Pt1 Revealing the Order: Literary Structure and Rhetoric in the Mishnah

This is the first part of a three-part series, based on my research on literary structure in the Mishnah.1 The outline of the series is below.

Intro: Beyond the Dense Block of Text

The Mishnah, a foundational text of Rabbinic Judaism, can appear to readers as a formidable challenge. Traditionally, it's often presented as, in my own words from an earlier paper, "a block of dense text," making it difficult for readers to discern the underlying patterns and logical flow.2

This density can obscure the craftsmanship of the Mishnaic editor.

In my ongoing effort to create more accessible, reader-friendly, and structurally-aware versions of Talmudic texts, I've worked on formatting approaches that highlight this underlying literary structure.

The study of Mishnaic structure is particularly interesting because, as I’ve noted, it "shows how the Mishnah used somewhat complex literary structures, considering that the Mishnah was (purportedly) originally an oral work".3

This series aims to analyze these patterns, particularly the use of lists.4

My goal is to demonstrate how visual presentation—breaking down the text into formatted lists and tables—can transform our understanding and appreciation of the Mishnah.

When the structure becomes "much more apparent," the Mishnah’s often complex literary framework becomes more navigable, and its internal logic shines through (Mishnah: Visualizing Literary Structure, p. 1).

By visually presenting these lists, my hope is to help readers discern the Mishnah's often formulaic literary structure more effectively.

This isn't just an aesthetic exercise; it's a method for deeper comprehension, allowing us to see the relationships between items, hierarchies, and categories that the Mishnaic editor carefully constructed.

Outline

Intro

Beyond the Dense Block of Text

The Under-appreciated Role of Lists in Mishnaic Discourse

My Technical Approach to Visualization

Part 1

Foundational Example 1: Hierarchies of Impurity and Sanctity in Tractate Kelim

Case Study: Kelim 1:1-4 – "Hierarchy of Ritual Impurities: 11 Levels of Sources and Methods of Conveyance"

Case Study: Kelim 1:6-9a – "The 10/11 Levels of Holiness in the Land of Israel and the Temple"

Simple Enumeration with Deeper Implications

Case Study: Kelim 2:3 – "Earthen Vessels Not Susceptible to Impurity: A List of 14 Items"

Case Study: Kelim 3:1-2a – "Determining Ritual Purity of Earthen Vessels Based on Size of Holes for Food and Liquids - List of 8"

Concluding Thoughts for Part 1

Part 2: Cataloging Complexity – The Diverse Forms of Mishnaic Lists

Introduction to Part 2: Beyond Simple Lists

Numerical and Range-Based Organization

Case Study: Arakhin 2:1b-6a – "A List of 14 Number Ranges in Temple Services, Purity Laws, and Religious Observances"

Case Study: Arakhin 3:1-5a – "A List of 5 Fixed and Variable Financial Penalties and Costs"

Comparative and Contrastive Lists

Case Study: Eduyot 5:1-4 – "17 Issues Where Beit Shammai is Lenient and Beit Hillel is Strict"

Lists of Actions, Times, and Conditions

Case Study: Megillah 1:1-2 – "Megillah Reading: Possible Dates by City Type and Each of the 7 Days of the Week"

Case Study: Ta'anit 2:2b-4 – "7 Special Prayers for Times of Distress Invoking Biblical Figures for Divine Mercy"

Concluding Thoughts for Part 2

Part 3: Architectural, Procedural, and Thematic Lists – The Mishnah’s World in Order

Introduction to Part 3: Thematic Cohesion and Grand Narratives through Lists

Structuring Sacred Space and Ritual: The Temple Lists

Case Study: Shekalim 6:3 – "The 13 Gates of the Temple Courtyard: Locations, Names, and Functions"

Case Study: Middot (Selections) – Mapping the Temple's Dimensions

Case Study: Tamid (Selections) – Outlining Temple Procedures

Categorical Lists: Defining Legal Boundaries and Consequences

Case Study: Sanhedrin 7:4a – "List of 17 Transgressors Subject to Death By Stoning"

Case Study: Keritot 1:1 – "List of 34/36 Transgressors Subject to Spiritual Excision (Karet)"

Case Study: Nedarim 6:1-7:2 – "Restricted and Permissible Foods in Vows: A Guide to 46 Cases"

Conclusion: The Mishnaic Mind – Ordered, Rhetorical, and Accessible

References

Appendix - The casuistic formulation (case followed by ruling) in the Mishnah

Intro

The Under-appreciated Role of Lists in Mishnaic Discourse

One of the many striking features of Mishnaic discourse is its relatively heavy usage of lists. Why lists? They serve as structured tools for categorization, frameworks for legal comparison, and methods for presenting overviews of a topic.

As I observed in my first piece in the series (Mishnah: Visualizing Literary Structure, p. 1):

Lists in the Mishnah often follow specific patterns, some containing over ten items, which can span entire chapters.

These lists become much more comprehensible when formatted in a reader-friendly way, rather than how they are traditionally presented: as blocks of text, often broken up into separate sections, due to their length, making them challenging for readers to navigate.

The impact of clear formatting is profound. When we break these lists down and format them clearly, their inherent structure becomes immediately visible.

For instance, "tractates like Megillah, Arachin, and Sotah contain chapter-long lists that, when formatted intuitively, reveal a logical progression that is easier to follow" (Mishnah: Visualizing Literary Structure, p. 1).

My Technical Approach to Visualization

Before we dive into specific examples, a brief note on my technical approach, as detailed in my paper: "All formatting, translations, and tables in these examples are mine (some of my translations are based on the default translations found in Sefaria; but have been adjusted)." (Mishnah: Visualizing Literary Structure, p. 6).

Furthermore, "Wherever possible, I formatted using numbered lists. In the translation, I used number symbols instead of number words; and "Sunday, Monday, etc" instead of "Day 1", where relevant." (Mishnah: Visualizing Literary Structure, p. 6). These small changes contribute significantly to the clarity and accessibility of the Mishnaic text, allowing the structure to be seen more clearly.

My aim is to make these lists visually clear and organized for easier reading and comprehension, moving away from the "traditional layout of the Mishnah as a block of dense text" (Mishnah: Visualizing Literary Structure, p. 1).

Part 1

Foundational Example 1: Hierarchies of Impurity and Sanctity in Tractate Kelim

Let's begin with some foundational examples from Tractate Kelim, which deals with ritual purity and impurity.

These Mishnayot demonstrate how lists are used to establish clear hierarchies.

Hierarchy of Ritual Impurities: 11 Levels of Sources and Methods of Conveyance (Kelim 1:1-4)

Here is my formatted table from Mishnah: Visualizing Literary Structure, p. 7:

Original Hebrew text, formatted (p. 7-8):

My translation (p. 9-10):

‘Fathers’ of impurity:

A dead creeping animal (sheretz)

Seminal emission

Someone who has become impure from contact with a corpse (tamei met)

A leper during the days of his purification (metzora bimei sepharo)

The water of purification that is insufficient for sprinkling (mei chatat that is less than the required amount)

These cause impurity to people and vessels through contact and to earthenware vessels through their airspace, but they do not cause impurity through carrying.

Greater than these: (למעלה מהן)

A carcass (neveilah)

Water of purification that is sufficient for sprinkling (mei chatat that is enough for sprinkling)

These cause impurity to people through carrying, which also causes the person's clothes to become impure by contact.

[... and so on for all 11 levels, following my translation on p.9 of the PDF ...]

Most severe of all:

A corpse (met),

which causes impurity by being in the same enclosed space (tumah through a tent), something no other source of impurity can do.

What this formatting immediately clarifies is the hierarchical structure, driven by the recurring Mishnaic formula "למעלה מהן" (lit. "above them," translated by me as "Greater than these").

Each subsequent level introduces a more potent or encompassing form of impurity.

The original Hebrew text, while containing this logic, becomes far more accessible when the progressive steps are visually separated and numbered as I have done.

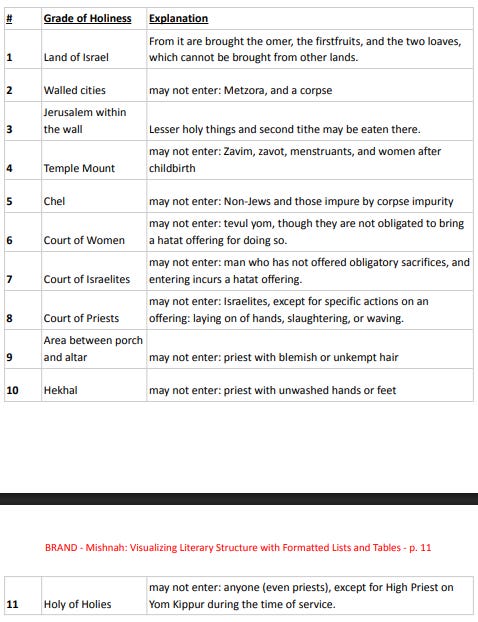

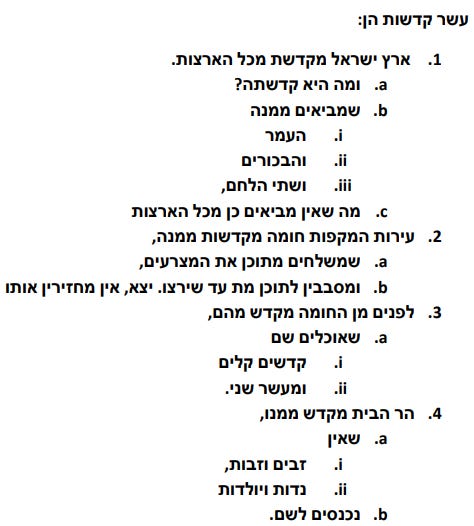

Case Study: Kelim 1:6-9a – "The 10/11 Levels of Holiness in the Land of Israel and the Temple"

Similarly, the Mishnah uses lists to delineate hierarchies of sanctity.

Here is my formatted table and translation for Kelim 1:6-9a (from Mishnah: Visualizing Literary Structure, p. 10-12):

Formula: “X is holier than it, for Y may not enter there”

Visualized in a table:

Original Hebrew text, formatted (p. 11):

My translation:

There are ten levels of holiness:

The Land of Israel is holier than all other lands.

Its holiness is that

i. the omer offering,

ii. the first fruits (bikkurim),

iii. and the two loaves (shtei halechem)

are brought from it,

which are not brought from other lands.

Walled cities are holier than it (i.e. the previous), because:

Metzora’im are sent out of them.

A corpse can be carried around within them until those carrying it are satisfied with the location. Once it is taken out, it cannot be returned.

[... and so on for all 11 levels, following my translation on p.12-13 of the PDF...]

The Holy of Holies is holier than [all of] them, because:

a. Only the High Priest may enter there, and only on Yom Kippur, during the service.

Here, the formula: “X is holier than it [the preceding one], for Y [a specific category of person/impurity] may not enter there” governs the progression.

My table structure, with a dedicated "Explanation" column, makes both the increasing level of sanctity and the corresponding restrictions immediately clear.

This visual organization allows readers to grasp the concentric circles of holiness, moving from the general (Eretz Yisrael) to the most sacred (Holy of Holies), and the rules associated with each zone.

Simple Enumeration with Deeper Implications

Not all Mishnaic lists involve explicit hierarchical formulas.

Some are straightforward enumerations, yet even these often conclude with a general principle that my formatting helps to highlight.

Case Study: Kelim 2:3 – "Earthen Vessels Not Susceptible to Impurity: A List of 14 Items"

Consider this list from Kelim 2:3 (from Mishnah: Visualizing Literary Structure, p. 13-14):

Original Hebrew text, formatted (p. 13-14):

My translation:

[The following] earthenware vessels [are] not susceptible to impurity:

A tray (טבלה - from Latin “tabula”) without a rim (לזבז)

A broken incense-pan (מחתה)

A pierced pan (אבוב) for roasting corn

Drainpipes (סילונות), even if they are bent and have some form of receptacle

A cooking vessel (כבכב) repurposed as a bread-basket cover

A bucket (טפי) used as a cover for grapes

A jar used by swimmers

A small jar attached to the sides of a ladle

A bed

A stool

A bench (ספסל - from Latin)

A table

A boat (ספינה)

A lamp (מנורה) made of earthenware.

These are all pure (ritually unfit to contract impurity).

This is the rule:

Any earthenware vessel that does not have an interior (a defined inner space) —

has no backside (i.e. cannot contract impurity from its exterior)

While a seemingly simple list, the concluding "זה הכלל" (This is the rule) is crucial.

My formatting, by setting this principle apart, emphasizes its role as the unifying legal concept derived from the preceding enumeration.

Case Study: Kelim 3:1-2a – "Determining Ritual Purity of Earthen Vessels Based on Size of Holes for Food and Liquids - List of 8"

Another example of a list leading to varied applications of a measurement principle comes from Kelim 3:1-2a (from Mishnah: Visualizing Literary Structure, p. 14-15).

Here, the list isn't just of items, but of vessel types and their corresponding purity-defining hole sizes.

Formula: “The X -- its measure is Y”.

Visualized in a table:

Original Hebrew text, formatted (p. 15):

My translation:

The minimum size of [the hole in] an earthenware vessel required to become ritually clean:

If it is made for food:

Its size is measured by the volume of olives.

If it is made for liquids:

Its size is measured by the volume of liquids.

If it is made for both food and liquids:

Their size is determined by its primary use, which is olives.

A jar:

R' Shimon says the size is measured by the volume of dried figs.

R' Yehuda says the size is measured by walnuts.

R' Meir says the size is measured by olives.

A large pot and a cooking pot:

Their size is measured by olives.

A jug and a flask:

Their size is measured by the volume of oil.

A small flask:

Its size is measured by the volume of water.

R' Shimon says: The size of all three vessels (on the three items previous: #6-7 - jug, flask, small flask) is measured by seeds.

A lamp:

Its size is measured by the volume of oil.

R' Eliezer says: It is measured by the value of a small perutah coin.

In this Mishnah, the formula "The X vessel -- its [hole's] measure is based on Y” is applied across different types of vessels, sometimes with rabbinic debate on the exact "Y" (e.g., for a Jar).

My tabular presentation makes it easy to compare these applications and see the systematic approach to a seemingly disparate set of objects.

The visual clarity allows the reader to quickly grasp the specific measure for each vessel type, and the underlying principle of using functional hole-size as a determinant of purity.

Concluding Thoughts for Part 1

As these examples from Tractate Kelim demonstrate, the Mishnah is far from a monolithic block of text. It employs clear literary structures, with lists being a primary tool for organization, categorization, and legal definition.

My work in visually reformatting these texts aims to make these structures readily apparent.

By doing so, we not only ease comprehension but also gain a deeper appreciation for the Mishnaic editor’s logical approach to compiling and transmitting tannaitic teachings.

In Part 2, we will explore additional list types, including those based on numerical ranges, comparisons, and specific conditions, further unveiling the intricate blueprint of Mishnaic thought.

As I stated in my paper, "By visually presenting these lists, my goal is to help readers understand the Mishnah's often [formulaic] literary structure more effectively" (Mishnah: Visualizing Literary Structure, p. 1), and I hope these initial examples have begun to illustrate that potential.

Listed at the end of this series, under ‘References’.

For all my research on this topic, including those pieces, see my Academia page, section “Mishnah - Formatted”.

I'll be drawing all my examples case studies from for that series

The full hyperlinked citations and original Hebrew texts can be found there.

See there also for my work on formatting, summarizing, and providing tables on select Mishnah tractates. Currently 4 tractates, plus 4 chapters of tractate Kelim.

“Literary Structure and Rhetorical Technique in the Mishnah: Visualizing Patterns with Formatted Lists and Tables” (from here on I’ll be referring to this piece as: ‘Mishnah: Visualizing Literary Structure’), p. 1.

Mishnah: Visualizing Literary Structure, p. 1.

Whether the Mishnah and Talmud were in fact historically oral works is something that I believe is not fully clear; I hope to return to this topic at some point.

Compare also the formal term ‘enumeration’.

For a good recent scholarly overview of the general topic, see Roman Alexander Barton et. al. (eds.), Forms of List-Making: Epistemic, Literary, and Visual Enumeration (2023).