A Computational Approach to Identifying and Mapping Aggadic Content in the Talmud: Word Count as a Robust Proxy Indicator

A continuation of the discussion in yesterday’s piece :”The Densest Daf - Which Page of the Talmud Contains the Most Text? A Word Count Analysis That Definitively Identifies the Talmud’s Wordiest Pages”.

My analysis of the Talmud's word density patterns shows very interesting clusters of aggadic material throughout the length of the Talmud. By identifying sequences of pages with high word counts (≥450 words per page), clear patterns of extended aggadic sugyot emerge.1

The following sections highlight the most significant patterns discovered through this digital humanities approach.

Outline

Major Aggadic Sequences

Tractates with Highest Concentration of Aggadic Content

The Densest Aggadic Sections

Important 3-Page Aggadic Windows

Tractate-Specific Noteworthy Aggadic Sections

Patterns and Observations

Distribution Patterns Within Tractates

Practical Implications

Case Study: Visualizing Aggadic Density in Tractates Berakhot and Shabbat — Bar Charts of High-Word-Count “Aggadic Islands” with Annotations Based on Previous Work

Screenshots / Figures

Figure 1 - Berakhot - bar chart - Entire Tractate

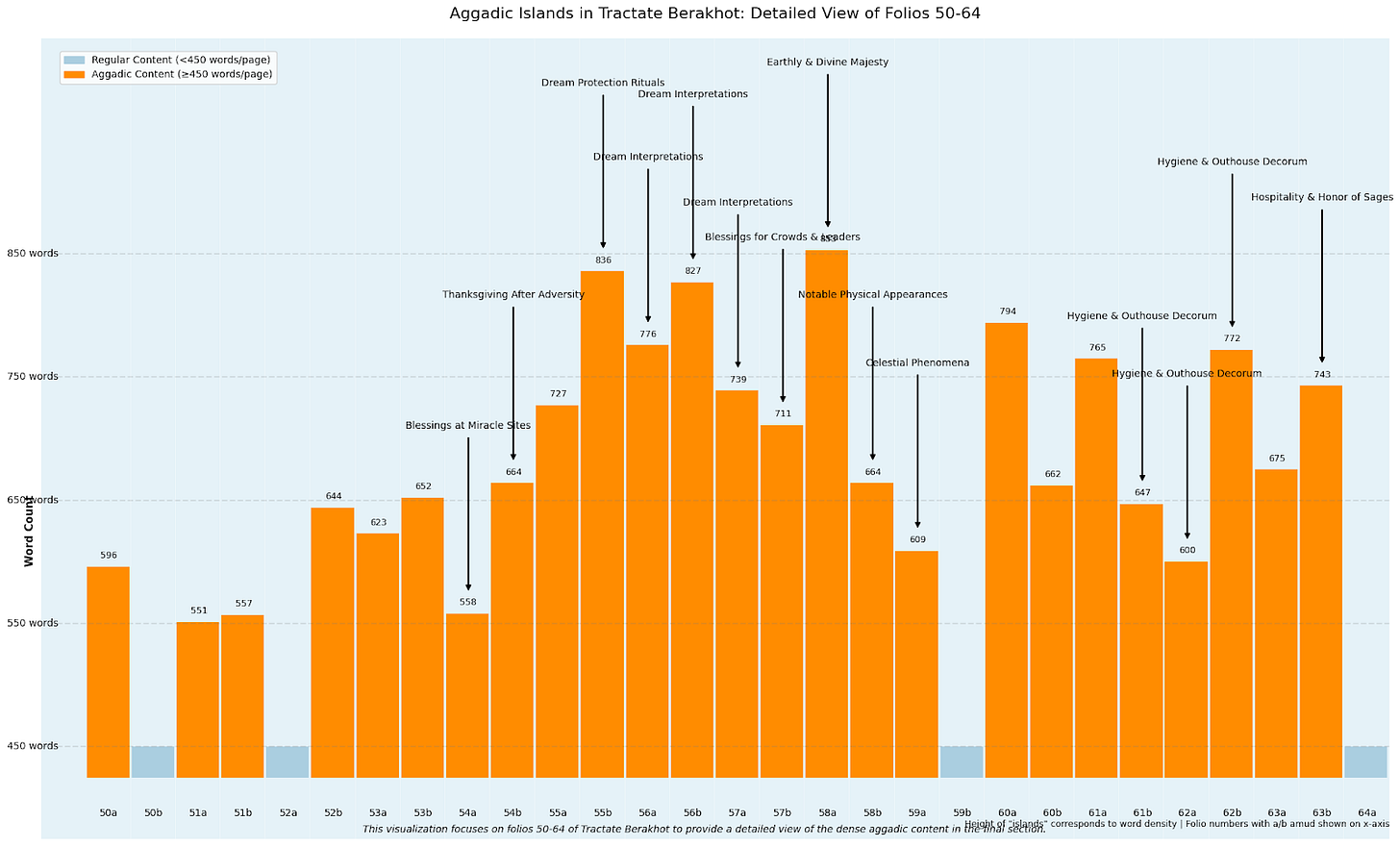

Figure 2 - Tractate Berakhot - bar chart - “Zoomed-in” to folios 50-64

Figure 3 - Tractate Shabbat - bar chart - Entire Tractate

Figure 4 - Tractate Shabbat- bar chart - “Zoomed-in” to folios 100-157

Figure 5 - Tractate Shabbat- bar chart - “Zoomed-in” to folios 25-35

Figure 6 - Tractate Berakhot - ‘Heat Map’ visualization - Entire Tractate

Figure 7 - Tractate Shabbat - ‘Heat Map’ visualization - Entire Tractate

Figure Description: "Aggadic Islands in Tractate Berakhot"

Key to Interpretation

Notable Patterns

Methodology

Significance

Appendix - On the Definition of ‘Aggadah’

Major Aggadic Sequences

Sanhedrin 88b-112a: The longest aggadic sequence by far, spanning 48 consecutive pages with an average of 619 words per page.2 This corresponds to the famous "Perek Chelek" (Chapter 11) of Sanhedrin, with its extensive discussions of the World-to-Come, Messianic era, and other fundamental aggadic topics.

Berakhot Contains Multiple Dense Sequences:

Berakhot 4b-11a: 14 consecutive pages (avg. 661 words)

Berakhot 27a-33b: 14 consecutive pages (avg. 651 words) - includes the wordiest page, Berakhot 32a (883 words)

Berakhot 52b-59a: 14 consecutive pages (avg. 706 words)

Sotah 42a-49b: 16 consecutive pages (avg. 583 words) - This section contains the "Egla Arufa" material and discussions about the End-of-Days.

Keritot 2b-8a: 12 consecutive pages (avg. 663 words)

Tractates with Highest Concentration of Aggadic Content

When looking at the percentage of each tractate covered by high-density sequences:

Berakhot: 64.8% of its pages are part of high-density sequences

Horayot: 56.0%

Megillah: 45.9%

Keritot: 38.9%

Sanhedrin: 38.0%

The Densest Aggadic Sections

Some of the densest sequences (representing the most concentrated aggadic material) identified are:

Berakhot 55b-56b: Average 813 words per page - This section discusses dreams and their interpretations

Berakhot 31b-33a: Average 796 words per page - Contains Moses's prayer after the Golden Calf incident, and discussion on prayer methodology

Gittin 56a-58a: Average 707 words per page - The destruction of the Second Temple and the Bar-Kokhba revolt

Berakhot 10a-10b (845 words/page): Contains stories about King Hezekiah and the prophet Isaiah, and R' Yose's encounters in a ruin.

Berakhot 31b-32a (822 words/page): Moses's prayer after the Golden Calf incident.

Berakhot 55b-56a (806 words/page): Dream interpretation.

Sanhedrin 107b-108a (788 words/page): The Generation of the Flood.

Gittin 57a-57b (785 words/page): The destruction of the Temple and the city of Beitar.

Bava Batra 16a-16b (768 words/page): Job's suffering and the nature of Satan.

Keritot 5a-5b (774 words/page): The anointing oil and its significance.

Megillah 10b-11a (749 words/page): The story of Ahasuerus and historical context of the Purim story.

Important 3-Page Aggadic Windows

Bava Metzia 84b-85b (650+ words/page): The stories of R' Eleazar ben Shimon and R' Yochanan.

Eruvin 53b-54b (649 words/page): Methods of Torah study.

Yoma 86b-87a (681 words/page): Repentance and atonement.

Tractate-Specific Noteworthy Aggadic Sections

Chagigah:

Chagigah 12a-12b (666 words/page): Creation of the world.

Chagigah 13b-14a (653 words/page): Ma'aseh Merkavah (the Divine Chariot).

Moed Katan:

Moed Katan 16b-17a (717 words/page): Stories of rabbinic excommunications.

Ketubot:

Ketubot 111a-111b (742 words/page): The praises of the Land of Israel.

Sotah:

Sotah 46b-47a (733 words/page): The broken-necked heifer ritual and the signs of the Messianic age.

Taanit:

Taanit 23a-23b (664 words/page): The story of Honi the Circle-Drawer.

Patterns and Observations

Underrated Dense Sections: While Berakhot and Sanhedrin are well-known to have dense aggadic content, this analysis shows concentrated aggadic sections in tractates such as Keritot, Bava Metzia, and Eruvin.

Thematic Clusters: Many dense sections cluster around specific themes:

Destruction narratives: Gittin 56a-58a and Sanhedrin 104a-105a

Messianic expectations: Sanhedrin 98a-99b and Sotah 46b-49b

Creation and cosmology: Chagigah 12a-14b

Stories of the righteous: Taanit 23a-24b (miracle workers) and Bava Metzia 84b-85b (sages' stories)

Isolated Dense Pages: Some tractates have single pages with extremely high word counts that appear as isolated aggadic sections:

Bava Batra 16a (833 words) - Job's suffering

Chagigah 5b (778 words) - Divine justice and weeping

Shabbat 119b (777 words) - The sanctity of Shabbat

Final Pages Phenomenon: Many tractates show dense aggadic material in their final pages (e.g., Ketubot, Sotah, Gittin), suggesting a pattern of concluding tractates with aggadic material.

This mapping of 2-4 page aggadic windows thus provides an initial guide to some of the concentrated narrative and homiletical material throughout the Talmud.

Distribution Patterns Within Tractates

Many tractates show uneven distribution of aggadic material:

Sanhedrin: Heavily concentrated in its later chapters (=Perek Chelek, as mentioned)

Gittin: Aggadic material concentrated in the middle (primarily Destruction narratives)

Bava Batra: 81% of its aggadic material appears in the beginning of the tractate

Taanit: 78% of its aggadic material appears at the end

Practical Implications

Studying Aggadah: If you want to study concentrated aggadic material, focus on the sequences identified above, especially Sanhedrin 88b-112a and the multiple dense sections in Berakhot.

Berakhot's Uniqueness: The data confirms Berakhot is exceptionally rich in aggadah, with over 64% of its pages containing dense content.

Transitional Patterns: Many tractates show significant changes in word density at specific transition points, which could indicate shifts between halachic and aggadic sections.

This analysis provides empirical confirmation of many traditional observations about aggadic content in the Talmud, while showing patterns in how this material is distributed across and within tractates.

Case Study: Visualizing Aggadic Density in Tractates Berakhot and Shabbat — Bar Charts of High-Word-Count “Aggadic Islands” with Annotations Based on Previous Work

Figure Description: "Aggadic Islands in Tractate Berakhot"

This visualization acts as a case study, mapping the distribution and density of aggadic content throughout Tractate Berakhot.3

Tthe chart represents each page of Berakhot as a vertical bar, with height corresponding to number of words.4

Key to Interpretation

Orange Bars: Pages with ≥450 words, identified as aggadic content

Blue Bars: Pages with <450 words, typically representing more halachic or technical content

Height of Bars: Proportional to word count, with taller "islands" indicating denser aggadic material

X-Axis: Folio (daf) numbers. Each folio also comprises an 'a' side and 'b' side; due to space constraints in the visualization, that the actual labels a/b aren’t shown in Figure 1, they’re only shown in Figure 2.

Y-Axis: Word count scale, ranging from 450 to 850 words per page

Text Labels: Identify specific aggadic topics in each high-density section that I discussed in a previous piece or series

Figure 1 - Berakhot - whole tractate:

Figure 2 - Tractate Berakhot - “Zoomed-in” to folios 50-64:

(Focused Range: Only displays folios 50-64, allowing more space for each page. This allows for enhanced readability, better label placement, visual clarity, and enhanced annotations.)

Figure 3 - Tractate Shabbat - Entire Tractate:

Figure 4 - Tractate Shabbat- “Zoomed-in” to folios 100-157:

Figure 5 - Tractate Shabbat- “Zoomed-in” to folios 25-35:

Figure 6 - Tractate Berakhot - ‘Heat Map’ visualization - Entire Tractate

(Wikipedia, “Heat map“: A heat map (or heatmap) is a 2-dimensional data visualization technique that represents the magnitude of individual values within a dataset as a color. The variation in color may be by hue or intensity.”)

Figure 7 - Tractate Shabbat - ‘Heat Map’ visualization - Entire Tractate

Notable Patterns

The visualization reveals several significant concentrations of aggadic material in Berakhot:

Dream Interpretation Cluster (folios 55-57): The densest section, containing extensive dream interpretation material with word counts exceeding 800 words per page.

Prayer Content (folios 31-33): Contains Moses's prayer after the Golden Calf incident, reaching 883 words on folio 32a (the wordiest page in the entire Talmud).

Ethical Teachings (folios 16-17): Notable concentration of Talmudic prayers and ethical teachings.

Distributed Thematic Clusters: Other aggadic sections highlighted include discussions of extraordinary fruits and families (folio 44), blessings at miracle sites (folio 54), and discussions of hygiene and outhouse decorum (folios 61-62).

Sequential Patterns: Multiple sequences of 3+ consecutive high-density pages, suggesting extended aggadic sugyot rather than isolated aggadic comments.

Significance

The "aggadic islands" metaphor effectively illustrates how narrative and homiletical material rises from the surrounding sea of more technical discourse, creating an intuitive visual representation of the textual landscape of tractates Berakhot and Shabbat.

In addition, these charts provides empirical confirmation of traditional observations about Berakhot's high concentration of aggadic material while revealing specific patterns in how this content is distributed throughout the tractate.

Appendix - On the Definition of ‘Aggadah’

A broader point I raised in a comment on yesterday’s post: I use the term "aggadah" in a functional sense. For my purposes, it means anything in the Talmud that isn’t halakhic argument or legal reasoning.

That includes narratives (biblical or rabbinic), folklore, ethics, theology, cosmology, metaphysics, demonology, medicine, and various observations on language or nature. I’m not using "aggadah" as a fixed literary genre (like homiletics), but as a catch-all for non-legal Talmudic discourse.

This is in contrast to more restrictive definitions of "aggadah," defines it primarily as Biblical narrative and moral content. That “strict sense” excludes a lot of the non-legal material I would count.

The question of how to define "aggadah" is itself very much worth exploring. There's been serious discussion in modern scholarship, though less from a quantitative, thematic, or NLP-driven angle, which is what I’m particularly interested in.

As for the original meaning of the term, as it appears in Talmudic literature, see Hebrew Wikipedia, “אגדה (יהדות)“, section “המושג "אגדה" בלשון חז"ל“, my translation (with additional slight adjustments):

In common usage, "Midrash of the Sages" (מדרשי חז"ל) refers to all non-halakhic material in Talmudic literature: ethical teachings, philosophical and wisdom literature, stories, and parables.

However, in Talmudic Hebrew, the term "Midrash" (or "story") refers to a very specific genre: interpretation of biblical verses that does not involve practical halakha.

Examples of this in rabbinic usage include:

[T]he people of Alexandria asked R’ Yehoshua ben Ḥanania a number of questions, among them: "three matters of aggadah, and three matters of proper conduct (דרך ארץ - derekh eretz)". In the [ensuing] account of the "aggadah," the Talmud lists three questions about biblical verses, while the matters of "proper conduct" are a separate category and not considered "aggadah."

It is also said of the sermons of R’ Meir that they included: "one-third halakhot, one-third aggadot, and one-third parables (משלים - mashal)".

In the Tosefta, it is stated regarding a sermon by R’ Elazar ben Azaria: "Where was the aggadah? 'Gather the men, the women, and the children.'" The question "Where was the aggadah?" means: which verse was it based on.

The Passover Haggadah is called that because it centers on biblical verses describing the Exodus from Egypt, which it expands on and interprets.5

Accordingly, books of "aggadah" were organized according to the books of the Bible. The "Rabbis of the Aggadah" (רבנן דאגדתא) or "masters of aggadah" (בעלי הגדה) were those sages who specialized in interpreting biblical verses in depth, and anyone struggling to understand a particular verse would turn to them. The leading experts among them developed special methods for understanding Scripture.

And see “Aggadah“, section “Modern compilations“, with slight adjustments:

Ein Yaakov is a compilation of the aggadic material in the Babylonian Talmud together with commentary. It was compiled by Jacob ibn Habib and (after his death) by his son Levi ibn Habib, and was first published in Saloniki (Greece) in 1515. It was intended as a text of aggadah, that could be studied with "the same degree of seriousness as the Talmud itself".

Popularized anthologies did not appear until more recently—these often incorporate "aggadot" from outside of classical Rabbinic literature. The major works include:

Sefer Ha-Aggadah (The Book of Legends) is a classic compilation of aggadah from the Mishnah, the two Talmuds and the Midrash literature.

It was edited by Hayim Nahman Bialik and Yehoshua Hana Rawnitzki.

Bialik and Ravnitzky worked for three years to compile a comprehensive and representative overview of aggadah.

When they found the same aggadah in multiple versions, from multiple sources, they usually selected the later form, the one found in the Babylonian Talmud.

However, they also presented some aggadot sequentially, giving the early form from the Jerusalem Talmud, and later versions from the Babylonian Talmud, and from a classic midrash compilation.

In each case every aggadah is given with its original source.

In their original edition, they translated the Aramaic aggadot into modern Hebrew.

Sefer Ha-Aggadah was first published in 1908–1911 in Odessa, Russia, then reprinted numerous times in Israel […]

Legends of the Jews, by Louis Ginzberg, is an original synthesis of a vast amount of aggadah from the Mishnah, the two Talmuds and Midrash.

Ginzberg had an encyclopedic knowledge of all rabbinic literature, and his masterwork included a massive array of aggadot.

However he did not create an anthology which showed these aggadot distinctly.

Rather, he paraphrased them and rewrote them into one continuous narrative that covered five volumes, followed by two volumes of footnotes that give specific sources.

This computational analysis was executed through detailed prompting of Claude 3.7's extended thinking mode, with substantial editorial refinement of the output.

As I qualified in my note in yesterday’s piece, in “Appendix - In-depth Analysis of Talmud Word Count Distribution (by Claude AI):

Important note: This analysis was generated by Claude AI. I haven’t reviewed it closely, so each data point should be treated with caution and independently verified/confirmed.

While I haven't manually verified every analysis, spot-checking confirms the findings, and it overall aligns with established scholarly understanding of the Talmud's structure.

And Claude's well-known accuracy in factual representation gives me overall measured confidence in these results.

Relatedly, this chapter is the second-longest one in the Talmud, by word count; see my piece on this at my Academia page: “Bavli By the Numbers: Word Counts of All Chapters in Talmud Bavli“. It appears in the table there at beginning of p. 4. See my discussion there, in general. And see my comment in yesterday’s piece on some of the issues with using Wikisource as a base text for word count; I hope at some point to revisit this count and to find a better, more accurate solution using Sefaria’s base text.

The first tractate of the Babylonian Talmud, and the one with the highest density of aggadah, as is well-known, and as I’ve mentioned and demonstrated quantitatively few times in this series.

See Wikipedia, “Berakhot (tractate)“, section “Structure and content“:

The tractate [=Berakhot] consists of nine chapters and 57 paragraphs (mishnayot).

[There are] 64 double-sided pages [=folios] in the standard [19th century] Vilna-[Romm] Edition […] of the Babylonian Talmud […]

Tractate Berakhot in the Babylonian Talmud has the highest word per daf average due to its large quantity of aggadic material.

Some of these passages offer insights into the rabbis' attitudes towards prayer, often defined as a plea for divine mercy, but also cover many other themes, including biblical interpretations, biographical narratives, interpretation of dreams, and folklore.

There’s no source given for the assertion that “Tractate Berakhot in the Babylonian Talmud has the highest word per daf average due to its large quantity of aggadic material.”

On Berakhot as having the highest word per daf, see Ari Z. Zivotofsky, “The Longest Masechta is …” (March 31, 2023) at the Seforim Blog:

So why might one have been (mis)led to think that Berachot is the largest?

It is easy to understand because Berachot does indeed win the prize in one category – words/daf.

Berachot is king, with over 1115 words/daf.

And for word counts of other related works, see my “Words of Wisdom: Word Counts of Classical Jewish Works“, with further bibliography there.

See the full code in the Google Colab notebook here: Visualization of Aggadic Content in Tractate Berakhot: A bar chart showing Aggadic Islands (>450 words/page) in Tractate Berakhot, with labels highlighting my previous pieces - 9-Apr-25.

Word counts were determined for each page of Berakhot, with a threshold of 450 words used as a proxy to distinguish aggadic content from halachic material.

The bar charts were all generated using Python with the matplotlib plotting library, with manual annotation of significant thematic content based on the titles of my previous written work on the identified high-density sections.

E.B. note: This etymology is incorrect. Although the words share the same root (i.e. shoresh, from a linguistics perspective), 'Haggadah' isn’t directly connected to the broader literary category of 'aggadah'. Rather it’s a reference to the biblical verse, that’s understood the be the sources of the obligation for recounting the Exodus story of Seder night. .

See Hebrew Wiktionary “הגדה“, my translation, with slight adjustments:

Something a person recounts or tells to another person; a story one person tells another.

Specifically: the things parents are commanded to tell their children on Passover night, which include the story of the Exodus from Egypt ("The Passover Haggadah").

Etymology

A verbal noun from the root higid (to tell).

Some interpret it as deriving from the Aramaic neged (נגד), meaning "to draw" or "pull," based on midrashic explanations that these words "draw the heart" of the listener. (For example, [see] the Arukh by Nathan of Rome.)

There are wordplays on this root as well:

"As it is written, 'And Moses told [vayaged]' - words that draw a person's heart (מושכין לבו של אדם) like aggadah" (Babylonian Talmud, Shabbat 87a)

"'All supports (משען) of water' - these are the masters of aggadah (בעלי אגדה), who draw a person’s heart (מושכין לבו של אדם) like water, through aggadah" (Babylonian Talmud, Chagigah 14a), among others.

In the context of Passover, the commandment to recount the Exodus is found in the verse:

"And you shall tell (הגדת) your child on that day, saying:

It is because of this that YHWH did for me

when I came out of Egypt" (Exodus 13:8).

From here, the fulfillment of this commandment is called Haggadah, and the content of that retelling is also referred to as Haggadah.

As an aside, see the linguistic note regarding the interchangeability of the terms ‘aggadah’/’haggadah’ in Hebrew Wikipedia, “הגדה של פסח“, section “ביאורים“, note A, my translation:

[…] Dr. Gabriel Birnbaum notes:

"There is no difference between aggadah and haggadah except for a change in form, with no difference in meaning.

That was originally the case, though over time the form aggadah became dominant and pushed aside haggadah."

Presumably ‘haggadah’ is the Hebrew form, while ‘aggadah’ is the more Aramaic form.