From Legal Procedure to Aggadic Pathos, Calendrical Courts to Emotional Self-Sacrifice: The Narrative Arc of a Talmudic Sugya (Sanhedrin 10b-11a)

Appendix - Making Talmud More Accessible with modern formatting, tables, and AI: A Case Study

This sugya offers a remarkable window into the intersection of law, ethics, and spiritual recognition. It opens with a halakhic debate about the number of judges required to intercalate the Hebrew calendar—a seemingly technical question grounded in biblical precedent—before pivoting to a series of narratives that explore moral courage, humility, and the limits of communal shame.

Figures like Rabban Gamliel, Shmuel the Small (“HaKatan”), and R' Meir are shown not only applying the law but also enacting deep ethical responsibility, sometimes at personal cost, to shield others from embarrassment.

The passage culminates in stories of divine approval—heavenly voices (bat kol) recognizing the spiritual greatness of Hillel and the aforementioned Shmuel the Small—even worthy prophecy (limited only by the fact that their generations were unworthy of it).

What begins as a legal discussion about calendrical procedure thus unfolds into a meditation on moral leadership, human dignity, and the tragic cost of collective failure.

The structure of the sugya reflects this movement: from halakhic precision to aggadic pathos, from judicial procedure to divine voice.

This piece offers a thematic and structural analysis of the sugya, demonstrating the coherence between its legal and narrative components, and exploring how modern formatting, tables, and AI tools can illuminate the underlying architecture and narrative dynamics of such intricate sugyot.

Intercalation of the Hebrew Calendar

See Hebrew Wikipedia, עיבור השנה, my translation:

In Jewish law, the intercalation of the year (עיבור השנה) refers to the designation of a leap year every few years, during which an additional month, Adar I, is added. The Hebrew calendar is based on the lunar cycle, and intercalation is intended to align it with the solar cycle, which governs the seasons.

A year with 13 months is called [in Hebrew] a " ‘pregnant’ year," metaphorically likened to a pregnant woman (אישה מעוברת, "a woman who is pregnant"). A non-leap year is referred to as a "regular/simple year" (שנה פשוטה).

Similar to the Sanctification of the New Moon,1 in the time of the talmudic sages (חז"ל), the Sanhedrin would decide each year whether to declare it a leap year, based on various considerations.

Today, however, the Hebrew calendar follows a fixed system, in which leap years are predetermined according to a 19-year cycle (=Metonic cycle), with 7 leap years occurring within each cycle. In this fixed calendar, a leap year consists of 383 to 385 days.

Jewish law explains that the reason for intercalating the year is the requirement to celebrate Passover in the spring. The talmudic rabbis interpreted the verse "Observe the month of Aviv and perform the Passover for YHWH" (Deuteronomy 16:1) to mean that the month of Nisan must always fall in the spring (Rosh Hashanah 21a). Consequently, they established the practice of intercalating the year approximately every three years.

The changing of the seasons results from the Earth's orbit around the sun, with one complete orbit referred to in astronomy as a tropical year. A tropical year lasts approximately 365¼ days (more precisely: 365.2422 days), whereas 12 lunar cycles amount to roughly 354⅓ days (more precisely: 354.36713 days).

As a result, a tropical year is about 11 days longer than 12 lunar months. If the Hebrew calendar followed only 12 lunar cycles per year, Passover would gradually shift toward winter. To prevent this, a leap year with 13 months is designated whenever the discrepancy accumulates to approximately a full lunar cycle.

Outline

Intro

Intercalation of the Hebrew Calendar

Outline

The Passage

Selection of Judges: The Structure and Meaning of the 3, 5, and 7 Judges

Correspondence of Judicial Numbers to Biblical Verses: Dispute Over the Basis of the Numbers

Connection to the Priestly Benediction (Numbers 6:24-26) or to Royal Officials (II Kings 25:18-19; Jeremiah 52:25)

Rav Yosef’s Baraita and His Readiness to Share Knowledge

Stories of Emotional Self-Sacrifice to Protect Others From Embarrassment

Rabban Gamliel’s Incident in Intercalating the Year: Rabban Gamliel's Request for a Select Group; An Unexpected Eighth Participant; Shmuel the Small Takes Responsibility; Rabban Gamliel's Praise and the Halakhic Limitation

A Gesture to Prevent Embarrassment; R' Ḥiyya and the Garlic Incident

R' Meir’s Precedent: The Story of the Anonymous Betrothal by Intercourse and the Collective Granting of Divorces

Continuing to Trace the Origin of the Practice of Emotional Self-Sacrifice to Protect Others From Embarrassment: The Case of Shecaniah ben Jehiel (Ezra 10:2, 18–44)

God's Refusal to Directly Expose Sinners (Joshua 7:10-11; Exodus 16:28)

Prophetic Warnings and National Ruin: Shmuel the Small, Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel, R’ Yishmael the High Priest, and the Unmourned Death of Yehuda ben Bava

Shmuel the Small, Hillel, and the Echoes of Prophecy

The Case of Shmuel the Small: Prophetic Potential Denied by an Unworthy Generation

Shmuel the Small’s Deathbed Prophecy of National Tragedy: Execution of Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel, R’ Yishmael the High Priest, and Other Rabbis, Plunder of the People, and Looming Global Calamity

Yehuda ben Bava’s Missed Eulogy due to his execution by the Romans

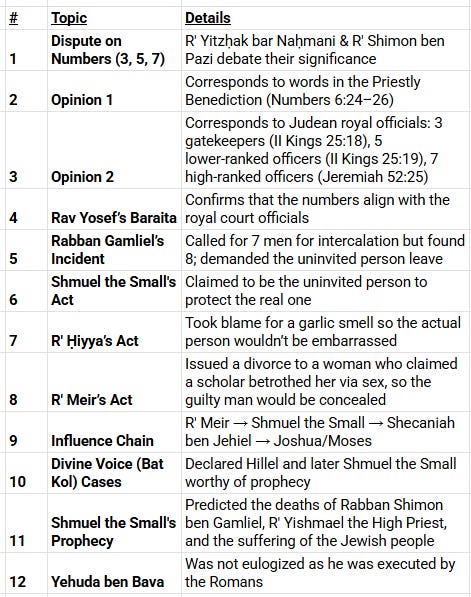

Appendix 1 - Overview Table of Main Stages in the Sugya

Appendix 2 - List of People in the ‘Return to Zion’ Period Who Had Taken Foreign Wives (Ezra 10:18-44)

Members of the priestly clans of Immer, Harim, and Pashhur

Priests

Immer

Harim

Pashhur

Members of the Levite clans (Jozabad, Shimei, and Eliezer), Singers (Eliashib), and Gatekeepers (Shallum, Telem, and Uri)

Levites

Singers

Gatekeepers

Members of the Israelite clans: Parosh, Elam, Zattu, Bebai, Bani, Pahath-moab, Harim, Benjamin, Hashum, and Nebo

Parosh

Elam

Zattu

Bebai

Bani

Pahath-moab

Harim

Hashum

Bani (2)

Nebo

Children from These Marriages

Appendix 3 - Making Talmudic Aggadah More Accessible with AI: A Case Study

Breaking Down a Talmudic Sugya: The Need for Structure

Summarization: Making Implicit Structure Explicit

Visualization: Seeing the Structure Clearly

Contextualizing with an Introduction

Using AI to Make Talmud More Accessible

Conclusion

The Passage

Selection of Judges: The Structure and Meaning of the 3, 5, and 7 Judges

The verses in II Kings 25:18-19 discuss the captives taken by Nebu-chad-nezzar’s “chief of the guards” (רב טבחים) Nebu-zar-adan after Jerusalem's fall in 587 BCE:

Nebuzaradan rounded up prominent Judean religious figures including Seraiah (שריה) the High Priest (כהן הראש), Zephaniah (צפניהו) the Deputy Priest (כהן משנה), and 3 gatekeepers.2

He also took a eunuch (סריס) who had been the commander (פקיד) of the Judean forces (אנשי המלחמה), along with 5 of the high-ranking courtiers known for serving “in the king’s presence” (ראי פני המלך).

In addition, he seized the Judean army scribe (ספר שר הצבא) who had been responsible for gathering3 the common people (עם הארץ) for military service, and 60 commoners (עם הארץ) from the population remaining in Jerusalem.

ויקח רב טבחים:

את שריה, כהן הראש

ואת צפניהו, כהן משנה

ואת שלשת שמרי הסף

ומן העיר לקח:

סריס אחד,

אשר הוא פקיד על אנשי המלחמה

וחמשה אנשים מראי פני המלך,

אשר נמצאו בעיר

ואת הספר שר הצבא,

המצבא את עם הארץ

וששים איש מעם הארץ,

הנמצאים בעיר

The chief of the guards also took:

Seraiah, the chief priest,

Zephaniah, the deputy priest,

and the 3 guardians of the threshold.

And from the city he took:

a eunuch

who was in command of the soldiers;

5 of the royal privy councillors

who were present in the city;

the scribe of the army commander,

who was in charge of mustering the people of the land;

and 60 of the common people

who were inside the city.

Correspondence of Judicial Numbers to Biblical Verses: Dispute Over the Basis of the Numbers

The Talmud questions why the intercalation process requires 3, 5, and 7 men.

A disagreement arises between R' Yitzḥak bar Naḥmani and R' Shimon ben Pazi regarding the reasoning behind these numbers.

הני

שלשה

חמשה

ושבעה,

כנגד מי?

פליגי בה רבי יצחק בר נחמני וחד דעימיה,

ומנו? רבי שמעון בן פזי.

ואמרי לה: רבי שמעון בן פזי וחד דעימיה,

ומנו? רבי יצחק בר נחמני.

The Gemara asks: Corresponding to what was it determined that the intercalation procedure should incorporate these numbers of

three,

five,

and seven judges?

R' Yitzḥak bar Naḥmani and one other Sage who was with him disagree about this.

And who is that other scholar? R' Shimon ben Pazi.

And some say that this was a matter of dispute between R' Shimon ben Pazi and one other scholar who was with him.

And who is that other scholar? R' Yitzḥak bar Naḥmani.

Connection to the Priestly Benediction (Numbers 6:24-26) or to Royal Officials (II Kings 25:18-19; Jeremiah 52:25)

One opinion states that these numbers correspond to the number of Hebrew words in each of the 3 verses of the Priestly Blessing (Numbers 6:24–26).

The other opinion links the numbers to biblical royal appointments:4

3: corresponds to the 3 “gatekeepers” (שומרי הסף - in II Kings 25:18)

5: to the 5 officers who “see the king’s face” (רואי פני המלך - in II Kings 25:19)

7: to the 7 officers ““see the king’s face” (in Jeremiah 52:25)

חד אמר:

כנגד

ברכת כהנים,

וחד אמר:

שלשה – כנגד שומרי הסף,

חמשה – מרואי פני המלך,

שבעה – רואי פני המלך.

One said:

These numbers correspond to

the number of Hebrew words in each of the three verses of the priestly benediction (see Numbers 6:24–26).

And one said:

Three corresponds to the three guards of the door (see II Kings 25:18),

five corresponds to five of the officers who saw the king’s face (see II Kings 25:19),

and seven corresponds to seven officers who saw the king’s face (see Jeremiah 52:25).

Since these numbers represent appointments of distinction, the rabbis saw fit to employ them in the composition of the court as well.

Rav Yosef’s Baraita and His Readiness to Share Knowledge

Rav Yosef cites a baraita affirming that these numbers derive from positions of distinction in the royal court: 3 guards, 5 officers who saw the king’s face, and 7 higher-ranking officers.

Abaye questions why Rav Yosef had not explained this earlier, to which he responds that he hadn't realized they needed (צריכיתו) the information.

Rav Yosef emphasized his willingness to share knowledge, rhetorically asking if they had ever requested something from him that he hadn't provided: “Have you [ever] asked (בעיתו) me something and I did not tell you?!”5

תני רב יוסף:

הני שלשה וחמשה ושבעה:

שלשה – כנגד שומרי הסף,

חמשה – מרואי פני המלך,

שבעה – רואי פני המלך.

אמר ליה אביי לרב יוסף:

עד האידנא

מאי טעמא לא פריש לן מר הכי?!

אמר להו:

לא הוה ידענא דצריכיתו.

מי בעיתו מנאי מילתא ולא אמרי לכו?!

Similarly, Rav Yosef taught a baraita:

These numbers: Three, five, and seven members of the court for intercalation, are adopted from different numbers of the king’s servants.

Three corresponds to: Guards of the door;

five corresponds to: Of those officers who saw the king’s face, mentioned in the book of II Kings;

and seven corresponds to: Officers who saw the king’s face, mentioned in the book of Jeremiah.

When Rav Yosef taught this, Abaye said to Rav Yosef:

until now

What is the reason that the Master did not explain the matter to us this way, although you have taught this material before?!

Rav Yosef said to Abaye and the others with him:

I did not know that you needed this information, as I thought that you were already familiar with the baraita.

Have you ever asked me something and I did not tell you?!

Stories of Emotional Self-Sacrifice to Protect Others From Embarrassment

The process of intercalation (מעברין) of the Hebrew calendar (see my intro on this) required specifically invited (מזומנין) judges.

תנו רבנן:

אין מעברין את השנה אלא

במזומנין לה.

The Sages taught in a baraita:

The year may be intercalated only

by those who were invited by the Nasi, the president of the Great Sanhedrin, for that purpose.

Rabban Gamliel’s Incident in Intercalating the Year: Rabban Gamliel's Request for a Select Group; An Unexpected Eighth Participant; Shmuel the Small Takes Responsibility; Rabban Gamliel's Praise and the Halakhic Limitation

Rabban Gamliel6 instructed that seven Sages be brought early the next morning to a loft (עלייה) to intercalate the year.

Upon arriving, Rabban Gamliel found that eight Sages were present and demanded that the uninvited individual descend immediately (as the number is supposed to be specifically seven, as stated in the earlier section).

Shmuel the Small (שמואל הקטן) stood up, claiming to be the uninvited individual, stating: “I am he who ascended without permission (רשות)”).

Shmuel the Small explained that he had only ascended to observe and “learn the practical halakha” (הלכה למעשה), not to participate in the intercalation.

Rabban Gamliel affirmed Shmuel the Small’s worthiness, stating that (ideally) he should be responsible for intercalating all years. However, the Sages maintained that only those invited could participate.

מעשה ברבן גמליאל

שאמר: השכימו לי שבעה לעלייה.

השכים ומצא שמונה.

אמר:

מי הוא שעלה שלא ברשות?!

ירד!

עמד שמואל הקטן ואמר:

אני הוא שעליתי שלא ברשות,

ולא לעבר השנה עליתי

אלא ללמוד הלכה למעשה הוצרכתי.

אמר לו:

שב בני, שב!

ראויות כל השנים כולן להתעבר על ידך,

אלא אמרו חכמים: אין מעברין את השנה אלא

במזומנין לה.

There was an incident involving Rabban Gamliel,

who said to the Sages: Bring me seven of the Sages early tomorrow morning to the loft designated for convening a court to intercalate the year.

He went to the loft early the next morning and found eight Sages there.

Rabban Gamliel said:

Who is it who ascended to the loft without permission?!

He must descend immediately!

Shmuel HaKatan stood up and said:

I am he who ascended without permission;

and I did not ascend to participate and be one of those to intercalate the year,

but rather I needed to observe in order to learn the practical halakha.

Rabban Gamliel said to him:

Sit, my son, sit!

It would be fitting for all of the years to be intercalated by you, as you are truly worthy.

But the Sages said:

The year may be intercalated only

by those who were invited for that purpose.

A Gesture to Prevent Embarrassment; R' Ḥiyya and the Garlic Incident

The Talmud asserts that in that historical incident, Shmuel the Small was not in fact the uninvited individual:

In fact, Shmuel the Small took the blame to shield the real offender from embarrassment (כיסופא).

The Talmud recounts a similar awkward incident:

R' Yehuda HaNasi was lecturing (דריש), and was disturbed by the smell of garlic.

Not knowing who the offender was, he asked that whoever it was should leave.

R' Ḥiyya exited, prompting all the other attendees to follow him and exit as well.

The next day, R' Shimon, son of R' Yehuda HaNasi, confronted him.

R' Ḥiyya denied being the true culprit, stating “there should not be such behavior among the Jewish people!”7

ולא שמואל הקטן הוה,

אלא איניש אחרינא,

ומחמת כיסופא הוא דעבד.

כי הא דיתיב רבי וקא דריש,

והריח ריח שום.

אמר: מי שאכל שום יצא.

עמד רבי חייא ויצא.

עמדו כולן ויצאו.

בשחר, מצאו רבי שמעון ברבי לרבי חייא.

אמר ליה: אתה הוא שציערת לאבא?!

אמר לו: לא תהא כזאת בישראל!

The Gemara notes: And it was not actually Shmuel HaKatan who had come uninvited,

but another person.

And due to the embarrassment of the other, Shmuel HaKatan did this, so that no one would know who had come uninvited.

The Gemara relates that the story about Shmuel HaKatan is similar to an incident that occurred when R' Yehuda HaNasi was sitting and teaching,

and he smelled the odor of garlic. R' Yehuda HaNasi was very sensitive and could not tolerate this odor.

He said: Whoever ate garlic should leave.

R' Ḥiyya stood up and left.

Out of respect for R' Ḥiyya, all of those in attendance stood up and left.

The next day, in the morning, R' Shimon, son of R' Yehuda HaNasi, found R' Ḥiyya,

and he said to him: Are you the one who disturbed my father by coming to the lecture with the foul smell of garlic?!

R' Ḥiyya said to him: There should not be such behavior among the Jewish people. I would not do such a thing, but I assumed the blame and left so that the one who did so would not be embarrassed.

R' Meir’s Precedent: The Story of the Anonymous Betrothal by Intercourse and the Collective Granting of Divorces

The Talmud states that R' Ḥiyya learned this practice from R' Meir’s precedent:

When a woman claimed that a scholar had betrothed her via sex,8 R’ Meir wrote her a bill of divorce (גט כריתות).

All present scholars then followed suit.9

ורבי חייא מהיכא גמיר לה?

מרבי מאיר,

דתניא:

מעשה באשה אחת

שבאתה לבית מדרשו של רבי מאיר.

אמרה לו:

רבי!

אחד מכם קדשני בביאה.

עמד רבי מאיר

וכתב לה גט כריתות

ונתן לה.

עמדו כתבו כולם, ונתנו לה.

And from where did R' Ḥiyya learn that characteristic of being willing to implicate himself in order to save someone else from being embarrassed?

He learned it from R' Meir,

as it is taught in a baraita:

There was an incident involving a certain woman

who came to the study hall of R' Meir.

She said to him:

My teacher!

one of you, i.e., one of the men studying in this study hall, betrothed me through intercourse. The woman came to R' Meir to appeal for help in identifying the man, so that he would either marry her or grant her a divorce.

As he himself was also among those who studied in the study hall, R' Meir arose

and wrote her a bill of divorce,

and he gave it to her.

Following his example, all those in the study hall arose and wrote bills of divorce and gave them to her.

In this manner, the right man also gave her a divorce, freeing her to marry someone else.

Continuing to Trace the Origin of the Practice of Emotional Self-Sacrifice to Protect Others From Embarrassment: The Case of Shecaniah ben Jehiel (Ezra 10:2, 18-44)

The Talmud states that R' Meir (in the incident described in the previous incident) learned this characteristic from Shmuel the Small (as also described in a previous section).

Shmuel the Small, in turn, learned it from Shecaniah ben Jehiel:10

Shecaniah publicly confessed that "we have broken faith (מעלנו)... and married foreign (נכריות) women".11

ורבי מאיר מהיכא גמיר לה?

משמואל הקטן.

ושמואל הקטן מהיכא גמיר לה?

משכניה בן יחיאל,

דכתיב:

״ויען שכניה בן יחיאל מבני עילם

ויאמר לעזרא:

אנחנו מעלנו באלהינו

ונשב נשים נכריות מעמי הארץ

ועתה יש מקוה לישראל על זאת״.

And from where did R' Meir learn that characteristic?

From Shmuel HaKatan, in the incident outlined above.

And from where did Shmuel HaKatan learn it?

From Shecaniah ben Jehiel,

as it is written:

“And Shecaniah, the son of Jehiel, one of the sons of Elam,

answered and said to Ezra:

We have broken faith with our God,

and have married foreign women of the peoples of the land;

yet now there is hope for Israel concerning this” (Ezra 10:2).

And although he confessed, Shecaniah is not listed among those who took foreign wives (Ezra 10:18–44). Evidently, he confessed only to spare the others from public embarrassment.

God's Refusal to Directly Expose Sinners (Joshua 7:10-11; Exodus 16:28)

The Talmud recounts stories regarding the biblical Joshua and Moses that illustrate a divine pattern: avoiding direct disclosure of individual sins, preserving communal dignity while still prompting correction:

In the aftermath of Israel’s defeat at Ai, Joshua begs God to reveal the sinner. God responds sharply—“Why are you on your face? Israel has sinned!”—but refuses to identify the culprit. Instead, He tells Joshua to cast lots,12 refusing to act as an "informer".13

Alternatively, Shecaniah may have drawn from the episode where Moses is blamed for the people’s violation of Shabbat by gathering manna.14

ושכניה בן יחיאל מהיכא גמר לה?

מיהושע,

דכתיב:

״ויאמר ה׳ אל יהושע:

קם לך!

למה זה אתה נפל על פניך?!

חטא ישראל״

אמר לפניו:

רבונו של עולם!

מי חטא?

אמר לו:

וכי דילטור אני?!

לך הטל גורלות.

ואיבעית אימא:

ממשה,

דכתיב: ״עד אנה מאנתם״.

The Gemara continues: And from where did Shecaniah ben Jehiel learn it?

From an incident involving Joshua,

as it is written:

“And YHWH said to Joshua:

Get yourself up!

why do you fall upon your face?!

Israel has sinned” (Joshua 7:10–11).

Joshua said before Him:

Master of the Universe!

who sinned?

God said to him: And am I your informer?!

Rather, cast lots to determine who is guilty. In this way, God did not directly disclose the identity of the sinner to Joshua.

And if you wish, say instead that

Shecaniah ben Jehiel learned this from an incident involving Moses,

as it is written: “And the Lord said to Moses: How long do you refuse to keep My mitzvot and My laws?” (Exodus 16:28). Although only a small number of people attempted to collect the manna on Shabbat, God spoke as though the entire nation were guilty, so as not to directly expose the guilty.

Prophetic Warnings and National Ruin: Shmuel the Small, Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel, R’ Yishmael the High Priest, and the Unmourned Death of Yehuda ben Bava

Shmuel the Small, Hillel, and the Echoes of Prophecy

After the deaths of Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi, prophecy ceased, but the phenomenon of bat kol (heavenly voice) persisted.

In one case, sages reclining (מסובין) in “Gurya’s loft”15 in Jericho heard a bat kol proclaim that Hillel the Elder was worthy of “the Shekhina resting on him”16 as it rested upon Moses, but his generation was unworthy.

The baraita adds that when Hillel died, he was eulogized as follows: Alas (הי), the pious man,17 alas, the humble man,18 a disciple of Ezra.

תנו רבנן:

משמתו נביאים האחרונים -- חגי, זכריה, ומלאכי,

נסתלקה רוח הקודש מישראל.

ואף על פי כן, היו משתמשין בבת קול.

פעם אחת

היו מסובין בעליית בית גוריה ביריחו,

ונתנה עליהם בת קול מן השמים:

יש כאן אחד שראוי שתשרה עליו שכינה כמשה רבינו,

אלא שאין דורו זכאי לכך.

נתנו חכמים את עיניהם בהלל הזקן.

וכשמת, אמרו עליו:

הי חסיד!

הי עניו!

תלמידו של עזרא!

Since Shmuel HaKatan and his great piety were mentioned, the Gemara now relates several incidents that shed additional light on his personality. The Sages taught:

After the last of the prophets, Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi, died,

the Divine Spirit of prophetic revelation departed from the Jewish people.

But nevertheless, they were still utilizing a Divine Voice, which they heard as a kind of echo of prophecy.

One time,

a group of Sages were reclining in the loft of the house of Gurya in Jericho,

and a Divine Voice was bestowed upon them from Heaven, saying:

There is one here who is fit for the Divine Presence to rest upon him as it rested upon Moses our teacher,

but his generation is not deserving of this distinction.

The Sages set their eyes upon Hillel the Elder, trusting that he was the one indicated by the Divine Voice.

And when he died,

the Sages said about him:

Alas, the pious man!

alas, the humble man!

a disciple of Ezra!

The Case of Shmuel the Small: Prophetic Potential Denied by an Unworthy Generation

A similar story is recounted about Shmuel the Small :

The sages were reclining in a loft in Yavne, when a bat kol declared Shmuel the Small worthy of “the Shekhina resting on him”.

Upon his death, he too, was eulogized as pious and humble (the same way that Hillel had been eulogized, in the previous section), and a disciple of Hillel.

שוב פעם אחת

היו מסובין בעליה ביבנה,

ונתנה עליהם בת קול מן השמים:

יש כאן אחד שראוי שתשרה עליו שכינה,

אלא שאין דורו זכאי לכך.

נתנו חכמים את עיניהם בשמואל הקטן.

וכשמת, אמרו עליו:

הי חסיד!

הי עניו!

תלמידו של הלל!

The baraita continues: Another time,

a group of Sages were reclining in the loft in Yavne,

and a Divine Voice was bestowed upon them from Heaven,

saying: There is one here who is fit for the Divine Presence to rest upon him in prophecy,

but his generation is not deserving of this distinction.

The Sages set their eyes upon Shmuel HaKatan.

And when he died, the Sages said about him:

Alas, the pious man!

alas, the humble man!

a disciple of Hillel!

Shmuel the Small’s Deathbed Prophecy of National Tragedy: Execution of Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel, R' Yishmael the High Priest, and Other Rabbis, Plunder of the People, and Looming Global Calamity

Before dying, Shmuel the Small prophesied (in literary Aramaic) the future Roman persecutions in Eretz Yisrael (in the period between c. 70 CE and 135 CE):

“Shimon (=Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel, the Nasi) and Yishmael (=R' Yishmael the High Priest), will die by the sword (חרבא; i.e. be executed),

and their colleagues will be killed (קטלא; i.e be killed in war)

and the rest of the nation will be looted (ביזא),

and great troubles (עקן) will ultimately come upon the world.”

אף הוא אמר בשעת מיתתו:

שמעון וישמעאל — לחרבא,

וחברוהי — לקטלא,

ושאר עמא — לביזא,

ועקן סגיאן עתידן למיתי על עלמא.

Additionally, he said at the time of his death, under the influence of the Divine Spirit:

Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel, the Nasi of the Great Sanhedrin, and R' Yishmael, the High Priest — will die by the sword,

and their friends — will die by other executions,

and the rest of the nation — will be despoiled,

and great troubles will ultimately come upon the world.

Yehuda ben Bava’s Missed Eulogy due to his execution by the Romans

It was wished to eulogize Yehuda ben Bava similarly, but they didn’t since “one does not eulogize those executed by the [Roman] government “.19

ועל יהודה בן בבא בקשו לומר כן,

אלא שנטרפה שעה,

שאין מספידין על הרוגי מלכות.

And they also wished to say thus: Alas, the pious man, alas, the humble man, about Yehuda ben Bava, in their eulogy for him,

but the hour was torn, i.e., the opportunity was lost,

as one does not eulogize those executed by the government.

As will be explained (14a), Yehuda ben Bava was executed by the government.

Appendix 1 - Overview Table of Main Stages in the Sugya

Appendix 2 - List of People in the ‘Return to Zion’ Period Who Had Taken Foreign Wives (Ezra 10:18-44)

A list of individuals from the 'Return to Zion' period who had married non-Israelite wives (Ezra 10:18-44). This list is understood to be implicitly referenced in the sugya discussed in the main text.20

Members of the priestly clans of Immer, Harim, and Pashhur

Among the priests found to have taken foreign wives were Jeshua son of Jozadak and his brothers, along with members of the priestly families of Immer, Harim, and Pashhur.

They pledged to send away their wives and offered a ram as atonement.

Priests

וימצא מבני הכהנים אשר השיבו נשים נכריות:

מבני

ישוע בן־יוצדק

ואחיו מעשיה

ואליעזר

ויריב

וגדליה

ויתנו ידם להוציא נשיהם

ואשמים איל־צאן על־אשמתם

Among the priestly families who were found to have brought foreign women were:

Jeshua son of Jozadak

and his brothers Maaseiah,

Eliezer,

Jarib,

and Gedaliah.

They gave their word to expel their wives

and, acknowledging their guilt, offered a ram from the flock to expiate it.

Immer

ומבני אמר:

חנני

וזבדיה

Of the sons of Immer:

Hanani

and Zebadiah;

Harim

ומבני חרם:

מעשיה

ואליה

ושמעיה

ויחיאל

ועזיה

of the sons of Harim:

Maaseiah,

Elijah,

Shemaiah,

Jehiel,

and Uzziah;

Pashhur

ומבני פשחור:

אליועיני

מעשיה

ישמעאל

נתנאל

יוזבד

ואלעשה

of the sons of Pashhur:

Elioenai,

Maaseiah,

Ishmael,

Nethanel,

Jozabad,

and Elasah

Members of the Levite clans (Jozabad, Shimei, and Eliezer), Singers (Eliashib), and Gatekeepers (Shallum, Telem, and Uri)

Several Levites, including Jozabad, Shimei, and Eliezer, were also among those who had married foreign women.

Additionally, a Temple singer (משררים) named Eliashib and several Temple gatekeepers (שערים)—Shallum, Telem, and Uri—were listed.

Levites

ומן־הלוים:

יוזבד

ושמעי

וקליה הוא קליטא

פתחיה

יהודה

ואליעזר

of the Levites:

Jozabad,

Shimei,

Kelaiah who is Kelita,

Pethahiah,

Judah,

and Eliezer.

Singers

ומן־המשררים:

אלישיב

Of the singers:

Eliashib.

Gatekeepers

ומן־השערים:

שלם

וטלם

ואורי

Of the gatekeepers:

Shallum,

Telem,

and Uri.

Members of the Israelite clans: Parosh, Elam, Zattu, Bebai, Bani, Pahath-moab, Harim, Benjamin, Hashum, and Nebo

Numerous Israelite men from various clans, including Parosh, Elam, Zattu, Bebai, Bani, Pahath-moab, Harim, Benjamin, Hashum, and Nebo, were also found to have taken foreign wives.

ומישראל:

Of the Israelites:

Parosh

מבני פרעש:

רמיה

ויזיה

ומלכיה

ומימן

ואלעזר

ומלכיה

ובניה

of the sons of Parosh:

Ramiah,

Izziah,

Malchijah,

Mijamin,

Eleazar,

Malchijah,

and Benaiah;

Elam

(Likely a toponymic clan name, meaning: from Elam.)

ומבני עילם:

מתניה

זכריה

ויחיאל

ועבדי

וירמות

ואליה

of the sons of Elam:

Mattaniah,

Zechariah,

Jehiel,

Abdi,

Jeremoth,

and Elijah;

Zattu

ומבני זתוא:

אליועני

אלישיב

מתניה

וירמות

וזבד

ועזיזא

of the sons of Zattu:

Elioenai,

Eliashib,

Mattaniah,

Jeremoth,

Zabad,

and Aziza;

Bebai

ומבני בבי:

יהוחנן

חנניה

זבי

עתלי

of the sons of Bebai:

Jehohanan,

Hananiah,

Zabbai,

and Athlai;

Bani

ומבני בני:

משלם

מלוך

ועדיה

ישוב

ושאל

(ירמות) [ורמות]

of the sons of Bani:

Meshullam,

Malluch,

Adaiah,

Jashub,

Sheal,

and Ramoth;

Pahath-moab

(This clan name means “sons of the Pasha of Moab”)

ומבני פחת מואב:

עדנא

וכלל

בניה

מעשיה

מתניה

בצלאל

ובנוי

ומנשה

of the sons of Pahath-moab:

Adna,

Chelal,

Benaiah,

Maaseiah,

Mattaniah,

Bezalel,

Binnui,

and Manasseh;

Harim

ובני חרם:

אליעזר

ישיה

מלכיה

שמעיה

שמעון

בנימן

מלוך

שמריה

of the sons of Harim:

Eliezer,

Isshijah,

Malchijah,

Shemaiah,

Shimeon

Benjamin,

Malluch,

and Shemariah;

Hashum

מבני חשם:

מתני

מתתה

זבד

אליפלט

ירמי

מנשה

שמעי

of the sons of Hashum:

Mattenai,

Mattattah,

Zabad,

Eliphelet,

Jeremai,

Manasseh,

and Shimei;

Bani (2)

מבני בני:

מעדי

עמרם

ואואל

בניה

בדיה

(כלוהי) [כלוהו]

וניה

מרמות

אלישיב

מתניה

מתני

(ויעשו) [ויעשי]

ובני

ובנוי

שמעי

ושלמיה

ונתן

ועדיה

מכנדבי

ששי

שרי

עזראל

ושלמיהו

שמריה

שלום

אמריה

יוסף

of the sons of Bani:

Maadai,

Amram,

and Uel,

Benaiah,

Bedeiah,

Cheluhu,

Vaniah,

Meremoth,

Eliashib,

Mattaniah,

Mattenai,

Jaasai,

Bani,

Binnui,

Shimei,

Shelemiah,

Nathan,

Adaiah,

Machnadebai,

Shashai,

Sharai,

Azarel,

Shelemiah,

Shemariah,

Shallum,

Amariah,

[and] Joseph;

Nebo

מבני נבו:

יעיאל

מתתיה

זבד

זבינא

(ידו) [ידי]

ויואל

בניה

of the sons of Nebo:

Jeiel,

Mattithiah,

Zabad,

Zebina,

Jaddai,

Joel,

[and] Benaiah.

Children from These Marriages

Many of these marriages had produced children.21

כל־אלה (נשאי) [נשאו] נשים נכריות

ויש מהם נשים וישימו בנים

All these had married foreign women,

among whom were some women who had borne children.

Appendix 3 - Making Talmudic Aggadah More Accessible with AI: A Case Study

Talmudic aggadah—its stories, ethics, and philosophical reflections—often feels tangled in a web of allusions, intertextuality, and cryptic dialogue. The passage we examined, drawn from a sugya on intercalating the year, demonstrates the challenges of unpacking an aggadic section.

It weaves legal discussion, ethical dilemmas, biblical exegesis, and divine intervention into a seamless whole. Yet, for those encountering it for the first time (or even for seasoned scholars), making sense of its structure and logic takes work.

This post explores how AI, particularly large language models (LLMs), can assist in clarifying such texts. Using the current piece as a case study, I'll show how breaking down a sugya into structured components—summary, visualization, and context—can enhance accessibility and understanding.

Breaking Down a Talmudic Sugya: The Need for Structure

I started with a relatively dense passage that opens with a halakhic discussion: Why do the numbers three, five, and seven appear in the process of intercalating the year? The Talmud presents a disagreement, linking the numbers to either the Priestly Benediction or the ranks of royal officials in the biblical monarchy.

From there, the sugya shifts into a narrative about Rabban Gamliel enforcing procedural rigor in intercalation. Shmuel the Small steps in to protect an anonymous attendee from embarrassment, a motif that then unravels into a chain of similar incidents—R' Ḥiyya leaving a lecture over an offensive powerful garlic smell, R' Meir issuing a divorce to protect an anonymous offender, and earlier precedents from biblical figures like Joshua and Moses.

The passage culminates with a number of “bat kol”s (heavenly voices) affirming the piety of Hillel and Shmuel the Small, linking personal virtue to divine recognition.

This movement—legal discussion → ethical stories → divine affirmation—mirrors a common flow of sugyot, where practical law gives way to the aggadic: philosophical, narrative, and moral exploration. However, the transitions are often implicit, leaving the reader to make sense of them.

Summarization: Making Implicit Structure Explicit

One of the simplest yet most effective ways to clarify a Talmudic passage is structured summarization. I distilled the sugya into titled sections, making the conceptual flow clear:

Dispute Over the Numbers – A debate over whether 3, 5, and 7 correspond to priestly blessings or royal officials.

Rav Yosef’s Baraita – A supporting tradition reinforcing the royal official explanation.

Rabban Gamliel’s Incident – A story about maintaining strict intercalation rules.

Shmuel HaKatan’s Self-Sacrifice – Protecting an unknown sage from embarrassment.

Acts of Self-Sacrifice to Protect Others – A chain of rabbinic and biblical precedents.

The Role of the Divine Voice (Bat Kol) – The link between human virtue and divine affirmation.

This type of summary transforms a sugya from an opaque mass of dialogue into a structured progression of ideas. An LLM can generate such summaries with prompts that guide it to recognize transitions and thematic shifts.

Visualization: Seeing the Structure Clearly

Beyond summarization, tables help bring order to the Talmud’s complex intertextual arguments. With the help of AI, I created a table capturing key themes and figures, turning a long-form sugya into a digestible reference format (see the table in the previous Appendix, Appendix 1).

Tables like these clarify connections and allow for quick reference. AI tools can assist by extracting key points, organizing them into logical structures, and even suggesting connections one might overlook.

Contextualizing with an Introduction

For an educated audience unfamiliar with the sugya, a strong introduction sets expectations. My AI-generated introduction framed the passage as an interplay of law, ethics, and divine affirmation, preparing the reader for its thematic shifts.

Talmudic texts rarely announce their own structure (besides for so-called ‘simanim’ (סימנים), which our sugya happens to have; I hope to discuss these in-depth in a separate discussion). A good introduction, either written manually or AI-assisted, acts as a roadmap for readers, making the text’s implicit logic explicit.

Using AI to Make Talmud More Accessible

This process—structuring, summarizing, visualizing, and contextualizing—demonstrates the power of AI in making complex rabbinic texts more accessible. While traditional Talmud study relies on extensive commentary and discussion, AI tools can:

Detect thematic transitions in sugyot.

Summarize complex discussions into structured outlines.

Generate tables to organize names, concepts, and legal principles.

Suggest introductions that highlight key themes.

These tools don’t replace in-depth study (and always need to be carefully checked and revised for accuracy, due to the well-known issue of so-called “AI hallucinations” and lack of perfect accuracy), but they serve as a meta-madrikh (study guide), helping learners at all levels grasp the Talmud’s structure and flow.

Conclusion

The sugya we explored blends halakha, ethics, and divine recognition in a way that typifies Talmudic aggadah. But without careful unpacking, its logical and thematic structure remains obscure. AI and LLMs, as I hope I've demonstrated, offer practical ways to enhance clarity—through structured summaries, visual aids, and contextual introductions.22

As AI tools improve, their ability to assist in Talmud study will (hopefully and presumably) expand, providing deeper insights while maintaining fidelity to the text. This future of Talmud learning does not replace the traditional methods (at least in the short- to medium-term), but it offers exciting new, accessible ways to illuminate the Talmud’s intricacies.

קידוש החודש - on this institution, see my piece at my Academia page formatting Mishnah Tractate Rosh Hashana, and my intro there.

שמרי הסף - i.e. who guarded the Temple “threshold” (סף).

מצבא - “mustering”.

See my intro earlier to this section, where I quote the relevant verses in II Kings.

Since these positions signify authority, the rabbis applied the same numbers to the court structure.

This gentle rebuke is classic Talmudic banter and also reveals how learning was demand-driven—students had to show initiative.

Either Gamaliel I or his grandson Gamaliel II, the ambiguity is a common one in talmudic literature; for a discussion regarding this specific story, see the Hebrew Wikipedia entry on Shmuel the Small, which I hyperlink later.

לא תהא כזאת בישראל.

It’s understood by the Talmud that he had left only to protect the real offender.

This same idiom appears elsewhere in the Talmud, again in the context of R' Yehuda HaNasi and R' Ḥiyya, but this time said by the former instead of the latter.

See my piece “Pt2 Exploring the Greatness of R' Hiyya (Bava Metzia 85b-86a)”, section “R' Yehuda HaNasi: ‘How great are the deeds of R' Ḥiyya!’ “, where the Talmud recounts a conversation highlighting R' Ḥiyya's virtuous actions:

R' Yehuda HaNasi praised R' Ḥiyya's deeds as being exceptional.

When R' Yishmael ben Yosei asked if R' Ḥiyya's deeds surpassed those of R' Yehuda HaNasi himself, R' Yehuda affirmed they did.

However, when R' Yishmael further inquired if R' Ḥiyya's deeds were greater than those of R' Yishmael’s father, R' Yosei, R' Yehuda HaNasi strongly emphasized the inappropriateness of claiming anyone's deeds surpassed those of R' Yosei within the Jewish community, stating:

“ Heaven forbid! (חס וחלילה - should say: חס ושלום)

Such a statement shall not be heard among the Jewish people”.

קדשני בביאה.

See the first Mishnah in tractate Kiddushin (Mishnah_Kiddushin.1.1), which discusses the methods of legal acquisition and release of a wife in halacha.

The Mishnah there states that a woman is “bought” (נקנית - by the man; i.e., becomes legally betrothed to him) through 1 of 3 acts: the transfer of money, the handing over of a legal document, or via sex (with her).

A woman “acquires herself “ (i.e. is divorced from her husband, exiting the marriage), through 1 of 2 events: receiving a bill of divorce (get), or upon the death of her husband.

The full passage:

האשה

נקנית בשלש דרכים,

וקונה את עצמה בשתי דרכים.

נקנית

בכסף,

בשטר,

ובביאה

[…]

וקונה את עצמה

בגט

ובמיתת הבעל

A woman

is acquired (נקנית) by, i.e., becomes betrothed to, a man to be his wife in three ways (דרכים),

and she acquires (קונה) herself, i.e., she terminates her marriage, in two ways.

The mishna elaborates: She is acquired through

money (כסף)

through a document (שטר)

and through sexual intercourse (ביאה)

[…]

And a woman acquires herself

through a bill of divorce (גט)

or through the death of the husband (מיתת הבעל)

To ensure that the actual man who had betrothed her granted her a divorce without revealing his identity.

I cited this passage in a previous piece of mine.

שכניה בן יחיאל ; he’s #5 in the list of biblical figures in Wikipedia, “Shecaniah“.

Ezra 10:2; yet he himself is not listed among those who did so in Ezra 10:18–44; this suggests that his confession was meant to protect others from shame rather than to admit personal guilt.

See Appendix 2 for reader-friendly formatting of this list in the Book of Ezra.

גורלות - i.e. to figure out the culprit via casting of lots.

See Wikipedia, “Cleromancy“:

Cleromancy is a form of sortition (casting of lots) in which an outcome is determined by means that normally would be considered random, such as the rolling of dice (astragalomancy), but that are sometimes believed to reveal the will of a deity.

In ancient Rome fortunes were told through the casting of lots or sortes.

Casting of lots (Hebrew: גּוֹרָל, romanized: gōral, Greek: κλῆρος, romanized: klē̂ros) is mentioned 47 times in the Bible.

See Wikipedia there, which goes on to list more than ten “examples in the Hebrew Bible of the casting of lots as a means of determining God's will“.

דילטור, from Latin delator.

It should be noted that two fundamental issues arise in interpreting this Talmudic passage:

First, while God’s refusal to identify the sinner (“Am I a talebearer?!”) is treated as a principled stance, this contradicts numerous biblical precedents in which God explicitly reveals individual sinners (especially via prophets).

Second, the directive to cast lots constitutes a form of divine communication in itself, as the outcome is presumably understood as reflecting God’s communication (see previous footnote on cleromancy as revealing the will of a deity)—thus there's no real distinction between direct and indirect revelation.

One might argue that the Talmud intends to distinguish between explicit and implicit disclosure.

Alternatively, it may be that the Talmud attributes cleromancy to a metaphysical mechanism, and is not a communication from God. This would make Talmudic cleromancy analogous to divining via astrology. (Astrology is a form of divination that is understood by the Talmud in a number of places as having efficacy, akin to prophecy. As an aside, in the Talmud, astrology appears as especially practiced by “Chaldeans” and Egyptians.)

Though only a few transgressed (violating Shabbat by gathering manna), God addressed Moses as if the entire people had disobeyed, thereby avoiding public exposure of the few guilty individuals.

עליית בית גוריה - likely should say “Guryon’s loft”, a famous location in rabbinic literature, mentioned a number of times in the Talmud.

A common Talmudic idiom for prophecy.

עניו; on this famous trait of Hillel’s see my previous pieces.

הרוגי מלכות.

Likely because it was considered dangerous at the time; publicly eulogizing someone executed by the Roman authorities would have been seen unfavorably by the regime.

For more on the term "those executed by the [Roman] government" (הרוגי מלכות) and the numerous Talmudic accounts of rabbis martyred by the Romans between 70 and 135 CE, see my earlier pieces on the topic.

It's worth noting that the name lists in the later biblical books contain a significantly higher number of scribal errors and uncertainties than most other biblical texts; hence the many parentheses and brackets in the Hebrew original text.

Another note: many of these clan names are mentioned in the Mishnah, see my previous pieces on this.

Highlighting the complexity of the situation, as well as the significant social consequences and the profound importance of the decision to expel the foreign wives.

Over the past year, I’ve explored this extensively in practice through my blog—nearly all of my posts have been part of a sustained investigation into it. This, however, is my first explicit, programmatic articulation of the methodology behind it.