Pt2 Anecdotes in Berakhot: A Selected Anthology

This is the second and final part of a two-part series. Part 1 is here; the outline of the series can be found at Part 1.

Part 2

Rabban Gamliel recites Shema on his wedding night despite a groom’s exemption - Berakhot 16a (Mishnah 2:5)

Berakhot.16a.8 (= Mishnah_Berakhot.2.5)1

חתן פטור מקריאת שמע לילה הראשונה ועד מוצאי שבת

אם לא עשה מעשה.

ומעשה ברבן גמליאל שנשא אשה

וקרא לילה הראשונה.

אמרו לו תלמידיו: למדתנו רבינו שחתן פטור מקריאת שמע?

אמר להם: איני שומע לכם לבטל הימני מלכות שמים אפילו שעה אחת.

The Mishnah continues: A groom is exempt from the recitation of Shema on the first night of his marriage, which was generally Wednesday night, until Saturday night,

if he has not taken action and consummated the marriage, as he is preoccupied by concerns related to consummation of the marriage.

The Mishnah relates that there was an incident where Rabban Gamliel married a woman

and recited Shema even the first night.

His students said to him: Didn’t our teacher teach us that a groom is exempt from the recitation of Shema?

He answered them: Nevertheless, I am not listening to you to refrain from reciting Shema, and in so doing preclude myself from the acceptance of the yoke of the Kingdom of Heaven, for even one moment.

Anecdotes of Rabban Gamliel - Berakhot 16b (Mishnah 2:6-7)

Berakhot 16b.5 (=Mishnah_Berakhot.2.6-7)

Anecdote #1 - Rabban Gamliel bathes the first night after his wife’s death

רחץ לילה הראשון שמתה אשתו.

אמרו לו תלמידיו: למדתנו רבינו שאבל אסור לרחוץ?

אמר להם:

איני כשאר בני אדם,

אסטניס אני.

The Mishnah relates another episode portraying unusual conduct by Rabban Gamliel.

He bathed on the first night after his wife died.

His students said to him: Have you not taught us, our teacher, that a mourner is prohibited to bathe?

He answered them:

I am not like other people,

I am delicate2

For me, not bathing causes actual physical distress, and even a mourner need not suffer physical distress as part of his mourning.

Anecdote #2 - Rabban Gamliel accepts condolences for his slave Tavi

וכשמת טבי עבדו --

קבל עליו תנחומין.

אמרו לו תלמידיו: למדתנו רבינו שאין מקבלין תנחומין על העבדים?

אמר להם:

אין טבי עבדי כשאר כל העבדים,

כשר היה.

Another exceptional incident is related: And when his slave, Tavi, died --

Rabban Gamliel accepted condolences for his death as one would for a close family member.

His students said to him: Have you not taught us, our teacher, that one does not accept condolences for the death of slaves?

Rabban Gamliel said to his students:

My slave, Tavi, is not like all the rest of the slaves,

he was virtuous (כשר) and it is appropriate to accord him the same respect accorded to a family member.

Rabbi Eliezer’s Students try to console him for a slave’s death; he repeatedly avoids them - Berakhot 16b

תנו רבנן:

עבדים ושפחות —

אין עומדין עליהם בשורה,

ואין אומרים עליהם

ברכת אבלים

ותנחומי אבלים.

The Sages taught in a baraita:

For slaves and female slaves who die —

one does not stand in a row of comforters to console the mourners,

and one recites neither

the blessing of the mourners (ברכת אבלים)

nor the consolation of the mourners (תנחומי אבלים)

מעשה ומתה שפחתו של רבי אליעזר.

נכנסו תלמידיו לנחמו.

An incident is related that when R’ Eliezer’s female slave died,

his students entered to console him.

כיון שראה אותם

עלה לעלייה,

ועלו אחריו.

נכנס לאנפילון,

נכנסו אחריו.

נכנס לטרקלין,

נכנסו אחריו.

When he saw them approaching

he went up to the second floor,

and they went up after him.

He entered the gatehouse [anpilon],

and they entered after him.

He entered the banquet hall (טרקלין)

and they entered after him.

אמר להם:

כמדומה אני שאתם נכוים בפושרים,

עכשיו אי אתם נכוים אפילו בחמי חמין,

Having seen them follow him everywhere, he said to them:

It seems to me3 that you would be burned (נכוים) by lukewarm water (פושרים),

meaning that you could take a hint and when I went up to the second floor, you would understand that I did not wish to receive your consolations.

Now I see that you are not even burned by boiling hot water.

לא כך שניתי לכם:

עבדים ושפחות --

אין עומדים עליהם בשורה,

ואין אומרים עליהם

ברכת אבלים

ולא תנחומי אבלים?

Did I not teach you the following:

For slaves and female slaves who die --

one does not stand in a row of comforters to console the mourners,

and one neither

recites the blessing of the mourners

nor does he recite the consolation of the mourners,

as the relationship between master and slave is not like a familial relationship?

אלא מה אומרים עליהם?

כשם שאומרים לו לאדם על שורו ועל חמורו שמתו —

״המקום ימלא לך חסרונך״,

כך אומרים לו על עבדו ועל שפחתו

״המקום ימלא לך חסרונך״.

Rather, what does one say about them when they die?

Just as we say to a person about his ox or donkey which died:

“May God replenish your loss”

so too do we say for one’s slave or female slave who died:

“May God replenish your loss”

as the connection between a master and his slave is only financial in nature.

Rav Adda bar Ahava, Abaye - Rav Adda tears shaatnez from a woman he assumes is Jewish; she is not and sues him - Berakhot 20a

אמר ליה:

קמאי

הוו קא מסרי נפשייהו אקדושת השם,

אנן

לא מסרינן נפשין אקדושת השם.

Abaye said to Rav Pappa:4

The previous generations

while we

are not as dedicated to the sanctification of God’s name.

כי הא דרב אדא בר אהבה

חזייה לההיא כותית דהות לבישא כרבלתא בשוקא.

Typical of the earlier generations’ commitment, the Talmud relates:

Like this incident involving Rav Adda bar Ahava

who saw a non-Jewish woman7 who was wearing a garment [karbalta] made of a forbidden mixture of wool and linen (=shaatnez) in the marketplace.

סבר דבת ישראל היא --

קם קרעיה מינה.

אגלאי מילתא דכותית היא.

שיימוה בארבע מאה זוזי.

Since he thought that she was Jewish --

he stood and ripped it from her.

It was then divulged that she was a non-Jew

and he was taken to court due to the shame that he caused her, and they assessed the payment for the shame that he caused her at 400 zuz.

אמר לה: מה שמך?

אמרה ליה: מתון.

אמר לה:

מתון —

מתון ארבע מאה זוזי שויא.

Ultimately, Rav Adda said to her: What is your name?

She replied: Matun.

In a play on words, he said to her:

Matun, her name,

plus matun, the Aramaic word for 200,

is worth 400 zuz.

Rabbi Ḥanina ben Dosa confronts a deadly arvad; it dies after biting him - Berakhot 33a

תנו רבנן:

מעשה במקום אחד שהיה ערוד, והיה מזיק את הבריות.

With regard to the praise for one who prays and need not fear even a snake, A baraita states:

There was an incident in one place where an arvad (ערוד) was harming the people.

באו והודיעו לו לרבי חנינא בן דוסא.

אמר להם: הראו לי את חורו!

הראוהו את חורו.

נתן עקבו על פי החור,

יצא ונשכו —

ומת אותו ערוד.

They came and told R’ Ḥanina ben Dosa and asked for his help.

He told them: Show me the hole of the arvad.

They showed him its hole.

He placed his heel over the mouth of the hole

and the arvad came out and bit him,

and the arvad died.

נטלו על כתפו והביאו לבית המדרש.

אמר להם:

ראו בני!

אין ערוד ממית,

אלא החטא ממית.

R’ Ḥanina ben Dosa placed the arvad over his shoulder and brought it to the study hall.

He said to those assembled there: See, my sons!

it is not the arvad that kills a person,

rather transgression kills a person.

The arvad has no power over one who is free of transgression.

באותה שעה אמרו:

אוי לו לאדם שפגע בו ערוד,

ואוי לו לערוד שפגע בו רבי חנינא בן דוסא.

At that moment the Sages said:

Woe unto the person who was attacked by an arvad

and woe unto the arvad that was attacked by R’ Ḥanina ben Dosa.

Anecdotes of Rabbi Eliezer’s Students - One prayer leader prays too long, another too briefly; both are defended by Rabbi Eliezer - Berakhot 34a

Anecdote #1 - There was an incident where one student descended to serve as prayer leader before the ark in the presence of R’ Eliezer, and he was excessively prolonging his prayer

תנו רבנן:

מעשה בתלמיד אחד שירד לפני התיבה בפני רבי אליעזר,

והיה מאריך יותר מדאי.

Continuing on the subject of prayer, A baraita states:

There was an incident where one student descended to serve as prayer leader before the ark9 in the presence of R’ Eliezer,

and he was excessively prolonging his prayer.

אמרו לו תלמידיו: כמה ארכן הוא זה!

אמר להם:

כלום מאריך יותר ממשה רבינו?!

דכתיב ביה: ״את ארבעים היום ואת ארבעים הלילה וגו׳״?!

His students complained and said to him: How long-winded10 he is.

He said to them:

Is this student prolonging his prayer any more than Moses our teacher did?!

As about Moses it is written: “And I prostrated myself before YHWH for the forty days and forty nights that I prostrated myself” (Deuteronomy 9:25).

There is no limit to the duration of a prayer.

Anecdote #2 - There was again an incident where one student descended to serve as prayer leader before the ark in the presence of R’ Eliezer, and he was excessively abbreviating his prayer

שוב מעשה בתלמיד אחד שירד לפני התיבה בפני רבי אליעזר,

והיה מקצר יותר מדאי.

There was again an incident where one student descended to serve as prayer leader before the ark in the presence of R’ Eliezer,

and he was excessively abbreviating11 his prayer.

אמרו לו תלמידיו: כמה קצרן הוא זה!

אמר להם:

כלום מקצר יותר ממשה רבינו?!

דכתיב: ״אל נא רפא נא לה״.

His students protested and said to him: How brief12 is his prayer.

He said to them:

Is he abbreviating his prayer any more than Moses our teacher did?!

As it is written with regard to the prayer Moses recited imploring God to cure Miriam of her tzara’at: “And Moses cried out to YHWH, saying: ‘Please, God, heal her, please’” (Numbers 12:13).

This student’s prayer was certainly no briefer than the few words recited by Moses.

Anecdotes of Ḥanina ben Dosa - Berakhot 34b

Anecdote #1 - Rabbi Ḥanina ben Dosa, Rabban Gamliel - R Ḥanina prays for Rabban Gamliel’s sick son and predicts recovery

תנו רבנן:

מעשה שחלה בנו של רבן גמליאל.

שגר שני תלמידי חכמים אצל רבי חנינא בן דוסא לבקש עליו רחמים.

Having mentioned R’ Ḥanina ben Dosa in our Mishnah, the Talmud proceeds to further praise the efficacy of his prayer: A baraita states:

There was an incident where Rabban Gamliel’s son fell ill.

Rabban Gamliel dispatched two scholars to R’ Ḥanina ben Dosa to pray for mercy and healing on his behalf.

כיון שראה אותם,

עלה לעלייה,

ובקש עליו רחמים.

When R’ Ḥanina ben Dosa saw them approaching,

he went up to the attic on the roof of his house

and prayed for mercy on his behalf.

בירידתו אמר להם:

לכו!

שחלצתו חמה.

אמרו לו: וכי נביא אתה?!

Upon his descent, he said to the messengers:

You may go and return to Rabban Gamliel,

as the fever (חמה) has already left (חלצתו) his son and he has been healed.

The messengers asked him: How do you know? Are you a prophet?!

אמר להן:

לא נביא אנכי

ולא בן נביא אנכי,

אלא כך מקובלני:

אם שגורה תפלתי בפי —

יודע אני שהוא מקובל,

ואם לאו —

יודע אני שהוא מטורף.

He replied to them:

I am neither a prophet

nor son of a prophet (see Amos 7:14),14

but I have received a tradition with regard to this indication:

If my prayer is fluent (שגורה) in my mouth as I recite it and there are no errors,

I know that my prayer is accepted.

And if not,

I know that my prayer is rejected (מטורף).

ישבו וכתבו וכוונו אותה שעה.

וכשבאו אצל רבן גמליאל,

אמר להן:

העבודה!

לא חסרתם ולא הותרתם,

אלא כך היה מעשה:

באותה שעה חלצתו חמה

ושאל לנו מים לשתות.

The Talmud relates that these messengers sat and wrote and approximated (כוונו) that precise moment when R’ Ḥanina ben Dosa told them this.

When they came before Rabban Gamliel and related all that had happened and showed him what they had written,

Rabban Gamliel said to them:

I swear by the Temple service (העבודה) that

in the time you wrote you were neither earlier or later;

Rather, this is how the event transpired:

Precisely at that moment his fever broke

and he asked us for water to drink.

Anecdote #2 - Rabbi Ḥanina ben Dosa, Rabbi Yoḥanan ben Zakkai - R Ḥanina heals R Yoḥanan’s son; R Yoḥanan explains why his own prayer is less effective

ושוב מעשה ברבי חנינא בן דוסא

שהלך ללמוד תורה אצל רבי יוחנן בן זכאי,

And there was another incident involving R’ Ḥanina ben Dosa,

who went to study Torah before R’ Yoḥanan ben Zakkai,

וחלה בנו של רבי יוחנן בן זכאי.

אמר לו:

חנינא בני!

בקש עליו רחמים ויחיה.

and R’ Yoḥanan’s son fell ill.

He said to him:

Ḥanina, my son!

pray for mercy on behalf of my son so that he will live.

הניח ראשו בין ברכיו

ובקש עליו רחמים,

וחיה.

אמר רבי יוחנן בן זכאי:

אלמלי הטיח בן זכאי את ראשו בין ברכיו כל היום כולו —

לא היו משגיחים עליו.

R’ Ḥanina ben Dosa placed his head between his knees in order to meditate

and prayed for mercy upon his behalf,

and R’ Yoḥanan ben Zakkai’s son lived.

R’ Yoḥanan ben Zakkai said about himself:

Had ben Zakkai stuck his head between his knees throughout the entire day —

they would have paid him no attention (משגיחים).

אמרה לו אשתו: וכי חנינא גדול ממך?!

אמר לה:

לאו,

אלא

הוא

דומה כעבד לפני המלך,

ואני

דומה כשר לפני המלך.

His wife said to him: And is Ḥanina greater than you?!

He replied to her:

No,

but his prayer is better received than my own because

he

is like a servant before the King,

and as such he is able to enter before the King and make various requests at all times.

I, on the other hand,

am like a minister before the King,

and I can enter only when invited and can make requests only with regard to especially significant matters.

Note the parallel literary structure of the following three stories of Rabban Gamliel in Mishnah Berakhot 2:5-7:

Literary triptych of case stories: Three tightly framed anecdotes placed in sequence, forming a structured set.

Fixed dialogue template:

Action by Rabban Gamliel → anonymous “students” cite a taught norm → Rabban Gamliel answers.Systematic variation in resolution:

Personal exception (body): bathing in mourning → “I am delicate ( אסטניס )”.

Personal exception (relationship/morality): accepting condolences for a slave → “he was virtuous ( כשר )“.

Norm override (principle): reciting Shema despite exemption → refusal to suspend “the yoke of the Kingdom of Heaven ( קבלת עול מלכות שמים )”.

Escalation of stakes: moves from comfort (רחיצה), to social-ritual boundaries (תנחומין על עבדים), to core religious obligation (קריאת שמע).

Reversal symmetry:

First two cases: Rabban Gamliel permits himself what the rule forbids, via exception.

Third case: Rabban Gamliel imposes on himself what the rule permits, via principle.

Authority reinforced, not undermined: students deploy his teachings; Rabban Gamliel clarifies their scope and hierarchy.

Didactic synthesis: Halakhic norms define baselines; individual circumstance and overarching values can legitimately narrow or intensify obligation.

Net effect: a deliberately patterned triptych that teaches not laxity, but calibrated halakhic judgment—rules, exceptions, and value-driven stringency arranged in ascending conceptual order.

istenis - from Greek.

כמדומה אני - an idiom, in our context meaning, “I would have thought/expected/hoped”.

For the context, see the section immediately before, Berakhot.20a.4:

אמר ליה רב פפא לאביי:

מאי שנא ראשונים

דאתרחיש להו ניסא,

ומאי שנא אנן

דלא מתרחיש לן ניסא?

Rav Pappa said to Abaye:

What is different about the earlier generations,

for whom miracles occurred

and what is different about us,

for whom miracles do not occur?

Rav Pappa then goes on to argue that this is especially puzzling, being that their own generation was in fact spiritually superior to previous generations. His arguments are paralleled elsewhere in the Talmud, see my “Pt2 From Desperation to Downpour: Talmudic Stories of Rainmaking (Taanit 24a-b)“, section “Rabba’s Reflection on Generational Spiritual Efficacy: Torah Knowledge vs. Divine Favor“, where I summarize:

The Talmud recounts that Rabba decreed a fast and prayed for rain, but it did not come. People contrasted him with Rav Yehuda, who had been able to bring rain through his prayers.

Rabba responded by noting that while his generation was more knowledgeable in Torah study, learning all six orders of the Mishna (שיתא סדרין), unlike Rav Yehuda’s generation, they were still not successful in bringing rain.

Rabba continued, pointing out that despite their advanced learning, their prayers were ineffective, whereas Rav Yehuda’s simple act of removing a shoe in distress would immediately bring rain.

Rabba suggested that the difference might be due to the people’s unworthiness, not the leaders’ shortcomings, implying that the spiritual state of the generation affects the efficacy of prayers.

On the general trope of declinism in the Talmud, compare these other pieces of mine:

“From Broad Doorways to Needle’s Eye: Generational Decline in Wisdom According to the Talmud (Eruvin 53a)“, especially section “Generational Decline in Wisdom“, and see my note there

“Ancient Burial Caves, Rankings of Beauty, and the Magus: Tales of R’ Bena’a (Bava Batra 58a)“, section “Ranking the Beauty of Sarah, Eve, Adam, Shekhinah, Rav Kahana, Rav, R’ Abbahu, and Jacob“, and see my extended note there.

Two—part series, “The End of an Era: The Mishnah on Societal Decline and the Discontinuation of Rituals (Mishnah Sotah 9:9-15)”, final part here, and see my intro and initial note there.

מסרי נפשייהו - literally: “gave their souls”, i.e. self-sacrifice.

קדושת השם - Kiddush Hashem.

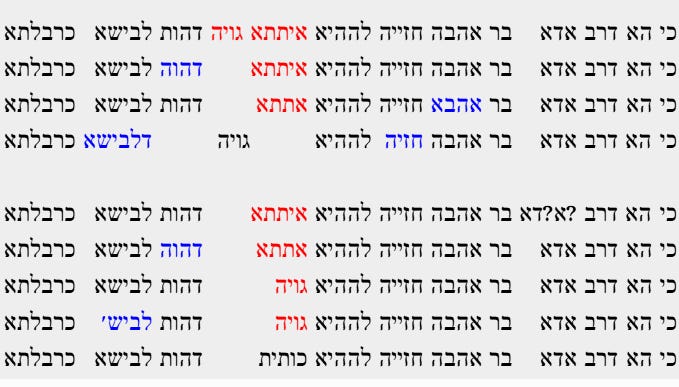

The printed edition here has kutit (כותית ), due to the censor. Manuscripts have either goya (גויה), or simply “woman”, see the manuscript versions of this passage at Al-HaTorah (the last line is the Vilna printed edition):

Note that from a literary structure perspective, these anecdotes are clearly mirroring:

Paired anecdotes (literary diptych): Two nearly identical narratives placed back-to-back.

Symmetry with inversion:

Case A: prayer too long → complaint → rebuttal.

Case B: prayer too short → complaint → rebuttal.

Fixed roles: anonymous “student” (actor), anonymous “students” (chorus/critics), R’ Eliezer (authoritative interpreter).

Scriptural anchoring: each rebuttal cites Moses, but with opposite biblical prooftexts—one maximal (“40 days”), one minimal (“Please, God, heal her, please’”).

Rhetorical function: reframes a quantitative judgment (length) into a normative spectrum validated by precedent.

Punchline logic: extremes are legitimized; criticism collapses when both poles are canonically exemplified.

The net effect is a tight, mirrored construction that teaches tolerance of divergent prayer styles by enclosing them within a single authoritative frame.

ירד לפני התיבה - “descended before the ark”, the common Talmudic idiom for serving as prayer leader.

ארכן - literally: “a lengthener, one who lengthens”.

מקצר - literally: “shortening”.

קצרן - literally: “a shortener, one who shortens”.

Literary structure of these anecdotes of Ḥanina ben Dosa:

Paired miracle narratives (doublet): Two stories explicitly linked (ושוב מעשה), forming a matched set.

Shared core plot: illness → request for intercessory prayer → Ḥanina ben Dosa prays → recovery.

Variation by frame, not outcome:

Story A: emissaries + time-verification.

Story B: direct request + hierarchical metaphor.

Recognition scene in both stories, rhetorical astonishment:

A: “Are you a prophet?!” → epistemic clarification.

B: “Is Ḥanina greater than you?!” → social clarification.

Non-prophetic authority claim: Ḥanina explicitly rejects prophecy; efficacy is diagnosed post hoc by prayer fluency.

External corroboration:

Story A uniquely adds chronometric confirmation (they write down the hour; Rabban Gamliel verifies).

Metaphorical closure:

Story B ends with a court metaphor (servant/slave vs minister) to explain differential access, not personal greatness.

Consistent thesis across both: efficacy of prayer derives from relational posture toward God, not rank, learning, or office.

Rhetorical progression:

A explains how Rabbi Ḥanina knows his prayer worked.

B explains why his prayer works better than that of greater authorities.

Net effect: a carefully paired doublet that normalizes miracle without prophecy, relocates religious power from status to intimacy, and uses two different explanatory registers—empirical timing and social metaphor—to converge on the same claim.

This idiom is found in a number of places in the Talmud, see search results here.

For example, see in the context of a similar story to the one here, in my “Pt3 “Endless Water”: Eight Stories of Uncertain Drowning of a Husband in the Context of Remarriage (Yevamot 121a-b)“, section “Story of the daughter of Neḥunya the Well Digger, who fell into the Great Cistern, her safety prophesied by R’ Ḥanina ben Dosa“, where I summarize:

In this story, set in the 1st century, the daughter of Neḥunya the Well Digger fell into the Great Cistern (בור הגדול). The community approached R’ Ḥanina ben Dosa (a prominent miracle-worker, who lived at the end of the Second Temple period) to pray for her rescue. R’ Ḥanina assured them at various intervals—after the first, second, and third hours—that the girl was safe and ultimately, that she had been rescued from the cistern.

When the girl met R’ Ḥanina, she explained that a ram, led by an old man, had miraculously come to her aid and pulled her out of the cistern.

Amazed by R’ Ḥanina ben Dosa’s prescience, the people questioned whether he was a prophet. He denied being a prophet, instead explaining his confidence as a logical deduction from the righteousness of her father’s work, which involved digging wells for public use. He reasoned that it was unlikely that Neḥunya’s own daughter would perish in a situation related to his life-saving work.