Pt2 Etymologies and Identifications of Biblical Figures in the Talmud: A Literary Analysis

This is the second and final part of a two-part series. Part 1 is here; the outline of the series can be found at Part 1.

The Patronym as Commentary on Character

The Talmud extends its interpretive methods to patronymics as well.

Caleb’s Father: Jephunneh as Description (Temurah 16a)

וכלב —

בן קנז הוא? והלא “כלב בן יפונה” הוא!

מאי “יפונה”? שפנה מעצת מרגלים.

And Caleb —

was he the son of Kenaz? Wasn’t he Caleb, son of Jephunneh (Joshua 15:13)?

What [does the word] Jephunneh [mean]? That he turned [pana, away from] from the advice of the spies [and did not join with them]

“Jephunneh” is not Caleb’s father’s name but a description of Caleb himself. The patronym is transformed into an epithet: Caleb is the one who “turned away” from evil counsel.

Mordecai’s Patronyms: Praise Encoded (Megillah 12b)

תנא:

כולן על שמו נקראו:

“בן יאיר” — בן שהאיר עיניהם של ישראל בתפלתו.

“בן שמעי” — בן ששמע אל תפלתו.

“בן קיש” — שהקיש על שערי רחמים ונפתחו לו

A baraita states:

All of them are names by which Mordecai was called:

“The son of Jair” — [because he was] the son who enlightened [he’ir] the eyes of all the Jewish people with his prayers.

“The son of Shimei” — [because he was] the son whom God heard [shama] his prayers.

“The son of Kish” — [because] he knocked [hikish] on the gates of mercy and they were opened to him.

Mordecai’s entire genealogy becomes praise: he enlightens, he is heard, he knocks and is answered. The historical ancestors Jair, Shimei, and Kish are transformed into descriptions of Mordecai’s own piety.

The Righteous

Divine Names: Samson and the Theophoric Element (Sotah 10a)

Some etymologies connect biblical figures directly to divine attributes:

ואמר רבי יוחנן:

שמשון על שמו של הקדוש ברוך הוא נקרא,

שנאמר: “כי שמש ומגן ה׳ אלהים וגו׳”

R’ Yoḥanan says:

Samson [Shimshon] is called by the name of God,

as it is stated: “For YHWH God is a sun [shemesh] and a shield” (Psalms 84:12).

This remarkable statement places Samson in a quasi-divine category: his very name participates in one of God’s biblical epithets.

Palti Becomes Paltiel (Sanhedrin 19b)

כתיב “פלטי”

וכתיב “פלטיאל”

אמר רבי יוחנן:

פלטי שמו,

ולמה נקרא שמו פלטיאל? שפלטו אל מן העבירה.

It is written “Palti” (I Samuel 25:44),

and it is written “Paltiel” (II Samuel 3:15).

R’ Yoḥanan says:

Palti was his [real] name.

Why was his name called Paltiel? [To teach] that God [El] saved him [pelato] from sin.

The theophoric element (-el, “God”) is added to Palti’s name as a reward for his righteousness in not touching Michal during her forced marriage to him.1 The name change is a narrative of divine approval.

The Wicked Reversal: Etymology for Villains

Negative figures receive etymologies that encode their sins. The pattern is the inverse of heroic naming: where the righteous receive names that reflect their virtues, the wicked receive names that brand their vices.

Goliath: Brazenness Before God (Sotah 42b)

גלית —

אמר רבי יוחנן:

שעמד בגילוי פנים לפני הקדוש ברוך הוא

Goliath —

R’ Yoḥanan says:

[The name indicates] that he stood before God with brazenness [gilui panim].

The giant’s name becomes an accusation: Goliath was not merely large but spiritually brazen: he stood “with uncovered face”2 before God, lacking proper reverence.

Cozbi: Deception and Destruction (Sanhedrin 82b)

אמר רב ששת:

לא “כזבי” שמה,

אלא “שוילנאי בת צור” שמה

ולמה נקרא שמה “כזבי”?

שכזבה באביה

דבר אחר:

“כזבי” – שאמרה לאביה: “כוס בי עם זה”.

Rav Sheshet says:

Cozbi was not her [given] name;

rather, “Shevilnai, daughter of Zur” was her [real] name.

Why was she called Cozbi?

Because she distorted [kizzeva, the instructions of] her father.

Alternatively:

[She was called] Cozbi [because] she said to her father: “Slaughter [kos] this people through me [bi].”

Both etymologies are damning: she either lied to her father or volunteered herself as a weapon against Israel. The name Cozbi encodes either deception or murderousness.

Nahbi son of Vophsi: The Spy’s Condemnation (Sotah 34b)

אמר רבי יוחנן:

אף אנו נאמר:

“נחבי בן ופסי”,

“נחבי” — שהחביא דבריו של הקדוש ברוך הוא.

“ופסי” — שפיסע על מדותיו של הקדוש ברוך הוא.

R’ Yoḥanan says:

We can also say [an interpretation of the name]

“Nahbi the son of Vophsi”:

[He is called] Nahbi as he concealed [heḥbi] the statement of God [that the land of Israel is good]

[He is called] Vophsi as he stomped [pisse’a] on the attributes of God.

The spy’s very name encodes his crime: concealing divine promise and trampling divine attributes.

Korah’s Cohorts (Sanhedrin 109b)

The same passage as cited earlier re Korah,3 extends the technique to Korah’s fellow rebels:

“דתן” – שעבר על דת אל,

“אבירם” – שאיבר עצמו מעשות תשובה,

“ואון” – שישב באנינות,

“פלת” – שנעשו לו פלאות,

“בן ראובן” – בן שראה והבין.

Translation:

“Dathan” — one who violated the precepts [dat] of God.

“Abiram” — one who braced [iber] himself from repenting.

“And On” — indicates one who sat in acute mourning [aninut, over the sin that he committed, and he repented]

“Peleth” — is one for whom wonders [pelaot] were performed.

“Son of Reuben” — a son who saw and understood [ra’a ve-hevin, the nature of what was transpiring and repented]

Note the subtle narrative embedded in these etymologies: On and his father Peleth are treated positively (mourning, wonders, understanding), reflecting the midrashic tradition that On’s wife saved him from participating in the rebellion.

The Triple Etymology: Delilah (Sotah 9b)

תניא,

רבי אומר:

אילמלא לא נקרא שמה “דלילה” —

ראויה היתה שתקרא דלילה:

דילדלה את כחו,

דילדלה את לבו,

דילדלה את מעשיו.

A baraita [states]:

R’ Yehuda HaNasi says:

Even if she had not been called by the name Delilah —

it would have been fitting that she be called Delilah, [for]:

she weakened [dildela] his strength,

she weakened his heart,

and she weakened his deeds, thereby decreasing his merits.

The rhetorical structure is striking: the name is so fitting that it would have been appropriate even if it weren’t already hers.

Jeroboam: The Paradigm of Wickedness (Sanhedrin 101b)

A distinctive pattern involves providing multiple etymologies for a single name, introduced by the formula “another interpretation”.4

The arch-sinner Jeroboam receives an unusually elaborate treatment with three alternative etymologies followed by interpretation of his patronym:

תנו רבנן:

ירבעם – שריבע עם

דבר אחר: ירבעם – שעשה מריבה בעם

דבר אחר: ירבעם – שעשה מריבה בין ישראל לאביהם שבשמים

בן נבט – בן שניבט ולא ראה.

A baraita states:

Jeroboam [Yorovam] — [is an abbreviation for one who] assaulted5 [the Jewish] people [am].

Alternatively: Yorovam — [is an abbreviation for one who] engendered strife within the people [meriva ba’am, causing the schism between the kingdoms of Judea and Israel].

Alternatively: Yorovam — [is an abbreviation for one who] engendered strife [meriva] between the Jews and their Heavenly Father [=God, as Jeroboam instituted the worship of the golden calves]

Son of Nebat — [because] he is the son who looked [nibat, in an effort to assess the situation] but did not see [the situation accurately]

The three etymologies trace an escalating arc: from debasing the people, to dividing them, to separating them from God. The patronym “son of Nebat” adds the dimension of failed vision—Jeroboam saw ambition for kingship but failed to perceive its ultimate cost.

Benjamin’s Sons: Joseph Encoded (Sotah 36b)

Benjamin’s ten sons receive names that all refer to his absent brother Joseph:

“בלע” — שנבלע בין האומות,

“ובכר” — בכור לאמו היה,

“ואשבל” — ששבאו אל,

“גרא” — שגר באכסניות,

“ונעמן” — שנעים ביותר,

“אחי וראש” — אחי הוא וראשי הוא,

“מפים וחפים” — הוא לא ראה בחופתי ואני לא ראיתי בחופתו,

“וארד” — שירד לבין אומות העולם. איכא דאמרי: “וארד” — שפניו דומין לוורד.

Bela — [after Joseph,] who was swallowed [nivla] among the nations.

Becher — [because Joseph] was the firstborn [bekhor] of his mother [=Rachel]

Ashbel — because God sent [Joseph] into captivity [sheva’o El].

Gera — [after Joseph,] who dwelled [gar] in a foreign land (אכסניות - xenia)

Naaman — [because Joseph was] extremely pleasing [na’im].

Ehi and Rosh — “He is my brother [aḥi] and my leader [roshi].”

Muppim and Huppim — “He did not see my wedding canopy [ḥuppa] and I did not see his.”

Ard — [after Joseph, who] descended [yarad] to the [non-Jewish] nations. Some say: Ard [means that Joseph’s] face was similar to a rose [vered].

Every son’s name is a reference to Joseph’s history and virtues.

The Giants: Physical Etymology (Yoma 10a)

The three Anakim giants receive names interpreted through their physical impact:

אחימן — מיומן שבאחים,

ששי — שמשים את הארץ כשחיתות,

תלמי — שמשים את הארץ תלמים תלמים

Ahiman [was so called because he was] the greatest and most skillful [meyuman] of his brothers.

Sheshai [was so called because] he renders the ground like pits [sheḥitot, with his strides]

Talmai [was so called because] he renders the ground filled with furrows [telamim, with his strides]

The etymology pushes the giants’ enormity to extremes: their very footsteps reshape the landscape.

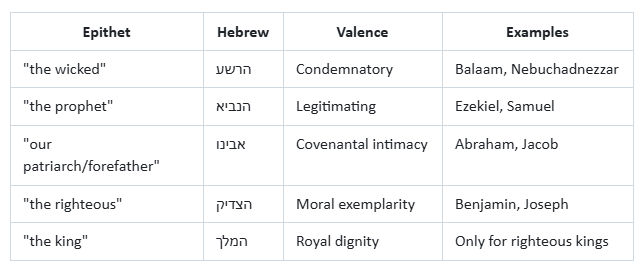

Appendix - The Epithet System: Moral Classification Through Titles

The Restriction of “The King” (המלך)

I note6 that “the king” (המלך - ha-melekh) is “generally only used in the Talmud for righteous kings, such as King Hezekiah, King David, and King Solomon” is particularly significant. Foreign or wicked kings receive the formula “X, king of [place]”:

“Eglon, king of Moab” (עגלון מלך מואב)

“Ḥiram, king of Tyre”

“Mesha, king of Moab”

“Sennacherib, king of Assyria”

“Shishak, king of Egypt”

The distinction seems to be consistent: המלך (”the king”) implies legitimate royal dignity, while מלך פלוני (”king of X”) is merely geographical designation. Even Israelite kings who are evaluated negatively lose the definite article: they ruled, but they were not truly “the king.”

“The Wicked” as Permanent Marker

Figures like “Balaam the wicked” (בלעם הרשע) and “the wicked Nebuchadnezzar” receive their epithet as a kind of permanent brand.

Disambiguation Through Epithet

I theorize that some epithets serve to distinguish biblical figures from Talmudic contemporaries:

“Samuel of Ramah” (שמואל הרמתי) — distinguishes from the Amora Shmuel

“Hezekiah, king of Judea” — distinguishes from the Talmudic figure Hezekiah

“Joshua, son of Nun” — distinguishes from other Joshuas

“Eliezer, servant of Abraham” — distinguishes from R’ Eliezer

I note that the ed. Steinsaltz translation helpfully uses archaic transliterations for biblical names (Samuel, Isaac, Jacob) while using modern transliterations for Talmudic names (Shmuel, Yitzhak, Ya’akov). A related differentiation may be built into the Talmud’s own epithet system.

In general, see my discussion in “Godly Nomenclature: Theophoric Names in the Hebrew Bible“.

גילוי פנים - a common Talmudic idiom.

In Part 1, section “Korah’s Full Genealogy as Moral Cipher (Sanhedrin 109b)“.

דבר אחר - literally: “another thing”.

riba - literally: “fucked, sexually assaulted”.

While vulgar in English, “fucked” is the closest and most precise translation of this word. Compare my discussion of transitive Hebrew words for sex, and the lack of non-vulgar English equivalents, in an extended note in “ “Today is Yom Kippur, and several virgins had sex in Neharde’a”: Anecdotes of Sinning on Yom Kippur (Yoma 19b-20a)“.

In the piece that this piece is based on (as noted in the initial footnote in Part 1), “Biblical Figures in the Talmud: Counts, Contexts, and Index“, section “Notes re eponymous ancestors, epithets, and etymologies“, and various footnotes there.