Pt1 ‘Leḥem Oni’ vs. Luxury: ‘The Bread of Affliction’ and the Halakhic Boundaries of Passover Matza (Pesachim 35b-37b)

This is the first part of a three-part series. The outline of the series is below. The series is in honor of Passover. Chag Sameach!

This sugya discusses the halakhic requirements for fulfilling the mitzva of eating matza on Passover. Drawing on close biblical readings and a wide array of rabbinic interpretations, the passage probes what qualifies as leḥem oni—the "bread of affliction" ( Deuteronomy 16:3).

The Biblical sources for the requirement to eat Matzah on Passover

See Wikipedia, “Matzah“, section “Biblical sources“:

Matzah is mentioned in the Torah several times in relation to the Exodus from Egypt:

That night, they are to eat the meat, roasted in the fire; they are to eat it with matzo and maror.

— Exodus 12:8

From the evening of the fourteenth day of the first month until the evening of the twenty-first day, you are to eat matzo.

— Exodus 12:18

You are not to eat any chametz with it; for seven days you are to eat with it matzo, the bread of affliction; for you came out of the land of Egypt in haste. Thus you will remember the day you left the land of Egypt as long as you live.

— Deuteronomy 16:3

For six days you are to eat matzo; on the seventh day there is to be a festive assembly for Hashem your God; do not do any kind of work.

— Deuteronomy 16:8

The term ‘Bread of Affliction’ (‘Leḥem Oni’)

On the term ‘Bread of Affliction’ (‘Leḥem Oni’), see Hebrew Wiktionary, “לחם עני”, section “גיזרון”, my translation, with slight adjustments:

The expression appears in the Bible only once. The Talmudic sages disagreed about the root of the word oni (עוני):

One view derives it from ani (ע־נ־ה Aleph), meaning "poverty,"1 while another connects it to ma‘aneh (ע־נ־ה Bet), meaning "response" or "narration."

This disagreement has interpretive and even halakhic implications—for example, the prohibition against kneading the festival matza with wine or honey, or baking it as a scalded dough.

Babylonian Talmud, Pesachim 36a (=our sugya):

“ ‘Leḥem oni’—this excludes dough kneaded with wine, oil, or honey.

What is R’ Akiva’s reasoning?

Is it written leḥem oni [with a vav, meaning ‘poverty’]?

No, it is written leḥem oni [without a vav, suggesting ‘of affliction’ or ‘that one responds over’].

But R’ Yosei HaGelili says: Do we read it as ani [poverty]? No, we read it as oni.

And R’ Akiva: That we read it oni supports Shmuel’s interpretation, who said: ‘Leḥem oni’—bread over which many things are said.”

The word was also homiletically interpreted like on in aninut (“mourning”) (Pesachim ibid., in our sugya).

Rashi: “[It is] bread that reminds us of the suffering (oni) we endured in Egypt.”

Overview of the sugya: Matzah made from ingredients that are second tithe (ma’aser sheni), first fruits (bikkurim), untithed (tevel), rich ingredients (wine, oil, honey); milk, boiled (halut), warm water (poshrin), shaped, thick

According to our sugya, the “bread of affliction” excludes various types of dough and bread that, while technically unleavened, fall short of the symbolic and legal criteria.

The discussion in the sugya opens with a basic principle: only matza made from grain that is itself permissible to eat—untainted by other prohibitions like tevel (טבל - produce not tithed)—can fulfill the commandment.

From there, the sugya unfolds into a series of debates touching on the ritual status of second tithe, first fruits (bikkurim), and matza prepared with rich ingredients like wine, oil, honey, or milk.

It also examines the implications of preparation methods: matza that is boiled (חלוט), kneaded with warm water, shaped decoratively, or baked in large or thick forms is either outright disqualified or deemed problematic due to the risk of leavening.

At the core of these debates lies the tension between biblical ideals and practical halakhic boundaries. While the phrase matzot matzot is used midrashically to expand the range of acceptable matzot, the requirement of leḥem oni repeatedly serves to limit that expansion—excluding luxurious or celebratory forms of matza incompatible with the Passover ethos of poverty, affliction, and speed.

The rabbis also raise concerns about customary practices and communal perceptions, especially regarding shaped (סריקין המצויירין) matza and dairy doughs.

Culinary Typology and Technical Knowledge

The passage reveals a culinary taxonomy, distinguishing between numerous bread varieties and preparation methods:

Baking methods: Standard oven baking, sun-drying, pot cooking, pan-frying

Bread varieties: Fine (pat nekiya) versus coarse (hadra'a), thick (pat ava), decorative (serikin), half-baked (hina)

Specialized pastries: Sponge cakes (sufganin), honey cakes (duvshanin), spiced cakes (iskretin)

Hydration techniques: Me'isa (flour into boiling water) versus ḥalita (boiling water onto flour)

Comparative Technology and Expert Knowledge

The sugya reveals insights about technological differentials between institutional and domestic contexts:

Temple vs. household production

Rav Yosef's objection to comparing ordinary matza with Temple showbread is particularly revealing. He identifies five technological advantages in Temple baking:

Expert personnel ("diligent (זריזין) [priests]")

Superior ingredients ("well-kneaded (עמילה) dough")

Premium fuel ("dry wood" vs. "moist wood")

Controlled temperature ("hot oven (תנור)" vs. "cool oven")

Advanced equipment ("metal oven" vs. "clay oven")

Professional vs. domestic bakers

The discussion between R' Tzadok and his son reveals both professional specialization and social stratification. Whether the restriction on decorative matza applied to professional bakers or to ordinary people, the passage acknowledges distinct skill levels and production methods between these groups.

Outline

Intro

The Biblical sources for the requirement to eat Matzah on Passover

The term ‘Bread of Affliction’ (‘Leḥem Oni’)

Overview of the sugya: Matzah made from ingredients that are second tithe (ma’aser sheni), first fruits (bikkurim), untithed (tevel), rich ingredients (wine, oil, honey); milk, boiled (halut), warm water (poshrin), shaped, thick

Culinary Typology and Technical Knowledge

Comparative Technology and Expert Knowledge

Temple vs. household production

Professional vs. domestic bakers

Luxury vs. ‘Leḥem Oni’: ‘The Bread of Affliction’ and the Halakhic Boundaries of Passover Matza (Pesachim 35b-37b)

Excluding Untithed Produce (Tevel) from the Mitzva of Matza (Deuteronomy 16:3)

Debate re validity of Second Tithe Matza

R' Yosei HaGelili: Second Tithe Matza is invalid, since need Mourning-Eligible Matza (Deuteronomy 26:14)

R' Akiva: Second Tithe Matza is valid, but matza with wine, oil, or honey is invalid

Dispute Over Kneading Dough with Rich Ingredients: wine, oil, or honey; Spreading vs. Kneading

Milk-Kneaded Dough

Limits and Exceptions in Fulfilling the Mitzva of Eating Matza: matza made from Bikkurim and Second Tithe

R' Yosei HaGelili: matza made from bikkurim is invalid by derivation from Exodus 12:20

R' Akiva: matza made from bikkurim is Invalid by Analogy to Bitter Herbs; but Second Tithe matzah is valid

Anonymous baraita: matza made from bikkurim is invalid by derivation from Exodus 12:20; But Second Tithe matzah is valid, derived from the Biblical repetition of “matzot”

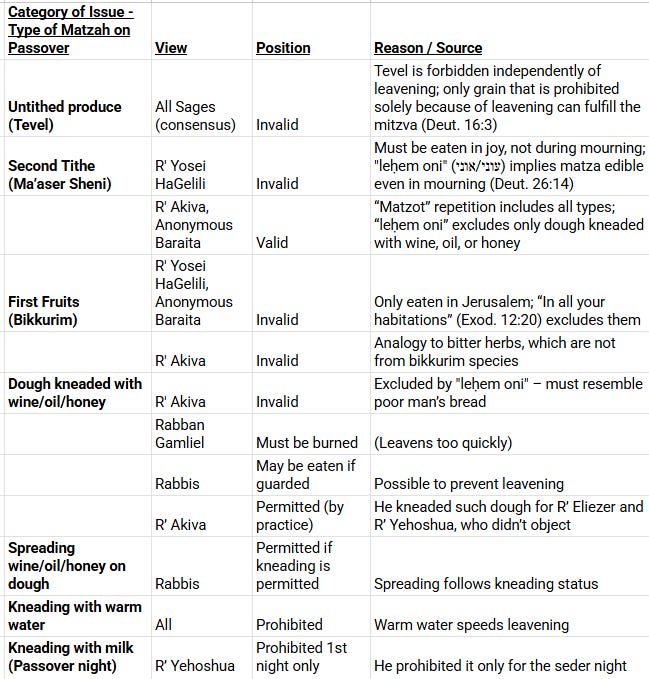

Appendix (Interlude) 1 - Table Summarizing Part 1- summarizing the halakhic rulings and debates so far, around what kinds of matza are valid for fulfilling the mitzva on Passover, based on the sugya

Appendix (Interlude) 2 - “And he didn’t say anything”

“I asked all my teachers, but they didn’t tell me anything“ (Bava Metzia 114a)

“I asked all my teachers, but they didn’t tell me anything“ (Bava Batra 127a)

Tacit Approval or Unaware? Tefillin Straps, Colored Wool, and the Limits of Inference from Silence (Menachot 35a)

Silent Consent: Two Stories Relating to inference from silence of halachic approval (Shabbat 29b)

The iron sulfate (Kankantom) Controversy: R’ Meir Between R’ Akiva and R’ Yishmael (Eruvin 13a)

Continuation - Luxury vs. ‘Leḥem Oni’: ‘The Bread of Affliction’ and the Halakhic Boundaries of Passover Matza (Pesachim 35b-37b)

Defining “Poor Man’s Bread” and the Status of Ashisha (Deuteronomy 16:3): Exclusions from “Poor Man’s Bread”; Inclusion of Fine Flour Matzot

Ashisha as a Sign of Luxury; Dispute Over the Meaning of Ashisha (II Samuel 6:19, Hosea 3:1)

Dispute About “Thick Bread” on Passover

Definition of “Thick Bread”: Rav Huna’s Definition of Thick Matza; Rav Yosef’s Challenge Based on Practical Differences; Rejection of the Analogy to Showbread

The Meaning of “Pat Ava” and Its Attribution in Rabbinic Tradition:

Chain of Attribution

Definition of the Term; Etymology and Regional Usage

Debating Shaped Matza and Leavening Risks

Permissibility of Different Types of Matza

Baitos ben Zonin’s Challenge

Rabban Gamliel’s Practice and R' Tzadok’s Explanation

Alternative Version of R' Tzadok’s View

R' Yosei’s Ruling on Matza Thickness

Exemption from Ḥalla for Unusual Breads and Cakes: Exemptions for Certain Baked Goods; Definition of Pan-Fried Bread; Cooking Method Affects Obligation

Minimum Bake Standard for Valid Matza

Dispute over Boiled Dough and the Obligation of Ḥalla Separation

Definitions of Me’isa and Ḥalita

Dispute between R' Yishmael ben Yosei and Rabbis

Appendix 3 - Table Summarizing Parts 2-3: Passover Matza Requirements – Rulings by Case and Authority

The Passage

Excluding Untithed Produce (Tevel) from the Mitzva of Matza (Deuteronomy 16:3)

A baraita states that one cannot fulfill the mitzva of eating matza on Passover using grain that has not been tithed.2

This is homiletically derived as follows:

The verse links matza to the prohibition against eating leaven: “You shall not eat leavened bread with it; seven days you shall eat with it matza.” From this, it’s homiletically inferred that valid matza must be edible except for its potential to become leavened.

But untithed produce (=tevel) is prohibited independently of leavening (as its status as untithed produce renders it forbidden). Therefore, it is excluded from the kinds of matza that can fulfill the commandment.

תנו רבנן:

יכול יוצא אדם ידי חובתו בטבל שלא נתקן

[...]

תלמוד לומר: ״לא תאכל עליו חמץ״ —

מי שאיסורו משום ״בל תאכל עליו חמץ״,

יצא זה שאין איסורו משום ״בל תאכל חמץ״,

אלא משום ״בל תאכל טבל״

[...]

The Sages taught:

I might have thought that a person fulfills his obligation to eat matza with untithed produce that was not amended with regard to tithes.

[...]

The verse states: “You shall not eat leavened bread with it; seven days you shall eat with it matza” (Deuteronomy 16:3).

One fulfills his obligation to eat matza with food whose prohibition is solely due to the prohibition: Do not eat leavened bread with it, if it was not preserved in an unleavened state.

This command excludes this grain, which is not prohibited due to the prohibition: Do not eat leavened bread,

but rather due to the prohibition: Do not eat untithed produce.

[...]

Debate re validity of Second Tithe Matza

תנו רבנן:

The Sages taught:

R' Yosei HaGelili: Second Tithe Matza is invalid, since need Mourning-Eligible Matza (Deuteronomy 26:14)

R' Yosei HaGelili states that one might think second tithe matza eaten in Jerusalem is valid for fulfilling the mitzva.

But it’s homiletically derived that in fact such matza is invalid:

The verse refers to “leḥem oni”, “poor man’s bread” (עוני with letter ‘ayin’), which is homophonous with “oni” (אוני - with letter ‘aleph’ - meaning acute mourning).

From this linguistic link, R' Yosei HaGelili infers that valid matza must be permitted to be eaten even in mourning, unlike second tithe, which must be eaten in joy and is forbidden in mourning (Deuteronomy 26:14).3

יכול יוצא אדם ידי חובתו במעשר שני בירושלים,

תלמוד לומר: ״לחם עוני״,

מה שנאכל באנינות.

יצא זה שאינו נאכל באנינות, אלא בשמחה

דברי רבי יוסי הגלילי

I might have thought that a person can fulfill his obligation to eat matza on Passover with matza of second tithe in Jerusalem.

Therefore, the verse states: “You shall eat no leavened bread with it; seven days you shall eat with it matza, the bread of affliction [leḥem oni]” (Deuteronomy 16:3), oni with the letter ayin, i.e., poor man’s bread.

As this is similar to the phrase: Bread of acute mourning [leḥem oni], oni with an alef, it can be inferred that this mitzva must be fulfilled with matza that can be eaten during a period of acute mourning, on the day one’s close relative has died.

This excludes this second tithe, which cannot be eaten during a period of acute mourning but only in a state of joy, as the Torah states: “I have not eaten from it in my acute mourning” (Deuteronomy 26:14).

This is the statement of R' Yosei HaGelili

R' Akiva: Second Tithe Matza is valid, but matza with wine, oil, or honey is invalid

R' Akiva disputes this and interprets the repeated word “matzot” to include (ריבה) all kinds of matza.

The exclusion of “leḥem oni” rather rules out dough (עיסה) kneaded (נילושה) with wine, oil, or honey (luxury ingredients inconsistent with poor man’s bread).

רבי עקיבא אומר:

״מצות״ ״מצות״ ריבה.

אם כן, מה תלמוד לומר ״לחם עוני״?

פרט לעיסה שנילושה ב

יין

ושמן

ודבש

[...]

R' Akiva says:

The repetition of matzot matzot serves to amplify, and teaches that all types of matza may be eaten on Passover.

If so, what is the meaning when the verse states leḥem oni, poor man’s bread?

This phrase excludes dough that was kneaded with

wine,

oil, or

honey,

which is not classified as poor man’s bread and therefore cannot be used for this mitzva.

[...]

Dispute Over Kneading Dough with Rich Ingredients: wine, oil, or honey; Spreading vs. Kneading

תניא:

taught in a baraita:

Dispute Over Kneading Dough with Rich Ingredients: wine, oil, or honey

One may not knead matza dough on Passover using wine, oil, or honey (as R’ Akiva concluded in the previous section).

Dispute over the Status of Such Dough:

Rabban Gamliel: The dough must be burned.

The Rabbis: it may be eaten.

R’ Akiva’s Testimony: He kneaded dough with wine, oil, and honey while serving R’ Eliezer and R’ Yehoshua (on Passover), and they did not object.4

אין לשין עיסה בפסח ב

יין

ושמן

ודבש.

ואם לש --

רבן גמליאל אומר: תשרף מיד,

וחכמים אומרים: יאכל.

ואמר רבי עקיבא:

שבתי היתה אצל רבי אליעזר ורבי יהושע,

ולשתי להם עיסה ביין ושמן ודבש,

ולא אמרו לי דבר

One may not knead dough on Passover with

wine,

oil,

or honey

And if one kneaded dough in this manner,

Rabban Gamliel says: The dough must be burned immediately, as it is leavened faster than other types of dough.

And the Rabbis say that although it is leavened quickly, one can still prevent it from being leavened, and if he does so it may be eaten.

And R' Akiva said:

It was my Shabbat to serve before R' Eliezer and R' Yehoshua during Passover,

and I kneaded for them dough with wine, oil, and honey,

and they said nothing to me by way of objection.

Spreading vs. Kneading

One may not knead dough on Passover with these additives, but some permit spreading (מקטפין) them (on already-kneaded dough).

The Rabbis clarify that one may only spread them if it was permitted to knead them in; otherwise, spreading is also prohibited.

Warm Water: All agree5 that dough may not be kneaded with warm water on Passover.6

ואף על פי שאין לשין, מקטפין בו

[...]

וחכמים אומרים:

את שלשין בו — מקטפין בו.

ואת שאין לשין בו — אין מקטפין בו.

ושוין —

שאין לשין את העיסה בפושרין

[...]

The baraita continues: And although one may not knead dough with these ingredients,

one may spread these substances on the surface of the dough.

[...]

And the Rabbis say:

With regard to dough into which one may knead wine, oil, or honey, one may likewise spread them on the dough,

whereas concerning dough into which one may not knead these ingredients, one may not spread them on the dough either.

And everyone agrees that

one may not knead the dough with warm water, as this will cause it to be leavened quickly.

[...]

Milk-Kneaded Dough

R' Yehoshua tells his sons (in Aramaic) not to knead dough with milk for the first night of Passover but allows it after.

However, a general baraita prohibits dairy-kneaded dough year-round (due to the risk of mixing with meat). If one does so, the resulting bread is prohibited, as a a preventive safeguard.7

כדאמר להו רבי יהושע לבניה:

יומא קמא -- לא תלושו לי בחלבא,

מכאן ואילך -- לושו לי בחלבא.

[...]

תניא:

אין לשין את העיסה בחלב,

ואם לש —

כל הפת אסורה,

מפני הרגל עבירה.

[...]

The Gemara adds that this is as R' Yehoshua said to his sons:

On the first night of Passover, do not knead for me dough with milk,

but from the first night onward, knead my dough for me with milk.

[...]

taught in a baraita:

Throughout the whole year one may not knead dough with milk,

and if he kneaded dough with milk,

the entire bread is prohibited,

due to the fact that one will become accustomed to sin, by unwittingly eating it with meat

[...]

Limits and Exceptions in Fulfilling the Mitzva of Eating Matza: matza made from Bikkurim and Second Tithe

תנו רבנן:

The Sages taught in another baraita:

R' Yosei HaGelili: matza made from bikkurim is invalid by derivation from Exodus 12:20

R' Yosei HaGelili states that the verse “In all of your habitations you shall eat matzot” excludes matza made from first fruits (=bikkurim), since such produce may be eaten only in Jerusalem and not in “all habitations”8.

יכול יוצא אדם ידי חובתו בבכורים?

תלמוד לומר: ״בכל מושבותיכם תאכלו מצות״ —

מצה הנאכלת בכל מושבותיכם,

יצאו בכורים

שאין נאכלין בכל מושבותיכם, אלא בירושלים,

דברי רבי יוסי הגלילי

I might have thought that one can fulfill his obligation by eating matza prepared from the wheat of first fruits;

therefore, the verse states: “In all of your habitations you shall eat matzot” (Exodus 12:20).

This verse indicates that one fulfills his obligation only with matza that may be eaten “in all of your habitations.”

This expression excludes first fruits,

which may not be eaten in all of your habitations, but only in Jerusalem.

This is the statement of R' Yosei HaGelili.

R' Akiva: matza made from bikkurim is Invalid by Analogy to Bitter Herbs; but Second Tithe matzah is valid

R' Akiva gives an alternate homiletic derivation for first fruits being invalid for use as matza: by analogy to bitter herbs (מרור - “maror”).

Since bitter herbs are not among the species eligible as first fruits, by homiletic analogy, first fruits are invalid for use as matza.

However, to prevent over-restriction—excluding wheat and barley due to their eligibility as first fruits—the repetition of “matzot” in the Torah serves to include them.9

רבי עקיבא אומר:

מצה ומרור;

מה מרור שאינו בכורים,

אף מצה שאינה בכורים.

אי:

מה מרור -- שאין במינו בכורים,

אף מצה -- שאין במינה בכורים

אוציא חיטין ושעורין -- שיש במינן ביכורים.

תלמוד לומר: ״מצות״ ״מצות״ ריבה.

[...]

R' Akiva says:

That verse is not the source for this halakha; rather, the fact that one cannot fulfill his obligation with matza of first fruits is derived from the juxtaposition of matza and bitter herbs:

Just as bitter herbs are not first fruits, as they are not included in the seven species to which the mitzva of first fruits applies,

so too matza may not be from first fruits.

If you will claim:

Just as bitter herbs are from a species that are not brought as first fruits,

so too matza must be prepared from a species that are not brought as first fruits, e.g., spelt,

I would then think this comparison excludes wheat and barley, which are from a species that are brought as first fruits and should therefore not be used for the mitzva of matza.

Therefore, the verse states: “Matzot,” “matzot” (Deuteronomy 16:3, 8) to amplify and teach that any matza is acceptable for this mitzva.

[...]

Anonymous baraita: matza made from bikkurim is invalid by derivation from Exodus 12:20; But Second Tithe matzah is valid, derived from the Biblical repetition of “matzot”

An anonymous baraita states that matza made from bikkurim is invalid by derivation from Exodus 12:20 ( the same law and derivation as R’ Yosei in the previous section).

But Second Tithe matzah is valid, derived from the repetition of “matzot” in the Torah serving to include them (the same law and derivation as R’ Akiva in the previous section).

תניא:

יכול יצא אדם ידי חובתו בביכורים,

תלמוד לומר: ״בכל מושבתיכם תאכלו מצות״ —

מצה הנאכלת בכל מושבות,

יצאו ביכורים

שאינן נאכלין בכל מושבות, אלא בירושלים.

יכול שאני מוציא אף מעשר שני?

תלמוד לומר: ״מצות״ ״מצות״ ריבה.

[...]

As it was taught in a baraita:

I might have thought that a person can fulfill his obligation with matza from first fruit;

therefore the verse states: “In all of your habitations you shall eat matzot” (Exodus 12:20).

The verse indicates that one can fulfill his obligation with matza that may be eaten in all habitations.

It excludes first fruits,

which may not be eaten in all habitations, but only in Jerusalem.

I might have thought that I should also exclude second-tithe produce as fit for matza;

therefore the verse states: “Matzot,” “matzot.” As stated above, this repetition serves to amplify, and it includes second tithe in the materials that may be used in the preparation of matza.

[...]

Appendix (Interlude) 1 - Table Summarizing Part 1- summarizing the halakhic rulings and debates so far, around what kinds of matza are valid for fulfilling the mitzva on Passover, based on the sugya

Appendix (Interlude) 2 - “And he didn’t say anything”

“I asked all my teachers, but they didn’t tell me anything“ (Bava Metzia 114a)

The Talmud cites a letter (אגרתיה) sent by Ravin from Eretz Yisrael, where he recounts that he asked “all his teachers (רבותי)” a specific question but received no answer (לא אמרו לי דבר).

However (ברם), there was a question concerning a similar matter that he heard them discuss:10

תא שמע,

דשלח רבין באגרתיה:

דבר זה שאלתי לכל רבותי,

ולא אמרו לי דבר.

ברם, כך היתה שאלה:

[…]

Come and hear a proof,

as Ravin sent a message in his letter from Eretz Yisrael:

I asked all my teachers concerning this matter,

but they did not tell me anything.

But there was this question concerning a similar matter that I heard them discuss:

[…]

“I asked all my teachers, but they didn’t tell me anything“ (Bava Batra 127a)

in the context of a discussion about a specific question regarding the halachic laws of firstborns,11 Rav Pappa questions Rava’s position, citing a message from Ravin (sent from Eretz Yisrael) reporting that he had asked “all my teachers” but received no answer (לא אמרו לי דבר); he eventually heard a teaching from R' Yannai.

אמר ליה רב פפא לרבא:

והא שלח רבין:

דבר זה שאלתי לכל רבותי

ולא אמרו לי דבר,

ברם, כך אמרו משום רבי ינאי:

[…]

Rav Pappa subsequently said to Rava:

But didn’t Ravin send a letter from Eretz Yisrael to Babylonia, stating:

I asked all my teachers about this matter

and they did not tell me anything;

but this is what they said in the name of R’ Yannai:

[…]

Upon hearing this, Rava publicly retracts his prior teaching. He appoints an amora (announcer) to declare: “What I previously taught was mistaken. The correct version is as said in R' Yannai’s name”.12

הדר אוקי רבא אמורא עליה,

ודרש:

דברים שאמרתי לכם – טעות הן בידי,

ברם, כך אמרו משום רבי ינאי:

[…]

Rava then established an amora to repeat his lesson to the masses aloud

and taught:

The statements that I said to you are a mistake on my part.

But this is what they said in the name of R’ Yannai:

[…]

Tacit Approval or Unaware? Tefillin Straps, Colored Wool, and the Limits of Inference from Silence (Menachot 35a)

A baraita states that R’ Yehuda recounts stories of prominent rabbis not protesting the usage of techelet and purple straps on tefillin (showing that it must be permitted).

The baraita in both cases says that other sages responded to R’ Yehuda by saying that the silence of these prominent rabbis stemmed simply from ignorance of the acts (those their consent is these cases cannot be inferred).

Both are cases of prominent sages—R’ Akiva and R’ Eliezer ben Hyrcanus—who did not object when close associates tied their tefillin with colored wool instead of the halakhically standard leather:

A Student of R’ Akiva used sky-blue (tekhelet) wool for his tefillin straps

R’ Akiva did not rebuke him (לא אמר לו דבר).

R’ Yehuda infers from this that it must be permitted, rhetorically asking: would “that righteous person” (אותו צדיק - i.e R’ Akiva) have witnessed such a deviation and remained silent?

The response: R’ Akiva must have not seen it; had he seen it, he would in fact not have allowed (מניחו) it.

א"ר יהודה:

מעשה בתלמידו של ר"ע

שהיה קושר תפיליו בלשונות של תכלת

ולא אמר לו דבר

איפשר אותו צדיק ראה תלמידו,

ולא מיחה בו?!

אמר לו:

הן

לא ראה אותו

ואם ראה אותו —

לא היה מניחו

R’ Yehuda said:

There was an incident involving a student of R’ Akiva,

who would tie his phylacteries with strips of sky-blue wool rather than hide,

and R’ Akiva did not say anything to him.

Is it possible that that righteous man saw his student doing something improper

and he did not object to his conduct?!

Another Sage said to R’ Yehuda:

Yes, it is possible that the student acted improperly,

as R’ Akiva did not see him,

and if he had seen him,

he would not have allowed him to do so.

Hyrcanus, Son of R’ Eliezer, used purple (argaman) wool for his tefillin straps

In this case as well, no rebuke was issued (showing that it must be permitted). The other Sages respond similarly: R’ Eliezer must have not seen it. If he had, he indeed would have objected.

מעשה בהורקנוס בנו של ר' אליעזר בן הורקנוס

שהיה קושר תפיליו בלשונות של ארגמן

ולא אמר לו דבר

איפשר אותו צדיק ראה בנו,

ולא מיחה בו?!

אמרו לו:

הן

לא ראה אותו

ואם ראה אותו —

לא היה מניחו

The baraita continues: There was an incident involving Hyrcanus, the son of R’ Eliezer ben Hyrcanus,

who would tie his phylacteries with strips of purple wool,

and his father did not say anything to him.

Is it possible that that righteous man saw his son doing something improper

and he did not object to his conduct?!

The Sages said to him:

Yes, it is possible that his son acted improperly,

as R’ Eliezer did not see him,

and if he had seen him,

he would not have allowed him to do so.

Silent Consent: Two Stories Relating to inference from silence of halachic approval (Shabbat 29b)

Story 1: Extending Oil Lamp Burn Time with an Eggshell

R' Yehuda recounts a precedent: during Shabbat at the house of Nitza in Lod, they did a specific act.13 R' Tarfon and other elders present did not object.14

The Rabbis reject this inference. They argue the ruling cannot be generalized from that case, since the “house of Nitza” was composed of vigilant individuals.15

תניא

אמר רבי יהודה:

פעם אחת

שבתנו בעליית בית נתזה בלוד,

[...]

והיה שם רבי טרפון וזקנים,

ולא אמרו לנו דבר.

אמרו לו:

משם ראיה?!

שאני בית נתזה, דזריזין הן.

With regard to the dispute between R' Yehuda and the Rabbis, it was taught in a baraita that

R' Yehuda said to the Rabbis:

One time

we spent our Shabbat in the upper story of the house of Nit’za in the city of Lod

[...]

And R' Tarfon and other Elders were there

and they did not say anything to us. Apparently, there is no prohibition.

The Rabbis said to him:

Do you bring proof from there?!

The legal status of the Elders who were sitting in the house of Nit’za is different. They are vigilant.

Story 2: Dragging a Bench on a Marble Floor

Avin of Tzippori dragged a bench on a marble upper floor in front of R' Yitzḥak ben Elazar, who objected.

R' Yitzḥak ben Elazar explained to Avin why he was making a point in protesting: silence in such cases could eventually lead to leniency in the future by viewers by faulty analogy—just as R' Yehuda misunderstood the silence of the elders at Nitza, leading to “destruction”.16

אבין ציפוראה

גרר ספסלא

בעיליתא דשישא

לעילא מרבי יצחק בן אלעזר.

אמר ליה:

אי שתיקי לך

כדשתיקו ליה חבריא לרבי יהודה

נפיק מיניה חורבא

[...]

The Gemara relates:

Avin from the city of Tzippori

dragged a bench

in an upper story, whose floor was made of marble,

before R' Yitzḥak ben Elazar.

R' Yitzḥak ben Elazar said to him:

If I remain silent and say nothing to you,

as R' Tarfon and the members of the group of Elders were silent and said nothing to R' Yehuda,

damage will result, as it will lead to unfounded leniency in the future.

[...]

The iron sulfate (Kankantom) Controversy: R’ Meir Between R’ Akiva and R’ Yishmael (Eruvin 13a)

A baraita records R' Akiva clarifying that a certain halachic statement17 was not made by R' Yishmael, but rather by an unnamed student—and yet, he says, the halakha follows that student.

תניא,

אמר רבי עקיבא:

לא אמר רבי ישמעאל דבר זה,

אלא אותו תלמיד אמר דבר זה,

והלכה כאותו תלמיד

It was taught in a baraita that

R' Akiva said:

R' Yishmael did not state this matter, as it is unlikely that R' Yishmael would err in this manner;

rather, it was that disciple who stated that matter on his own,

and the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of that disciple.

The Talmud questions the internal contradiction: if the statement is not from R' Yishmael, how can the halakha follow it?

Two resolutions are offered:

Shmuel (via Rav Yehuda): R' Akiva said this only “to sharpen the students' thinking”18

Rav Naḥman bar Yitzḥak: R' Akiva meant that the student’s statement was reasonable, not that it was halachically binding.

הא גופה קשיא:

אמרת ״לא אמר רבי ישמעאל דבר זה״ —

אלמא לית הלכתא כוותיה,

והדר אמרת: ״הלכה כאותו תלמיד״!

אמר רב יהודה, אמר שמואל:

לא אמרה רבי עקיבא אלא לחדד בה התלמידים.

ורב נחמן בר יצחק אמר:

נראין איתמר.

With regard to that baraita the Gemara asks: This baraita itself is difficult.

You stated initially that R' Yishmael did not state this matter;

apparently the halakha is not in accordance with the opinion of the disciple.

And then you said: The halakha is in accordance with the opinion of that disciple.

Rav Yehuda said that Shmuel said:

R' Akiva said that the halakha is in accordance with that disciple only to sharpen the minds of his students with his statement. Seeking to encourage his students to suggest novel opinions, he praised that disciple before them but did not actually rule in accordance with the disciple’s opinion.

And Rav Naḥman bar Yitzḥak said, in another attempt to resolve the contradiction:

The statement of the disciple appears to be reasonable was stated. Although R' Yishmael himself did not make that statement, the statement of the disciple is reasonable.

Identity of the Anonymous Student

R' Yehoshua ben Levi states that this specific three-part transmission formula (“a certain student said in the name of R’ Yishmael in front of R’ Akiva”) always refers to R' Meir, who studied under both R' Yishmael and R' Akiva:

אמר רבי יהושע בן לוי:

כל מקום שאתה מוצא

״משום רבי ישמעאל

אמר תלמיד אחד

לפני רבי עקיבא״ —

אינו אלא רבי מאיר,

ששימש את רבי ישמעאל ואת רבי עקיבא

R' Yehoshua ben Levi said:

Anywhere that you find a statement introduced with:

“said before R' Akiva

a certain disciple

in the name of R' Yishmael”,

it is none other than R' Meir,

who was the student who served both R' Yishmael and R' Akiva.

A baraita cites R' Meir recounting that while he was a student of R' Yishmael, he added iron sulfate19 to the ink he used for writing (sacred texts), and R' Yishmael raised no objection.

However, when he later studied under R' Akiva, R' Akiva forbade the practice.

דתניא,

אמר רבי מאיר:

כשהייתי אצל רבי ישמעאל

הייתי מטיל קנקנתום לתוך הדיו,

ולא אמר לי דבר.

כשבאתי אצל רבי עקיבא,

אסרה עלי

[...]

As it was taught in a baraita that

R' Meir said:

When I was a student with R' Yishmael,

I used to put iron sulfate [kankantom] into the ink with which I wrote Torah scrolls,

and he did not say anything to me.

When I came to study with R' Akiva,

he prohibited me from doing so.

[...]

Iron Sulfate and Scriptural Integrity

Rav Yehuda says the following extended story in the name of Shmuel, quoting R' Meir:

אמר רב יהודה,

אמר שמואל,

משום רבי מאיר:

Rav Yehuda says that

Shmuel said

in the name of R' Meir:

When R' Meir was a student of R' Akiva, he used iron sulfate in his ink, and R' Akiva did not object

When R' Meir was a student of R' Akiva, he used iron sulfate in his ink, and R' Akiva did not object.

כשהייתי לומד אצל רבי עקיבא

הייתי מטיל קנקנתום לתוך הדיו,

ולא אמר לי דבר

When I studied with R' Akiva as his disciple,

I used to put iron sulfate into the ink,

and he did not say anything to me.

When R’ Meir later studied under R' Yishmael, R' Yishmael asked his profession (מלאכתך).

Upon hearing that he was a scribe,20 R' Yishmael warned him to be meticulous (זהיר), stating that:

“Omitting (מחסר) or adding (מייתר) a single letter (אות)” causes “destruction (מחריב) of the entire world (עולם כולו)”.

וכשבאתי אצל רבי ישמעאל,

אמר לי:

בני!

מה מלאכתך?

אמרתי לו: לבלר אני.

אמר לי:

בני!

הוי זהיר במלאכתך,

שמלאכתך מלאכת שמים היא,

שמא אתה מחסר אות אחת

או מייתר אות אחת —

נמצאת:

מחריב את כל העולם כולו

But when I came to study with R' Yishmael,

he said to me:

My son! what is your vocation?

I replied: I am a scribe [lavlar] who writes Torah scrolls.

He said to me:

My son!

be careful in your vocation,

as your vocation is heavenly service,

and care must be taken lest you omit a single letter

or add a single letter out of place,

and you will end up destroying the whole world in its entirety.

R' Meir replied to R' Yishmael that he uses iron sulfate in his scribal ink (which lessens the risk of erasing).

R' Yishmael objects, citing the requirement from the sota ritual of “he shall blot them out” (Numbers 5:23), inferring from there that only ink that can be blotted out can be used (by a scribe for ritual texts).

אמרתי לו:

דבר אחד יש לי

ו׳קנקנתום׳ שמו,

שאני מטיל לתוך הדיו.

אמר לי:

וכי מטילין קנקנתום לתוך הדיו?!

והלא אמרה תורה:

״וכתב ומחה״ --

כתב שיכול למחות.

I said to him:

I have one substance

called iron sulfate,

which I place into the ink, and therefore I am not concerned.

He said to me:

May one place iron sulfate into the ink?!

Didn’t the Torah state with regard to sota:

“And the priest shall write these curses in a book, and he shall blot them out into the water of bitterness” (Numbers 5:23)?

The Torah requires writing that can be blotted out.

Compare also Wikipedia, “Ha Lachma Anya”.

טבל שלא נתקן - tevel.

This passage is a classic example of rabbinic gezerah shavah reasoning combined with phonetic wordplay—a technique that blends legal hermeneutics and linguistic intuitive similarities.

Textual and Linguistic Analysis:

“Leḥem oni” (לחם עוני) in Deut. 16:3 refers to the matza eaten on Passover.

Written with an ‘ayin’ (ע), it means “poor man’s bread.”

Phonetically, it resembles “oni” (אוני) with an ‘alef’ (א), meaning “mourning.”

R. Yosei HaGelili’s Derivation:

He treats the similarity in sound as significant. Despite the different roots and letters, the homophony (oni with ayin vs. alef) enables a legal association.

He references Deut. 26:14, where one confesses not eating second tithe during “oni” (אוני) — acute mourning (אנינות - aninut).

Conclusion: Only matza that can be eaten during aninut (acute mourning) fulfills the Passover obligation.

Second tithe (ma’aser sheni) is disqualified since it must be eaten in joy (שמחה) and is forbidden in mourning (aninut).

Halakhic Implication:

R. Yosei HaGelili rules out second tithe matza as valid for the mitzvah of Passover. Why? Because it’s ritually restricted—only to be consumed in Jerusalem and in a state of joy. Since it’s forbidden during mourning, it doesn’t qualify as leḥem oni.

Pshat Perspective:

This is not a straightforward lexical argument—it’s a midrashic move that hinges on phonetic proximity (עוני vs. אוני) to derive legal exclusion.

Historically, it reflects the rabbinic practice of exploiting multivalent readings (visual/aural) of Torah texts.

From a linguistic standpoint, it demonstrates a flexible, performative relationship to language—where sound can override strict morphology when it serves a halakhic or rhetorical goal.

It's a stretch by modern standards, but entirely within the logic of rabbinic hermeneutic.

From a historical linguistics perspective, the homophony between עוני (oni with ayin) and אוני (oni with alef) reflects the history of Semitic phonology and the evolution of Hebrew script and pronunciation—combined with rabbinic drash:

In Biblical Hebrew, ayin (ע) and alef (א) were phonetically distinct:

Ayin (ע) was a voiced pharyngeal fricative (similar to Arabic ‘ʿayn’).

Aleph (א) was a glottal stop.

But already by the late Second Temple period, and certainly in Mishnaic Hebrew, these distinctions were lost in spoken language. This allowed for plays on words that only worked in pronunciation, not in writing.

So, even though:

עוני = poverty (root ע־נ־י)

אוני = mourning (root א־נ־י)

…they would sound nearly identical to a listener by the early rabbinic period.

לא אמרו לי דבר - “they didn’t say anything (דבר) to me“ - suggesting tacit approval or at least tolerance in practice.

See my appendix for an extended discussion of this Talmudic idiomatic phrase: “Appendix (Interlude) 2 - “And he didn’t say anything”“.

שוין - literally: “[They’re] equal”, an idiom meaning “everyone agrees [regarding halacha X]”.

פושרין - presumably due to the increased risk of rapid leavening.

“due to [becoming] accustomed (הרגל) to [something that may lead to] sin (עבירה)”.

מושבותיכם ; thus, it is invalid for the mitzva of matza on Passover.

The same drash that R’ Akiva used in the earlier section to derive that Second Tithe Matza is valid.

The specific questions under discussion there aren’t relevant for our purposes here.

As an aside, see also ibid. in the subsequent section these notable and unusual tradents:

רבי יעקב משמיה דבר פדא,

ורבי ירמיה משמיה דאילפא אמרי:

R’ Ya’akov in the name of Bar-Padda,

and R’ Yirmeya in the name of Ilfa, each say:

[…]

And ibid., Bava_Metzia.114a.10:

אשכחיה רבה בר אבוה לאליהו

דקאי בבית הקברות של גוים,

אמר ליה:

[…]

The Talmud relates:

Rabba bar Avuh found Elijah

standing in a graveyard of non-Jews.

Rabba bar Avuh said to him:

[…]

The specific questions under discussion there aren’t relevant for our purposes here.

As an aside, see a notable phrase used when starting the subsequent passage in that Talmudic sugya, which begins with a new question sent by the people of Akra de-Agma to Shmuel, asking for a ruling (ילמדנו רבינו - “Teach us, our master“):

שלחו ליה בני אקרא דאגמא לשמואל:

ילמדנו רבינו:

[…]

The residents of Akra De’Agma sent the following inquiry to Shmuel:

Teach us, our master:

[…]

The specific act under discussion there isn’t relevant for our purposes here.

He cites this as proof that such an act is permitted.

It’s notable that here as well, as in the previous cases from elsewhere in the Talmud, it’s R’ Yehuda attempting to prove from stories of silence of sages in stories of precedent, while the consensus anonymous rabbis oppose the legitimacy of generalizing based on the precedent.

In general, many additional examples can be adduced of argument from silence in the Talmud; see especially the many search results of “לא אמרו לי דבר“.

זריזין - who could be trusted not to come to do the melacha, thus, no halachic guardrails were necessary in their specific case; for other, this isn’t the case.

חורבא.

As an aside, see the next section, which is historically interesting:, where “the synagogue head (ריש כנישתא) of Batzra” is said to have dragged a bench before R' Yirmeya the Elder, who objected:

ריש כנישתא דבצרה

גרר ספסלא

לעילא מרבי ירמיה רבה.

אמר ליה:

[...]

On the topic of dragging, the Gemara relates that the Head of the Kenesset of Batzra

dragged a bench

before R' Yirmeya the Great on Shabbat.

R' Yirmeya said to him:

[...]

The specific statement under discussion there isn’t relevant for our purposes here.

לחדד בה התלמידים - literally: “to sharpen the students with it“, i.e. not to indicate the actual halakha.

On this surprising idea, see my extended discussion in my piece on stories of deception in the Talmud, at my Academia page.

קנקנתום.

This term is from Greek, see Jastrow:

(קלקנתום, קלקנתוס, קנ׳

m[asculine]

(κάλκανθος [cf. khálkanthon], calcanthum) vitriol

(also called atramentum sutorum, see: Smith, ’Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities’ under the word),

used as an ingredient of shoe-black, and of ink.

[Mishnah] Gittin 2:3:

ובקנ׳

and with calcanthum (as writing ink)

explained [by the Talmud] ibid. 19a:

חרתא דאושכפי,

see:

אושכפא.

Eruvin 13a:

דבר אחד

…

וק׳ שמו וכ׳

I have an ingredient whose name is calcanthum, which I put into the ink.

Tosefta Shabbat 11:18:

אחד נותן את הדיו

…

הק׳

if one puts in the (dry) ink, another the water, and a third person the calcanthum

and elsewhere.

See Wikipedia, “Chalcanthum“:

In alchemy, chalcanthum, also called chalcanth or calcanthum, was a term used for the compound blue vitriol (CuSO4), and the ink made from it.

The term was also applied to red vitriol (a native sulfate of cobalt), and to green vitriol (ferrous sulfate).

Some maintained calcanthum to be the same thing as colcothar, while others believed it was simply vitriol (sulfuric acid).

Broader analysis:

This passage offers an example of how halakhic reasoning intersects with historical science, especially the practical chemistry of ancient scribes.

1. Substance: קנקנתום (Kankantom / Chalcanthum)

The term is clearly borrowed from Greek (χάλκανθον, chalcanthon), pointing to cultural and technical transmission from Greco-Roman science into rabbinic praxis.

In Greco-Roman antiquity, “chalcanthum” denoted various sulfates, especially copper sulfate (blue vitriol) and iron sulfate (green vitriol). These were standard chemical fixatives that improve ink adhesion and permanence.

See Wikipedia, “Iron(II) sulfate“, section “Historical uses“:

Ferrous sulfate was used in the manufacture of inks, most notably iron gall ink, which was used from the Middle Ages until the end of the 18th century.

Chemical tests made on the Lachish letters (c. 588–586 BCE) showed the possible presence of iron

2. Halakhic Implications

The key halachic tension is between durability and erasability. The ink must:

Be permanent enough for sacred writing (Torah scrolls),

But erasable in cases like the sota ritual, where the curses are written and then blotted into water.

R’ Yishmael holds: use only ink that can be erased—he anchors this to the explicit verse (“וכתב ומחה”).

R’ Akiva appears, at least in one tradition, to allow more chemically stable ink.

3. Historical and Literary Tension:

The sources contradict: did R’ Akiva allow or forbid kankantom? Both traditions are preserved.

That ambiguity might reflect different roles: ink for Torah (permanent) vs. ink for ritual (erasable). The texts blur those boundaries.

R’ Yishmael's apocalyptic warning (a single letter could destroy the world) dramatizes the cosmic weight of textual integrity, underscoring the role of scribes as theological agents, not just technicians.

לבלר - from Latin.