‘Tractate Kinyanim’: Modes of Acquiring People, Livestock, Land and More (Mishnah Kiddushin 1:1-6)

This opening chapter of Mishnah tractate Kiddushin outlines the legal mechanics by which people, property, and contracts are acquired or released in Jewish law.1

It begins with a strikingly transactional framing of marriage: a woman becomes 'acquired' by a man through one of three mechanisms—money (כסף), document (שטר), or sex.

The language is direct, technical, and legalistic (reflecting the Mishnah’s interest in formal acts of acquisition, as opposed to emotional or social dynamics). Marriage is treated as a subtype of kinyan, akin to acquiring a field or a slave.

The chapter proceeds systematically, listing the modes of acquisition and release for various categories: betrothed/married women, levirate widows (יבמה), Jewish indentured servants,2 non-Jewish slaves, livestock, land, movable goods, and even consecrated Temple property.

Each subject is governed by specific legal instruments: pulling, lifting, documents, paying, or even verbal declaration in the case of sacred items.

These mechanisms differ depending on the object’s category (movable vs. immovable), the person’s status (Jewish vs. non-Jewish, male vs. female), or the institutional party involved (Temple vs. private individual).

Underlying the discussion is an interest in categorization and precision: how much is a peruta? Who must hand over the document? What counts as possession? The overall tone is procedural, aiming to define the rules that bind transactions.

For modern readers, the juxtaposition of women, slaves, and animals under a shared legal framework can be jarring. But the Mishnah’s purpose here is not moral commentary—it is structural taxonomy. It is drawing a legal map of acquisition and agency, applying consistent categories of ownership, transfer, and emancipation across domains.

Major Modes of Acquisition (Kinyan) in Talmudic Law

See Hebrew Wikipedia, “מעשה קניין”, section “מעשי קניין השונים במשפט העברי”, my translation:

There are multiple types of acquisitions, depending on the type of property:

Acquiring a woman – through money, a document, or sex.

Acquiring land – through money, a document, or chazakah (חזקה - demonstrated possession).

Acquiring movable property – through meshikhah (משיכה - “pulling”), hagbahah (הגבהה - “lifting”), use of a courtyard (חצר), or agav (אגב - acquisition of one item via another).

Acquiring animals – like other movable property, with the addition of mesirah (מסירה - transfer by handing over reins or lead) and rekivah (רכוב - mounting/riding).

Outline

Intro: Major Modes of Acquisition (Kinyan) in Talmudic Law

‘Tractate Kinyanim’: Modes of Acquisition for People and Property (Mishnah Kiddushin 1:1-6)

Women

Levirate widows (Yevama)

Indentured Servants (Jewish)

Male indentured servant

Female indentured servant

“Pierced ear” (Nirtza) indentured servant

Slaves (Non-Jewish)

Livestock

Land and Movable Property

Barter Transactions

Temple vs. Secular Property

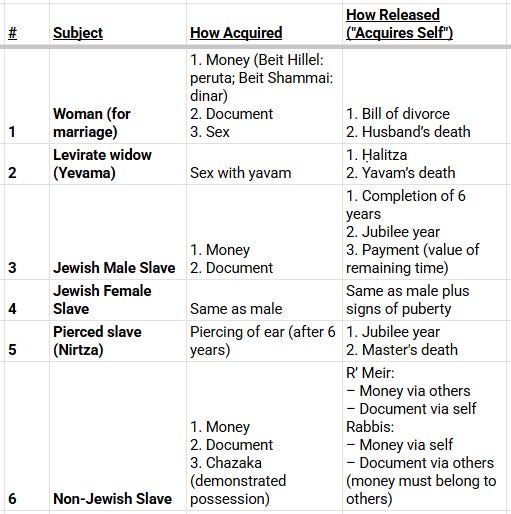

Appendix 1 - Table Summarizing the Modes of Acquisition According to Mishnah Kiddushin 1:1-6

Appendix 2 - The term ‘Chazakah’ (חזקה) in Talmudic literature

Three main definitions of Chazakah

Physical Control / Legal Possession

Legal Presumption / Status Quo

Behavioral Heuristic / Pattern of Conduct

Semantic Summary

The Passage

Women

A woman becomes betrothed (נקנית - literally: “acquired”) to a man via one of three mechanisms:

Money (כסף)

Document (שטר)

Sex (ביאה)

Beit Shammai require at least a dinarius or its value; Beit Hillel permit even a peruta (a minimal coin).

A married woman exits the marriage through one of two mechanisms:

האשה --

נקנית בשלש דרכים,

וקונה את עצמה בשתי דרכים.

נקנית

בכסף,

בשטר,

ובביאה.

בכסף,

בית שמאי אומרים:

בדינר

ובשוה דינר.

ובית הלל אומרים:

בפרוטה

ובשוה פרוטה.

וכמה היא פרוטה?

אחד משמנה באסר האיטלקי.

וקונה את עצמה

בגט

ובמיתת הבעל.

A woman is acquired by, i.e., becomes betrothed to, a man to be his wife in three ways,

and she acquires herself, i.e., she terminates her marriage, in two ways.

The mishna elaborates: She is acquired

through money,

through a document,

and through sexual intercourse.

With regard to a betrothal through money, there is a dispute between tanna’im:

Beit Shammai say that

she can be acquired with one dinar

or with anything that is worth one dinar.

And Beit Hillel say:

She can be acquired with one peruta, a small copper coin,

or with anything that is worth one peruta.

The mishna further clarifies: And how much is the value of one peruta, by the fixed value of silver?

The mishna explains that it is one-eighth of the Italian issar, which is a small silver coin.

And a woman acquires herself

through a bill of divorce

or through the death of the husband.

Levirate widows (Yevama)

A yevama (levirate widow) is acquired only through sex with her late husband's brother (yavam) and released through ḥalitza or the yavam’s death.

היבמה --

נקנית

בביאה.

וקונה את עצמה

בחליצה

ובמיתת היבם

A woman whose husband, who had a brother, died childless [yevama] —

can be acquired by the deceased husband’s brother, the yavam,

only through intercourse.

And she acquires herself, i.e., she is released from her levirate bond,

through ḥalitza

or through the death of the yavam.

Indentured Servants (Jewish)

Male indentured servant

A male Jewish indentured servant (עבד עברי) is acquired via money or document, and released either after 6 years (שנים), at the Jubilee year, or by repaying the value of the remaining term (גרעון כסף).

עבד עברי --

נקנה

בכסף

ובשטר,

וקונה את עצמו

בשנים

וביובל

ובגרעון כסף.

A Hebrew slave --

can be acquired by his master

through money

or through a document,

and he can acquire himself, i.e., he is emancipated,

through years, i.e., when he completes his six years of labor,

or through the advent of the Jubilee Year,

or through the deduction of money. The slave can redeem himself during the six years by paying for his remaining years of slavery.

Female indentured servant

A female Jewish indentured servant (אמה העבריה) has an additional route: signs (סימנין) of puberty.4

יתרה עליו אמה העבריה --

שקונה את עצמה

בסימנין

A Hebrew maidservant has one mode of emancipation more than him --

as she acquires herself

through signs indicating puberty.

“Pierced ear” (Nirtza) indentured servant

A “pierced ear” Jewish indentured servant (נרצע - nirtza) is acquired by ear-piercing and released through the Jubilee or the master’s death.

הנרצע --

נקנה

ברציעה,

וקונה את עצמו

ביובל

ובמיתת האדון

A slave who is pierced after serving six years is acquired as a slave for a longer period

through piercing his ear with an awl,

and he acquires himself

through the advent of the Jubilee Year

or through the death of the master.

Slaves (Non-Jewish)

According to R' Meir, a non-Jewish slave is acquired by money, document, or chazaka,5 and can free himself via money from others or a document (שטר) accepted himself.

The Sages reverse the roles: the slave may use his own money (if owned by others) or have a document accepted by others.

עבד כנעני --

נקנה

בכסף

ובשטר

ובחזקה,

וקונה את עצמו

בכסף —

על ידי אחרים,

ובשטר —

על ידי עצמו,

דברי רבי מאיר.

וחכמים אומרים:

בכסף —

על ידי עצמו

ובשטר —

על ידי אחרים,

ובלבד שיהא הכסף משל אחרים

A Canaanite slave --

is acquired

by means of money,

by means of a document,

or by means of the master taking possession of him.

And he can acquire himself, i.e., his freedom,

by means of money —

given by others, i.e., other people can give money to his master,

and by means of a bill of manumission —

if he accepts it by himself.

This is the statement of R' Meir.

And the Rabbis say:

The slave can be freed

by means of money —

given by himself,

and by means of a bill of manumission —

if it is accepted by others,

provided that the money he gives belongs to others, not to him. This is because the slave cannot possess property, as anything owned by a slave is considered his master’s.

Livestock

Cattle6 are acquired by handing over (מסירה - ‘mesira’), sheep and goats (בהמה דקה - “small animals”) by lifting (הגבהה - ‘hagbaha’) per R' Meir and R' Eliezer; the Sages state that sheep and goats are acquired via pulling (משיכה - ‘meshikha’).

בהמה גסה --

נקנית

במסירה,

והדקה --

בהגבהה,

דברי רבי מאיר ורבי אליעזר.

וחכמים אומרים:

בהמה דקה --

נקנית

במשיכה

A large domesticated animal --

is acquired

by passing, when its current owner transfers it to a buyer by giving him the reins or the bit.

And a small domesticated animal --

is acquired

by lifting.

This is the statement of R' Meir and R' Eliezer.

And the Rabbis say:

A small domesticated animal --

can be acquired

by pulling also, and there is no need to lift it.

Land and Movable Property

Land7 can be acquired by money, document, or chazaka (חזקה).

Movables8 require pulling (משיכה) unless acquired alongside land through a unified transaction.

נכסים שיש להם אחריות --

נקנין

בכסף

ובשטר

ובחזקה.

ושאין להם אחריות --

אין נקנין אלא

במשיכה.

נכסים שאין להם אחריות --

נקנין עם נכסים שיש להם אחריות,

בכסף

ובשטר

ובחזקה.

[...]

Property that serves as a guarantee, i.e., land or other items that are fixed in the earth --

can be acquired

by means of giving money,

by means of giving a document,

or by means of taking possession of it.

Property that does not serve as a guarantee, i.e., movable property,

can be acquired only by

pulling.

Property that does not serve as a guarantee --

can be acquired along with property that serves as a guarantee

by means of giving money,

by means of giving a document,

or by means of taking possession of them.

The movable property is transferred to the buyer’s possession when it is purchased together with the land, by means of an act of acquisition performed on the land.

Generally, one is not obligated to take an oath concerning the denial of a claim with regard to land.

[...]

Barter Transactions

The Mishna posits that in barter transactions—where one item is exchanged for another, rather than money for goods—ownership is transferred upon acquisition by one party.

Once one side "acquires" the object being offered, the other party becomes legally obligated for the object they receive, even if no physical transfer has yet occurred.

For example, if one person exchanges (החליף) an ox for a cow or a donkey for an ox, once one party has acquired their item, the deal is binding, and the other party bears responsibility (נתחיב) for the exchanged item.

כל הנעשה דמים באחר --

כיון שזכה זה,

נתחיב זה בחליפיו.

כיצד?

החליף

שור בפרה

או חמור בשור,

כיון שזכה זה,

נתחיב זה בחליפיו.

The mishna discusses a transaction involving the barter of two items.

With regard to all items used as monetary value for another item, i.e., instead of a buyer paying money to the seller, they exchange items of value with each other,

once one party in the transaction acquires the item he is receiving,

this party is obligated with regard to the item being exchanged for it. Therefore, if it is destroyed or lost, he incurs the loss.

How so?

If one exchanges

an ox for a cow,

or a donkey for an ox,

once this party acquires the animal that he is receiving,

this party is obligated with regard to the item being exchanged for it.

Temple vs. Secular Property

The Mishna contrasts acquisition modes for sacred (Temple) property versus secular (private) property.

The Temple treasury (רשות הגבוה) acquires ownership through monetary payment alone (כסף - i.e. no physical transfer is required).

In contrast, a regular individual9 must effect acquisition through chazaka.

Additionally, the Mishna asserts that verbal consecration (אמירתו) of an item to the Temple10 is treated as legally binding, equivalent to a formal transfer (מסירתו) to a private party.

רשות הגבוה --

בכסף,

ורשות ההדיוט --

בחזקה.

אמירתו לגבוה,

כמסירתו להדיוט

The authority of the Temple treasury effects acquisition

by means of money to the seller.

And the authority, i.e., the mode of acquisition, of a commoner [hedyot]

is by possession.

Furthermore, one’s declaration to the Most High, i.e., when one consecrates an item through speech,

is equivalent to transferring an item to a common person, and the item is acquired by the Temple treasury through his mere speech.

Appendix 1 - Table Summarizing the Modes of Acquisition According to Mishnah Kiddushin 1:1-6

Appendix 2 - The term ‘Chazakah’ (חזקה) in Talmudic literature

The term chazakah (חזקה) in Talmudic literature carries a semantic range that spans legal, evidentiary, and even cognitive or heuristic domains.

It is derived from the verb ḥ-z-k (ח-ז-ק), which in its core sense means ‘strength’, but in legal and Talmudic usage develops into several technical meanings.

These can be grouped broadly into three main domains:

Three main definitions of Chazakah

1. Physical Control / Legal Possession

This is the most tangible and practical sense.

In real estate and property law, chazakah refers to an act that signifies effective control or usage of land—such as fencing, sowing, or locking—which under certain conditions can transfer ownership.

This usage appears prominently in Bava Batra ch. 3 and is codified in the Mishnah and Talmud as a mode of kinyan (acquisition).

It is similar to the Roman law concept of usucapio (acquisition by long-term possession).

Key feature: it functions not only as evidence of ownership but as a means of acquisition (a ma’aseh kinyan).

2. Legal Presumption / Status Quo

In a more abstract sense, chazakah came to mean (in the Talmud Bavli, post-Mishnah) a legal presumption or status quo assumption.

Examples include:

Chazakah demei’ikara (חזקה דמעיקרא) — assuming prior status continues unless proven otherwise.

Chezkat ha-guf (חזקת הגוף) — assuming bodily status persists (e.g., a woman’s prior non-menstruating status).

Chezkat mamon (חזקת ממון) — the presumption that current possession indicates ownership.

In these cases, chazakah sets the burden of proof: it defaults in favor of continuity or possession.

3. Behavioral Heuristic / Pattern of Conduct

Some usages of chazakah function even more broadly, as psychological or behavioral heuristics.

For instance:

Ein adam me’iz panav bifnei ba’al ḥovo (חזקה אין אדם מעיז פניו בפני בעל חובו) — a person won’t brazenly deny debt face-to-face; a behavioral presumption treated as a legal axiom.

Two or three consistent events establish a pattern. This is used to infer likely continuation of behavior or outcome.11

These are not axiomatic legal rules but inferential tools based on empirical expectations.12

Semantic Summary

The underlying thread among these meanings is the notion of strength or stability—whether in physical control, legal standing, or behavioral expectation.

The term oscillates between evidence of a state, presumption in favor of continuity, and instrument of change (in property law).

The ambiguity often arises because chazakah may serve both as a legal effect and as an evidentiary mechanism, blurring the line between proof and substance. There’s often ambiguity as to when chazakah is merely epistemic and when it is constitutive.

Bottom line: chazakah is best understood not as a single concept, but as a spectrum of overlapping uses rooted in the idea of 'established strength'—whether of fact, right, or expectation.

The term ‘Tractate Kinyanim’ comes from Menachem Katz, who identifies this extended Mishnaic passage as a complete unit, focused on Modes of Acquisition for People and Property.

(מנחם כ״ץ, כיצד נקנית הארץ? העושה מצוה: ניתוח ספרותי של סיום "מסכת הקניינים" במשנה)

Thanks to Prof. Katz for providing me with his article.

See also Avraham Walfish, חקר עריכתו של פרק א במשנה קידושין (also here: אברהם וולפיש, חקר עריכתו של פרק א במשנת קידושין - מאין ולאן?, נטועים טו (תשס"ח), עמ' 43-77), and Noam Zohar, Secrets of the Rabbinic Workshop: Redaction as a Key to Meaning (2007, Hebrew), p. 11 and on.

This piece is a continuation of my research on literary structure in the Mishnah, see my recent 3-part series on this topic, “Revealing the Order: Literary Structure and Rhetoric in the Mishnah”, final part here.

It’s worth noting that the Talmud Bavli’s commentary on this chapter is the longest chapter in that work, both in terms of word count, and in terms of the traditional print pagination (originating in the 16th ed. Venice-Bomberg).

See on this my piece at Academia, on word counts of all chapters of Talmud Bavli.

The second longest is Perek Chelek in Sanhedrin.

The Talmud’s commentary is unusually long here likely because the tractate covers a broad array of subjects, providing a pretext to explore many of them in depth. For instance, this chapter contains the Talmud’s primary discussion of the halakhic laws of slavery.

עבד עברי - ed. Steinsaltz translates this term as ‘Hebrew slave’, which--while common--I believe is less accurate and misleading.

See discussion at Wikipedia, “Jewish views on slavery”, section “Biblical era”, especially this line:

In English translations of the Bible, the ethnic distinction is sometimes emphasized by translating the word ebed (עבד) as "slave" in the context of non-Hebrew slaves, and "servant" or "bondman" for Hebrew slaves.

Compare Katz’s formatting of this chapter, ibid., p. 144-145.

The standard ‘sign of puberty’ in Talmudic literature is two pubic hairs (שתי שערות).

See my note here: “Pt2 Fig Metaphors and Female Development: Puberty, Maturity, and Majority (Niddah 47a-b)“, where I write, inter alia:

“Two [pubic] hairs” is a common term in the Talmud.

See Hebrew Wikipedia, “שתי שערות“, my translation:

“The term "two hairs" is a concept in halacha. The appearance of two pubic hairs marks the attainment of physical maturity (בגרות) and thereby entrance into the realm of halakhic obligation.”

חזקה - i.e. demonstrated control.

It’s worth noting that the technical Hebrew term chazaka has range of loosely related technical meanings in Talmudic literature.

See a relatively extensive elaboration the Mishnah_Bava_Batra Chapter 3.

And see Hebrew Wikipedia, “קניין חזקה“.

On one (possibly different) major sense, see Wikipedia, Chazakah, with adjustments:

A chazakah (Hebrew: חֲזָקָה, romanized: ḥəzāqā, lit. [‘strength’]) is a legal presumption in halakha (Jewish law); it establishes burden of proof.

There exist many such presumptions, for example, regarding the ownership of property, a person's status (e.g. whether they are a kohen or Levite), and presumptions about human behavior.

The Hebrew word חזקה is a noun form of the verb חזק […]

The conceptional terminology is "default status," "agreed properties," or status quo of an object, land or person − usually when [stronger] proof is missing or unavailable.

The concept is relevant to many aspects of Talmudic law and halakha.

There are various ways how something can obtain the state of chazakah […]

Another major sense of the terms is roughly “heuristic”.

Its meaning in many cases is somewhat ambiguous, and has extensive discussion in the Talmud and later interpreters; see at length in Hebrew Wikipedia, חזקה (הלכה).

And see my appendix on this at the end of this piece: “Appendix 2 - The term ‘Chazakah’ (חזקה) in Talmudic literature”.

בהמה גסה - “large animals”.

On the standard Mishnaic/Talmudic categorization of livestock into the categories “large” and “small”, see my note in “Labor, Lamps, and Livestock: Local Norms, Pluralism, and Halachic Variance by Time and Place (Mishnah Pesachim 4:1-5)”, where I write:

בהמה דקה - “small livestock“.

This is the standard term used in the Talmud to refer to sheep and goats, as a class, as opposed בהמה גסה ("large livestock"), which refers especially to cattle, but also to other large domesticated working animals such as donkeys, camels, and horses (essentially, pack animals and large draft animals).

These are important categories that are used in the context of multiple domains of halacha.

נכסים שיש להם אחריות - “property with a guarantee”.

שאין להם אחריות - “[property] without a guarantee”.

הדיוט - from Greek idiotes.

גבוה - “High”.

On this, see for example my “Stories of Marriage, Mortality, and Mishaps: The Talmud’s Views on Consecutive Calamities (Yevamot 64b)“.

For an extensive list of such presumptions—many of them explicitly referred to by the Talmud as a chazakah—see this Hebrew Wikipedia category: