval Torah commentaries (in chronological order; from Saadia Gaon to Abravanel).

Of these medieval Torah commentaries, around a third are original editions of Hillel Novetsky and the Al-Hatorah team themselves (to be exact, 49 out of 160 are marked “[מהדורת רב הלל נובצקי [ועל־התורה”). Only Torah commentaries editions are original editions of Hillel Novetsky (with or without the Al-Hatorah team); all other works in other genres, such as the “Second Temple Literature'', Hazalic works, commentaries to the Talmud, are attributed as being editions of “Al-Hatorah” or other sources. Around 71 of the total 320 works listed are marked as being original editions of Al-Hatorah (“מהדורת על־התורה”). For many of them, it is noted that they are in the process of being “prepared” (“בהכנה”).

It would be interesting to do a comprehensive review of the quality of the editions used between Al-Hatorah, Bar-Ilan Responsa Project and Sefaria. Sefaria typically uses the standard print editions, so there’s definitely room for improvement there.

Some small bibliographical nitpicks

Some bibliographical entries are missing from the List of Editions page, and don’t have bibliographic info on their page either. For example, Megillat Ta’anit (מגילת תענית) is missing, and it’s not noted anywhere what the Al-Hatorah edition is based on.

Other examples of missing bibliographic info: R’ Ahai’s She’iltot (שאילתות); R’ Saadia Gaon’s Azharot (ר׳ סעדיה גאון אזהרות תרי״ג מצוות).

There are also works that are in the Library tree, but are not yet found. For example, Mekhilta D’Rashbi (מכילתא דרשב״י שמות), found in the tree at בית שני > מדרשי הלכה > מכילתא דרשב״י שמות. When clicking, get error “הטקסט לא נמצא במאגר המידע”.

Conclusion

Al-Hatorah has some incredible digital editions of medieval commentaries on Tanakh and Talmud. As for works outside of that, it is a work in progress, and an exciting one at that. The future's looking bright!

[1] Most glaringly, the Zohar is not currently included in the corpus of works in Al-Hatorah.

[2] Pointed out by a commenter to the original blogpost.

[3] See discussion started by R’ Adiel Breuer at this Otzar HaHochma forum, dated 25-Jan-2016.

[4] From the intro there: “The reconstructed interpretations of Rashbam presented on these pages are a preliminary version from 2015 of the analysis conducted by Hillel Novetsky of material which he discovered in various manuscripts. An updated version of these texts based on his dissertation (2020) can be accessed at https://mg.alhatorah.org [...].”

[5] See interview with Chwat on this edition on Seforim Chatter podcast: “With Dr. Ezra Chwat discussing the Rif (Rav Yitzchak Alfasi, 1013 – 1103) and his new critical edition”, #97, October 10, 2021.

[6] Full list here. May of the linked pages only have headers, with no content.

[7] Footnote 1 there: “1 This section incorporates information from M. Kahana, "The Halakhic Midrashim" in The Literature of the Sages Part II, ed. Safrai et al. (Assen, 2006): 3-105 (hereafter: Kahana), and G. Stemberger and H. Strack, Introduction to the Talmud and Midrash (1996, hereafter: Stemberger and Strack).”