Pt2 Revealing the Order: Literary Structure and Rhetoric in the Mishnah

This is the second part of a three-part series, based on my research on literary structure in the Mishnah. Part 1 is here; the outline of the series can be found at Part 1.

Part 2: Cataloging Complexity – The Diverse Forms of Mishnaic Lists

Introduction to Part 2: Beyond Simple Lists

In Part 1 of this series, we began to peel back the layers of Mishnaic composition, seeing how visual formatting—my approach of using tables and structured lists—can illuminate the underlying order in texts often perceived as dense.

We focused on foundational examples, particularly hierarchical lists of impurity and sanctity from Tractate Kelim, and how simple enumerations can carry significant legal principles.

Now, in Part 2, we go deeper into the Mishnah's repertoire. The Mishnaic editor utilized lists in remarkably diverse and sophisticated ways, extending far beyond simple enumeration or straightforward hierarchies.

We will explore lists structured around numerical ranges, intricate comparisons, and those contingent upon specific conditions or timing.

As I’ve aimed to show in my work, organizing these lists visually allows readers to "quickly grasp the relationships between items, hierarchies, and categories" (Mishnah: Visualizing Literary Structure, p. 1), revealing the precision and pedagogical clarity embedded in Mishnaic discourse.

The common thread remains: even as the complexity of the content increases, clear visual presentation of the inherent structure makes the Mishnah more accessible and its internal logic more transparent.

Numerical and Range-Based Organization

The Mishnah often employs numbers not just for counting items, but for establishing legal parameters, ranges, and minimums/maximums.

My formatted tables help to make these numerical stipulations clear and comparable.

Case Study: Arakhin 2:1b-6a – "A List of 14 Number Ranges in Temple Services, Purity Laws, and Religious Observances"

This section of tractate Arakhin is a prime example of how the Mishnah uses a consistent formula to define ranges. The pattern often follows the structure:

"אין... פחות מ... ולא יתר על..."

no fewer than X and no more than Y

Here is my table, original Hebrew, and my translation (from Mishnah: Visualizing Literary Structure, p. 16-19):

Original Hebrew:

My translation:

There is no valuation (ערכין) less than 1 sela, and no more than 50 sela.

In [the case of] ‘petah for one who erred’,1 the least is 7, and the most is 17.

In [cases of] nega’im, there is no [period of quarantine] less than 1 week, and no more than 3 weeks.

[ ...and so on for all 14 items, following my translation on p.18-19 of the PDF...]

There were no fewer than 12 Levites standing on the platform, and they could be increased indefinitely.

This tabular format allows for quick comparison across diverse legal areas, all unified by the Mishnah's use of defined numerical ranges.

The "Minimum" and "Maximum" columns clearly delineate the boundaries set by the Mishnaic editor.

Case Study: Arakhin 3:1-5a – "A List of 5 Fixed and Variable Financial Penalties and Costs"

Another interesting numerical structure in tractate Arakhin involves contrasting fixed sums with variable, market-based valuations.

My table (from Mishnah: Visualizing Literary Structure, p. 19-21) highlights this distinction; in the Mishnah, it’s framed by the following recurring formula:

"יש ב... להקל ולהחמיר"

There are [cases] in X [where the law is] lenient and stringent.2

Table:

Original Hebrew:

My translation:

There are cases in vows of valuation (arakhin) where the law is lenient and stringent.

How so?

Whether one vows the valuation of the most beautiful person in Israel or the ugliest person, they give 50 shekels.

But if one says, "I take upon myself the monetary worth," they give the actual value of the person.

In fields dedicated to the Temple (שדה אחוזה), both lenient and stringent laws apply.

How so?

Whether one dedicates a field in the surrounding sands (חולת המחוז) or dedicates a field in the orchards of Sebastia (סבסטי), they give the amount for sowing a homer of barley seeds: 50 silver shekels.

But in the case of a purchased field (שדה מקנה), they give its actual value.

[ ...and so on, following my translation on p.21-22 of the PDF...]

Presenting this information in a table with "Fixed" and "Variable" columns makes the Mishnaic legal reasoning transparent.

The structure highlights how, for certain consecrated valuations or damages, a standard sum applies regardless of market fluctuations or individual characteristics, while in parallel situations, the actual monetary worth is the determining factor.

Comparative and Contrastive Lists

A significant rhetorical and legal technique in the Mishnah is the use of comparative lists, employing the formula:

The only difference between X and Y is Z3

This structure precisely isolates the distinguishing legal factor between two otherwise similar items or situations.

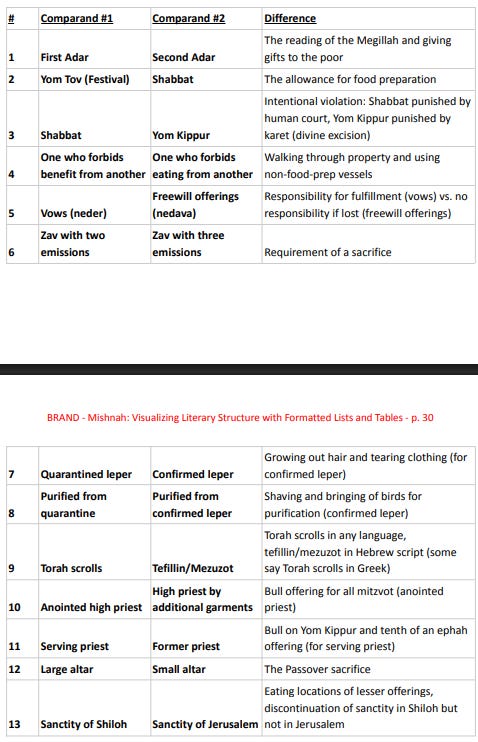

Case Study: Megillah 1:4a-11 – "A List of 13 Comparative Differences in Jewish Law: Festivals, Vows, Purity, and Sacred Spaces"

This extended list from Tractate Megillah demonstrates the power of this comparative structure.

My table (from Mishnah: Visualizing Literary Structure, p. 29-32) lays out these distinctions:

Original Hebrew:

My translation:

Difference between the first Adar and the second Adar:

the reading of the Megillah4

and the giving of gifts to the poor (מתנות לאביונים).

Difference between Yom Tov (Festival) and Shabbat:

[the permissibility of preparing on that day] necessary food (אכל נפש - okhel nefesh).

[...and so on for all 13 items, following my translation on p.31-32 of the PDF...]

The clarity afforded by this side-by-side comparison is immense.

The reader can immediately identify the precise point of legal divergence in each case.

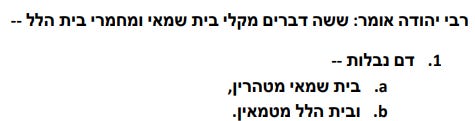

Case Study: Eduyot 5:1-4 – "17 Issues Where Beit Shammai is Lenient and Beit Hillel is Strict"

Another powerful use of contrastive lists is in presenting the differing opinions of Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel.

Tractate Eduyot is rich with such examples.

Here, I'll use the format from my first PDF (p. 41-45), where 17 such cases are detailed (though for brevity here, I'll only show the table structure and a couple of translated examples).

Table:

Original Hebrew:

My translation (Example: R' Yehuda on Blood of Carcasses):

R' Yehuda says:

There are 6 matters where Beit Shammai are lenient and Beit Hillel are stringent:

Blood of carcasses:

Beit Shammai declare it pure,

and Beit Hillel declare it impure.

This systematic presentation of rulings attributed to different Tannaim, clearly delineating their respective positions on a series of legal questions, is a hallmark of Mishnaic organization.

My tabular format simply makes these established patterns more visually accessible.

Lists of Actions, Times, and Conditions

The Mishnah also uses lists to organize complex sets of rules based on specific occasions, times, or qualifying conditions.

These lists help to present practices in a highly systematic way.

Case Study: Megillah 1:1-2 – "Megillah Reading: Possible Dates by City Type and Each of the 7 Days of the Week"

The rules for when the Megillah (Scroll [of Esther]) is read are dependent on the type of city and the day of the week on which the 14th of Adar falls.

My table (from Mishnah: Visualizing Literary Structure, p. 27-28) systematizes these variables:

Original Hebrew:

My translation (excerpt):

The Megillah (Scroll of Esther) is read

on the 11th,

12th,

13th,

14th,

[or] 15th [of Adar] —

no earlier and no later.

Walled cities from the days of Joshua bin Nun read it on the 15th.

Villages and large towns read it on the 14th, except that the villages move up the reading to the "day of assembly" (the market day, usually Monday or Thursday).

How?

If the 14th falls on a Monday:

villages and large towns read it that day,

and walled cities read it the next day.

[...and so on, following my translation on p.28-29 of the PDF...]

This table clearly lays out the seven possible scenarios for the 14th of Adar and the corresponding reading days for each type of settlement, transforming a potentially confusing set of rules into an easily digestible chart.5

Case Study: Ta'anit 2:2b-4 – "7 Special Prayers for Times of Distress Invoking Biblical Figures for Divine Mercy"

This list from Tractate Ta'anit (from Mishnah: Visualizing Literary Structure, p. 46-48) details the specific biblical figures and events invoked in a sequence of special prayers recited during a drought.

My table structure includes R' Yehuda's alternative insertions and the concluding blessings for each prayer.

Original Hebrew (from the beginning of the Mishnah section, up to and including Prayer #2):

This structured presentation allows one to follow the liturgical progression and understand the thematic connections made by the Sages between contemporary distress and historical divine interventions.

Concluding Thoughts for Part 2

The examples in this section—from numerical ranges in Arakhin to relatively intricate comparisons in Megillah and Eduyot, and conditional rules in Megillah and Ta'anit—demonstrate the Mishnaic editor’s use of lists as tools for legal precision, categorization, and pedagogical clarity.

My approach in reformatting these texts into tables and structured outlines is designed to make these inherent literary strategies more visible and accessible.

The Mishnah is not merely a collection of laws; it is a carefully constructed literary edifice. By appreciating its structural diversity, we gain a deeper insight into the Mishnaic mind.

In Part 3, we will continue this exploration by examining lists that build even larger conceptual frameworks, focusing on architectural descriptions, procedural delineations, and broad thematic enumerations.

פתח בטועה.

This phrase is unclear.

Kulp (the default translation in Sefaria) gives the traditional explanation that it’s referring to a menstruant’s uncertain blood discharge, and the numbers are clean days afterwards.

I.e., having both fixed—a set fine—and variable aspects.

The variable fine can be significantly higher than the set fine, hence it’s “stringent, strict” (להחמיר).

Literally: “There is nothing between (אין בין) X and Y except Z."

קריאת המגלה - i.e. Book of Esther.

This is a good moment to make a broader point about the Mishnah’s lists: the items they contain (which I formulize as variables X, Y, and Z in introductory schemas) are often established technical terms. From a digital humanities standpoint, these are well-suited to named entity recognition.

Notice also how using modern Arabic numerals (11th, 12th, etc. vs. spelled-out numbers: Eleventh, Twelfth, etc.) and days of week (Sunday, Monday, etc) makes the translation much more readable.