The Densest Daf - Which Page of the Talmud Contains the Most Text? A Word Count Analysis That Definitively Identifies the Talmud’s Wordiest Pages

I'm excited to announce that I'll be giving a talk in two months (June 10, 2025) at a major academic conference, on the topic of "AI-Assisted Editing and Analysis of Rabbinic Texts – The Role of Generative AI in the Digital Age”. At the conference “The Israeli International Conference on Digital Humanities and Social Sciences”, hosted at the Open University campus in Raanana.1

Today, I’m excited to share the results of a digital humanities scripting project that provides a definitive answer to a question I first posed a year and a half ago: Which page of the Talmud contains the most words?

By “page of the Talmud,” I mean the standard printed format—tzurat hadaf—that has defined Talmudic pagination for the past 500 years, beginning with the 16th century Bomberg-Venice edition.2

What I find most compelling is the heuristic potential of this metric: word density reveals something meaningful. Aggadic pages consistently have higher-than-average word counts, due to the relative absence of Tosafot.

Conversely, halakhic sugyot consistently show lower word counts per page, as they are accompanied by a larger amount of Tosafot commentary. So using this computational analysis of word counts as a robust proxy for identifying aggadic material.3

Outline

Digital Tools for Ancient Texts

What We Found

Top 10 pages by word count

Patterns and Observations

What Berakhot 32a Contains

Summary of the Sugya (Berakhot 32a:1–33)

The Intersection of Tradition and Technology

Output file

Possible Future analyses

Appendix - The 10 Least-dense pages by word count

Digital Tools for Classical Texts

The Talmud has been studied for over a millennium, but only in our generation have we gained the ability to analyze its entire corpus computationally. (On pre-computer word-counting of the Bible in classical rabbinic literature, see my previous piece.)

Thanks to Sefaria, the complete text of the Talmud is easily available through their API – a digital gateway that allows computers to access their database directly.4

Using this resource, I created a straightforward program that:5

Accessed each tractate of the Babylonian Talmud

Cataloged the total number of pages (approximately 5,434 amudim [=pages], each double-sided page makes up a daf [=folio]; my title “densest daf” is thus a misnomer, since I’m analyzing on the level of the page, not folio, but I couldn’t resist the pun and turn-of-phrase)

Downloaded the Hebrew text of each page

Counted the number of Hebrew words on each page

Sorted them from highest to lowest word count

What We Found

After processing the entire Talmud (which took about 11 minutes), a clear winner emerged:

Berakhot 32a contains 883 Hebrew words, making it the wordiest page in the Talmud.6

Top 10 pages by word count

Here are the top 10 pages by word count:

Berakhot 32a:7 883 words

Berakhot 7a:8 858 words

Berakhot 10a:9 856 words

Berakhot 58a:10 853 words

Keritot 5b:11 843 words

Berakhot 55b:12 836 words

Berakhot 10b:13 834 words

Bava Batra 16a:14 833 words

Berakhot 56b:15 827 words

Sanhedrin 108a:16 822 words

Patterns and Observations

Several fascinating patterns emerge from this data:

Berakhot Dominates: Six of the top ten wordiest pages come from Tractate Berakhot.17 The large amount of aggadah there is indeed relatively well-known.

Distribution Across the Talmud: While Berakhot is heavily represented at the top, other tractates like Sanhedrin, Gittin, and Bava Batra also appear in the top 20, showing that particularly word-dense pages exist throughout the Talmud.

What Berakhot 32a Contains

What makes Berakhot 32a so word-dense? This page contains rich discussions on prayer, including:18

Moses's intense prayer following the Golden Calf incident

The proper attitude and approach to prayer

A debate about whether study or prayer takes precedence

Several teachings from R’ Elazar about prayer methodology

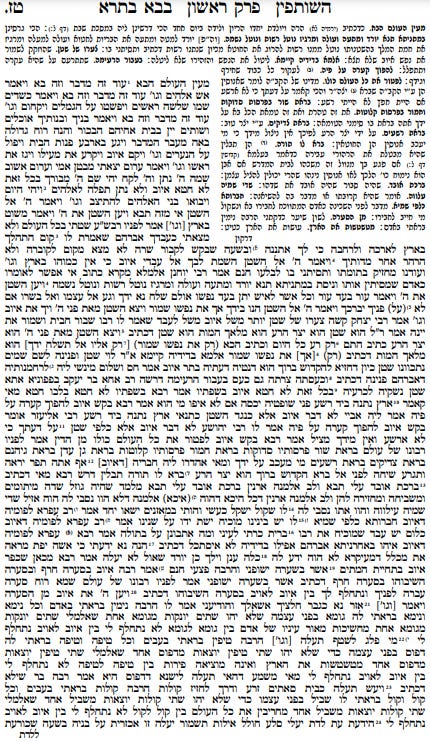

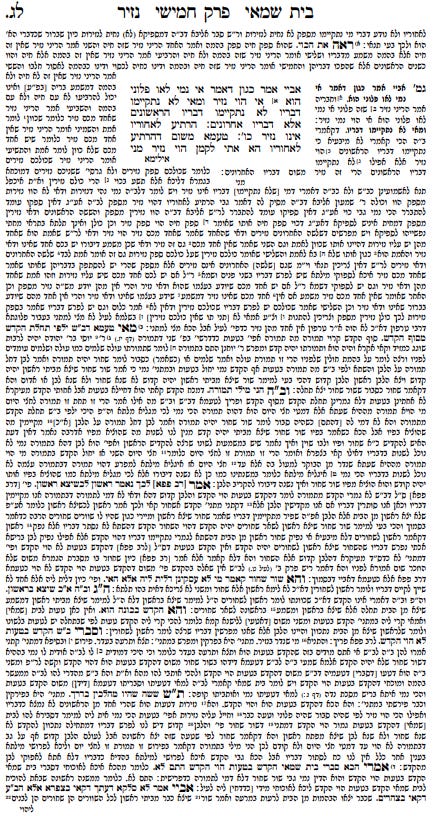

Berakhot 32a in the traditional tzurat hadaf, at the ‘Daf Yomi’ website (here), screenshot:

Output file

Excel file:19

Google sheet:

The Intersection of Tradition and Technology

This small experiment exemplifies how modern technology can provide new perspectives on classical texts. While computational analysis cannot replace traditional scholarship, it can complement it by revealing patterns that might be difficult to perceive through conventional study alone.

As we continue to bridge the worlds of traditional Talmudic scholarship and modern digital tools, we open new avenues for understanding our foundational texts. These approaches don't diminish the depth of traditional learning—they enhance it, offering additional dimensions of insight.

Possible Future analyses

This study of word count is just the beginning.20

Future analyses could examine:

Word frequency and distribution

Linguistic patterns across tractates

The correlation between word density and topic complexity

Changes in language patterns throughout the Talmud

Longest sugyot

Other heuristics for finding patterns21

By utilizing the capabilities of modern technology, we can continue to find new ways to understand and engage with our classic texts.

Appendix - The 10 Least-dense pages by word count

See footnote for a previous discussion of this question.22

Bava Kamma 77a:23 9 words

Yoma 56a:24 12 words

Zevachim 71a:25 17 words

Zevachim 61a:26 19 words

Nedarim 45b:27 21 words

Zevachim 51b: 23 words

Nedarim 40b: 33 words

Nedarim 2a: 34 words

Nazir 33a:28 38 words

Bekhorot 22b: 40 words

הכנס הישראלי הבין-לאומי למדעי הרוח והחברה הדיגיטליים

Description of the conference:

“The Israeli International Conference on Digital Humanities and Social Sciences 2025 explores how digital and computational tools are transforming scholarship in the humanities and social sciences.

By fostering interdisciplinary dialogue, the conference highlights innovative methods, raises new questions, and addresses pressing challenges in studying human culture and society.

This event serves as a vibrant platform for researchers and practitioners to share cutting-edge research leveraging digital and computational methods, examine various implications of digital scholarship, and build networks for interdisciplinary collaboration.

To register, go here.

Thanks to Prof. Menachem Katz for inviting me to present, and to all the organizers!

For more on Bomberg’s role in establishing this layout, and its prior and subsequent history, see my piece “Pixel”, cited in my recent piece here, f.2, with the bibliography cited there.

I’ve explored and confirmed this point—the strong correlation between above-average page word count and aggadic content—at length in a separate piece, which I plan to publish next: “A Computational Approach to Identifying and Mapping Aggadic Content in the Talmud: Word Count as a Robust Predictive Indicator” .

That piece will also include visualizations, especially focused on “clustering” of aggadic segments (i.e. aggadic sugyot):

“Case Study: Visualizing Aggadic Density in Tractates Berakhot and Shabbat — Bar Charts of High-Word-Count ‘Aggadic Islands’ with Annotations Based on Previous Work”

I’ve discussed various scripts accessing their API for fetching Talmud text. I plan to discuss some more of the technical aspects of the Sefaria API in regards to Talmud text. For now, I’d just like to note a confusing aspect of how Sefaria presents sections; one which AI assistants consistently get confused by, and I’ve therefore added to my custom instructions when working with AI assistants on relevant scripting:

Structure of Talmud text via Sefaria API:

- Each daf (2a, 2b, etc.) is split into numbered "sections" (=paragraphs. This splitting is original to ed. Steinsaltz, in the original printed edition, and is becoming standard; I use this citation consistently on this blog, and see my discussion of this in my piece “Pixel”, cited earlier).

- API returns full daf as a list: data['text'] and data['he'], where text[i] corresponds to section number i+1 on the printed daf.

For example, text[0] is the first paragraph on the daf (i.e., section 1), text[1] is section 2, and so on.

Each entry in text[i] and he[i] corresponds to a logical paragraph of the Talmud on that daf.

> ⚠️ Section-level refs like `Berakhot.2b.19` or `Berakhot.2b.19-2b.21` are ignored by the Sefaria API and return the entire daf.

Key Limitation

- The Sefaria API ignores section-level refs like `Berakhot.2b.19-2b.21`.

- These only work on the Sefaria website UI, not in Sefaria API queries.

Workaround

1. Fetch full daf:

'https://www.sefaria.org/api/texts/Berakhot.2b'2. Slice desired sections in additional processing:

start, end = 18, 21

english = data['text'][start:end+1]

hebrew = data['he'][start:end+1]As an aside, I worked with the current best AI LLM model for coding (Claude 3.7 extended thinking; this model came out around a month-and-a-half ago) to develop the script.

As I expected, the final working script ended up being quite straightforward, totalling just over 100 lines of Python code, you can see the final script here:

This was previously pointed out at the forum Mi Yodeya: “What page of the Babylonian Talmud has the most words?” (~2023).

See link to tzurat hadaf and screenshot later in this piece.

Screenshot of tzurat hadaf:

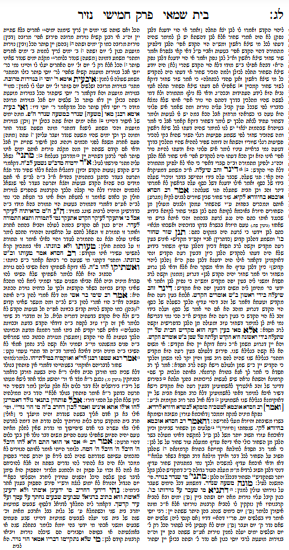

Screenshot of tzurat hadaf:

Screenshot of tzurat hadaf:

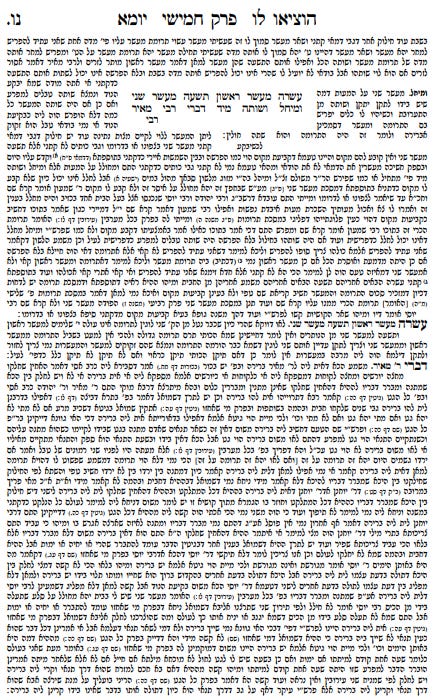

Screenshot of tzurat hadaf:

Screenshot of tzurat hadaf:

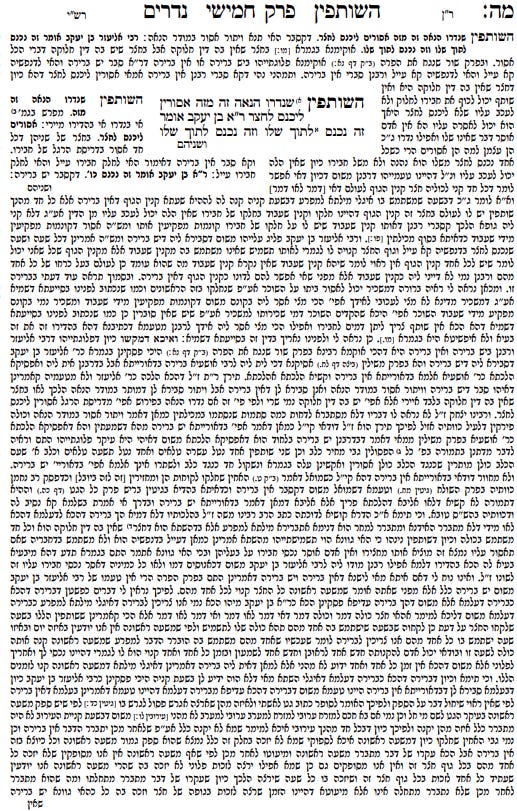

Screenshot of tzurat hadaf:

Screenshot of tzurat hadaf:

Screenshot of tzurat hadaf:

Screenshot of tzurat hadaf:

See now my charts visualizing this (bar charts and heat maps), for tractates Berakhot and Shabbat, in my follow-up piece “A Computational Approach to Identifying and Mapping Aggadic Content in the Talmud: Word Count as a Robust Proxy Indicator”.

As an aside, I’ve continued to improve the tooling all along the chain. See my extensive discussion in my recent two-part series (two days ago and yesterday): “ChavrutAI Web App in Progress: Advancing the Vision of a More Accessible Talmud“, final part here.

I now have a Google Colab (Jupyter) notebook that will allow the user to request text in either by dropdown or URL (the notebook is available here: v2 Sefaria Talmud Text Fetcher and processor - by dropdown or URL).

The script also does other post-processing, most of which is the same as described in the readme at my Github repo here: https://github.com/EzraBrand/talmud

I have a custom project in Chatgpt4 that I use for this (see my custom instruction in that series, Part 2, yesterday’s piece).

When I put in that page there (Hebrew, with Steinsaltz translation and interpretation), this is what I get:

Summary of the Sugya (Berakhot 32a:1–33)

Concepts and Takeaways:

Divine Responsibility in Human Sin: The sugya explores to what extent God causes or enables human sin, softening blame on Israel by highlighting divine involvement in their choices.

Radical Theological Anthropology: The depictions of Moses “grabbing” God or causing Him to change His mind suggest a dynamic, relational theology where human intercession matters.

Power of Prayer and Protest: Moses’ bold advocacy for Israel, even against divine wrath, is a model of courageous leadership, challenging God on moral and rhetorical grounds.

Wealth and Spiritual Decline: A recurring motif is that material abundance leads to moral downfall, supported by analogies, folk sayings, and scriptural prooftexts.

Rhetorical Strategy in Prayer: The Talmud emphasizes the importance of structuring prayer with praise before request, as modeled by Moses, underscoring prayer as both theological and rhetorical performance.

Summary (numbered bullet points):

God’s Role in Human Sin: The Talmud cites Micah 4:6 where God says, “those with whom I have dealt wickedly,” implying divine responsibility for Israel’s wrongdoing.

Three Verses that Sustain Israel: R' Ḥama bar R' Ḥanina says Israel could not endure divine judgment without three verses that show God influences human actions: (1) Micah 4:6, (2) Jeremiah 18:6 (Israel as clay in the potter’s hand), (3) Ezekiel 36:26 (God replaces the heart of stone).

A Fourth Verse: Rav Pappa adds Ezekiel 36:27, in which God causes people to follow His statutes, reinforcing divine influence over human behavior.

Moses’ Boldness with God: R' Elazar interprets Numbers 11:2 as implying Moses spoke impertinently to God by reading “to YHWH” as “against YHWH,” based on variant pronunciation traditions.

“Di Zahav” and the Golden Calf: The school of R' Yannai interprets “Di Zahav” as Moses blaming Israel’s wealth for their sin. Analogies include: a lion only roaring when full, a cow kicking after being fed well, and a son led to sin after being indulged and placed outside a brothel.

Prosperity Leads to Sin: Multiple verses and proverbs are cited to show that overabundance leads to arrogance and sin (e.g., Deut. 8:14, Hoshea 13:6, Deut. 31:20, Deut. 32:15).

God Agrees with Moses: R' Shmuel bar Naḥmani says Hosea 2:10 shows God acknowledged Moses' argument that wealth led to the Golden Calf.

“Go Down” Means Fall from Greatness: R' Elazar interprets God's command to Moses “go down” (Exod. 32:7) as meaning he should descend from his prophetic greatness due to Israel's sin.

Moses Realizes His Power in Prayer: Upon hearing “Leave Me,” Moses realizes God is giving him a chance to intercede and immediately begins to pray.

Parable of King and Son: A parable illustrates that Moses acted when he saw God hinting that the outcome depended on him, as a king’s friend saves a son from punishment.

Moses “Grabs” God in Prayer: R' Abbahu says Moses seized God like someone grabbing a friend’s garment, demanding forgiveness.

Moses Rejects Personal Greatness: In response to God's offer to make a new nation from him, Moses argues that if the merit of the three patriarchs wasn’t enough, how could his alone suffice?

Concern for Reputation and Leadership: Moses refuses to abandon the people because it would appear self-serving and shameful to his ancestors.

“Vayḥal” – Multiple Meanings: The word “vayḥal” (Exod. 32:11) is interpreted in various ways:

Moses exhausted himself in prayer (R' Elazar).

He annulled God's vow (Rava).

He risked his life (Shmuel).

He invoked divine mercy (Rav Yitzḥak).

He declared such an act sacrilegious (the Rabbis).

He prayed until he got a fever (“fire of the bones” – R' Eliezer the Great).

Eternality of God's Oath: Moses invokes God’s eternal name (Exod. 32:13) to prove the oath to the patriarchs must remain valid.

"Of which I have spoken": The odd phrase in Exod. 32:13 is interpreted by R' Elazar and R' Shmuel bar Naḥmani as Moses including God's words in his own speech or quoting divine language for rhetorical effect.

Avoiding the Appearance of Divine Weakness: Moses worries that failure to bring Israel into the land will appear to the nations as God's weakness (Num. 14:16). God counters, but Moses insists others might still say God can defeat one king, but not thirty-one.

God Concedes to Moses: Num. 14:20 (“I have forgiven according to your word”) is seen as God conceding to Moses' argument. The Sages add that nations will later say the same.

“You Gave Me Life”: Rava interprets Num. 14:21 to mean God told Moses, “You have revived Me with your words.”

Prayer Structure – Praise Before Request: R' Simlai teaches from Moses' example that one should praise God before making personal requests (Deut. 3:23–25).

Appendix - In-depth Analysis of Talmud Word Count Distribution (by Claude AI)

Important note: This analysis was generated by Claude AI. I haven’t reviewed it closely, so each data point should be treated with caution and independently verified/confirmed.

Overview Statistics

Total Pages Analyzed: 5,347 pages

Total Hebrew Words: 1,859,952 (on this word count of the Talmud Bavli, see also my previous pieces)

Average Words Per Page: 348

Median Words Per Page: 338

Range: 9 to 883 words

Record Holders

Most Words

Berakhot 32a: 883 words

Berakhot 7a: 858 words

Berakhot 10a: 856 words

Berakhot 58a: 853 words

Keritot 5b: 843 words

Fewest Words

Bava Kamma 77a: 9 words

Yoma 56a: 12 words

Zevachim 71a: 17 words

Zevachim 61a: 19 words

Nedarim 45b: 21 words

Tractate Analysis

Densest Tractates (By Average Word Count)

Berakhot: 568 words per page

Horayot: 517 words per page

Keritot: 498 words per page

Megillah: 476 words per page

Sanhedrin: 458 words per page

Sparsest Tractates (By Average Word Count)

Nedarim: 195 words per page (due to verbose commentaries of Ran and others)

Meilah: 203 words per page

Nazir: 222 words per page

Zevachim: 293 words per page

Tamid: 295 words per page

Tractates with Highest Variability

Chagigah: 43.37% coefficient of variation

Nedarim: 43.30% coefficient of variation

Yoma: 41.85% coefficient of variation

Bava (Kamma/Metzia/Batra): 39.81% coefficient of variation

Makkot: 37.89% coefficient of variation

Distribution Patterns

Overall Word Count Distribution

0-100 words: 1.91% of pages (102 pages)

100-200 words: 10.88% of pages (582 pages)

200-300 words: 24.95% of pages (1,334 pages)

300-400 words: 29.94% of pages (1,601 pages) - Most common range

400-500 words: 19.60% of pages (1,048 pages)

500-600 words: 8.29% of pages (443 pages)

600-700 words: 3.18% of pages (170 pages)

700-800 words: 1.07% of pages (57 pages)

800-900 words: 0.19% of pages (10 pages)

A-Side vs B-Side Comparison

A-Side Pages: 2,954 pages (55.2% of total)

Average: 344 words per page

Highest: 883 words (Berakhot 32a)

Lowest: 9 words (Bava Kamma 77a)

B-Side Pages: 2,121 pages (39.7% of total)

Average: 352 words per page

Highest: 843 words (Keritot 5b)

Lowest: 21 words (Nedarim 45b)

Interestingly, B-sides average about 8 more words per page than A-sides.

Statistical Outliers

Pages More Than 2 Standard Deviations from Mean

Total outliers: 240 pages (4.5% of all pages)

Upper threshold: 617 words

Lower threshold: 79 words

Tractates with Most Outliers

Berakhot: 50 outliers (all high outliers) - 40% of its pages are outliers!

Sanhedrin: 33 outliers (all high outliers) - 14.7% of its pages (likely primarily due to the aggadic Perek Chelek)

Bava Kamma/Metzia/Batra: 23 outliers (12 high, 11 low) - 2.8% of its pages

Sotah: 11 outliers (9 high, 2 low) - 11.5% of its pages

Nedarim: 11 outliers (all low outliers) - 6.1% of its pages

Focus on Berakhot

Berakhot stands out dramatically in this analysis:

Average: 568 words per page (63% higher than the Talmud average)

Median: 558 words

Range: 235 to 883 words

No pages below 200 words

42.4% of pages have more than 600 words

5.6% of pages have more than 800 words

Most common range: 500-600 words (24.8% of pages)

First Half vs. Second Half Differences

Some tractates show dramatic differences in word density between their first and second halves:

Shevuot: Second half is 31.96% more word-dense than the first half

Gittin: Second half is 24.64% more word-dense than the first half

Chagigah: First half is 22.9% more word-dense than the second half

This suggests thematic or structural shifts within tractates, possibly reflecting transitions between halachic and aggadic material.

Dramatic Page-to-Page Transitions

The most dramatic shift occurs between Temurah 16a and 16b, where the word count drops by 556 words (82.01% decrease). Other notable transitions:

Yoma 37b to 38a: +520 words (409.45% increase)

Yoma 35a to 35b: +452 words (602.67% increase)

These extreme transitions presumably represent shifts between heavily commentated sections (fewer words on the page) and text-dense sections.

Order-Specific Patterns

When analyzed by Talmudic Order (Seder):

Zeraim (represented only by Berakhot): 568.39 words/page

Nezikin: 352.58 words/page

Moed: 357.15 words/page

Kodashim: 334.92 words/page

Nashim: 318.68 words/page

This reveals tha pages in Nezikin and Moed orders tend to be wordier than Kodashim and Nashim, presumably due to a greater amount of aggadic discussions.

Tractate Irregularity

The most internally inconsistent tractates (highest coefficient of variation):

Bava Batra: 48.23% coefficient of variation

Chagigah: 43.37%

Nedarim: 43.30%

Yoma: 41.85%

This inconsistency suggests these tractates contain the most diverse mixture of content types or commentary styles.

"Twin Pages" Phenomenon

Remarkably, some word counts occur repeatedly throughout the Talmud. For example:

27 different pages contain exactly 307 words

27 pages contain exactly 324 words

26 pages contain exactly 304 words

This unexpected pattern presumably reflect standardization in the typesetting process of the Bomberg edition.

A-side to B-side Transitions

Contrary to what might be expected, there's virtually no systematic difference when moving from A-side to B-side of the same folio (average change is just -0.71 words).

Word Count Percentiles

10th percentile: 182 words

Median (50th): 338 words

90th percentile: 521 words

This distribution helps contextualize just how exceptional those 800+ word pages really are.

Other Notable Findings

The Berakhot Phenomenon: Berakhot is dramatically denser than other tractates, with pages averaging 63% more words than the Talmud average.

Word Distribution Pattern: The overall Talmud follows a roughly normal distribution centered around 300-400 words, but with a positive skew (longer tail on the high end).

B-Side Tendency: B-sides of folios tend to have slightly more words than A-sides (about 2.2% more).

Extreme Variability: Some tractates like Chagigah, Nedarim, and Yoma show tremendous variability in word count, suggesting inconsistent density throughout these tractates.

Extremely Short Pages: Several pages have fewer than 20 words (likely primarily due to large Tosafot commentary).

Order Matters: The first tractate (Berakhot) is dramatically denser than the rest of the Talmud.

Another heuristic I’m especially interested in for labeling Talmudic sugyot as aggadah vs. halacha is the ratio of bolded text in the English translation/commentary of ed. Steinsaltz. I’ve started looking into this and plan to explore it further in a future piece.

See the discussion at the forum Mi Yodeya: “Shortest amud or daf in Shas?” (~2019). The highest-rated answer there is:

The shortest amud is Nazir 33b which contains precisely zero words of gemara.

Screenshot of tzurat hadaf:

(My script filtered out all responses of 0, for technical reasons.)

The next highest-rated answer:

1st place: Bava Kama 77a has 9 words of gemara on it and is thus the shortest amud with words of gemara on it in shas. The Tosfos that fills the page is very VERY big.

A close 2nd place is Yoma 56a with 12 words.

The Shortest Daf in shas that has words on both pages is Nedarim 45a-b which has 69 words (not including Hadran Alach).

Nedarim 45b happens to also be the 3rd shortest Amud with 20 words.

Though (@JoelK mentioned it with regards to shortest amud but was able to verify it's the shortest daf of gemara) the shortest daf which has only one page with words from the gemara is Nazir 33a-b which has 38 words.

The assertions regarding 1st and 2nd place are correct, as I’ve verified. The assertion regarding 3rd place—”Nedarim 45b happens to also be the 3rd shortest Amud with 20 words”—isn’t fully correct. As I listed in the main piece, Zevachim 71a (17 words) and Zevachim 61a (19 words) come before it, at 3rd and 4th place.

Screenshot of tzurat hadaf:

Screenshot of tzurat hadaf:

Screenshot of tzurat hadaf:

Screenshot of tzurat hadaf:

Screenshot of tzurat hadaf:

Screenshot of tzurat hadaf:

This looks very cool but I have a few questions/comments:

1. Can you explain why your previous analysis identified Sanhedrin 108a?

2. I don't think the Sefaria text has any contractions (even simple ones like א"ר for אמר רב) but it does contain in-line citations of biblical verses, which will result in overcounting the words on folios that have more of these citations.

More generally: I guess you'll get into this in the next post, but I don't really understand why you needed a good indicator for identifying aggadic texts, when the Ein Yaakov did that already? I mean, it's not perfect (and there's some grey area between aggadah and halakha anyways) but I would imagine that it is more robust of an indicator than any other? Have you done a comparison between these correlative indeces vs a simple check of whether the talmudic passage appears in Ein Yaakov?