Pt2 The Biblical Books Nearly Suppressed: Reconciling Contradictions in Ecclesiastes and Proverbs (Shabbat 30b)

This is the second and final part of a two-part series. Part 1 is here, the outline for the series can be found there.

Resolving Contradictory Statements in Ecclesiastes Regarding Laughter and Joy: This World vs. the World-to-Come (Ecclesiastes 7:3, 2:2, 8:15)

The Talmud addresses apparent contradictions in Ecclesiastes regarding laughter and mirth:

On one hand, it states that "vexation/sorrow (כעס) is better than laughter (שחוק)" (Ecclesiastes 7:3), suggesting laughter is undesirable, but elsewhere, laughter is praised as commendable (מהולל) (Ecclesiastes 2:2).

Similarly, joy (שמחה) is both commended (שבחתי - Ecclesiastes 8:15) and questioned for its value (מה זה עושה - literally: “what does it do?!” - Ecclesiastes 2:2).

The Talmud resolves these contradictions by interpreting them contextually:

"Vexation is better than laughter" refers to God's punishment of the righteous in “this world” (עולם הזה; as opposed to the World-to-Come), which is ultimately preferable to the (superficial) “laughter” He grants to the wicked (through worldly blessings).

"I said of laughter: It is praiseworthy" refers to the joy and laughter that God will share with the righteous in the World-to-Come.

ומאי ״דבריו סותרין זה את זה״?

כתיב: ״טוב כעס משחוק״,

וכתיב ״לשחוק אמרתי מהולל״!

כתיב ״ושבחתי אני את השמחה״,

וכתיב ״ולשמחה מה זה עושה"!

לא קשיא

״טוב כעס משחוק״:

טוב כעס שכועס הקדוש ברוך הוא על הצדיקים בעולם הזה,

משחוק שמשחק הקדוש ברוך הוא על הרשעים בעולם הזה.

ו״לשחוק אמרתי מהולל״

זה שחוק שמשחק הקדוש ברוך הוא עם הצדיקים בעולם הבא.

And to the essence of the matter, the Gemara asks: What is the meaning of: Its statements that contradict each other?

It is written: “Vexation is better than laughter” (Ecclesiastes 7:3),

and it is written: “I said of laughter: It is praiseworthy” (Ecclesiastes 2:2), which is understood to mean that laughter is commendable.

Likewise in one verse it is written: “So I commended mirth” (Ecclesiastes 8:15),

and in another verse it is written: “And of mirth: What does it accomplish?” (Ecclesiastes 2:2).

The Gemara answers: This is not difficult, as the contradiction can be resolved.

Vexation is better than laughter means:

The vexation of the Holy One, Blessed be He, toward the righteous in this world

is preferable to the laughter which the Holy One, Blessed be He, laughs with the wicked in this world by showering them with goodness.

I said of laughter: It is praiseworthy,

that is the laughter which the Holy One, Blessed be He, laughs with the righteous in the World-to-Come.

Joy as a Prerequisite for Divine Inspiration (II Kings 3:15), Halachic Discussion, and Good Dreams

The Talmud highlights the importance of joy (שמחה), particularly the joy associated with performing mitzvot (commandments), as a necessary atmosphere for spiritual experiences and divine inspiration.

It distinguishes between the commendable "joy of a mitzva" and other forms of joy that lack spiritual purpose.

The Shekhina does not rest (שורה) on one when one is feeling sadness (עצבות), laziness (עצלות), laughter (שחוק), frivolity,1 (idle) conversation (שיחה), or idle chatter,2 but rather from joy of mitzva.3

This is exemplified by Elisha, whose prophetic spirit returned only after music lifted his mood (II Kings 3:15).4

Rav Yehuda and Rava further emphasize the value of joy: Rav Yehuda suggests cultivating joy before discussing halakha (Jewish law), and Rava recommends it before sleep to encourage positive dreams.

״ושבחתי אני את השמחה״ — שמחה של מצוה.

״ולשמחה מה זה עושה״ — זו שמחה שאינה של מצוה.

ללמדך שאין שכינה שורה

לא מתוך עצבות

ולא מתוך עצלות

ולא מתוך שחוק

ולא מתוך קלות ראש

ולא מתוך שיחה

ולא מתוך דברים בטלים,

אלא מתוך דבר שמחה של מצוה,

שנאמר:

״ועתה קחו לי מנגן

והיה כנגן המנגן,

ותהי עליו יד ה׳״.

אמר רב יהודה: וכן לדבר הלכה.

אמר רבא: וכן לחלום טוב.

[...]

Similarly, “So I commended mirth,” that is the joy of a mitzva.

“And of mirth: What does it accomplish?” that is joy that is not the joy of a mitzva.

The praise of joy mentioned here is to teach you that the Divine Presence rests upon an individual

neither from an atmosphere of sadness,

nor from an atmosphere of laziness,

nor from an atmosphere of laughter,

nor from an atmosphere of frivolity,

nor from an atmosphere of idle conversation,

nor from an atmosphere of idle chatter,

but rather from an atmosphere imbued with the joy of a mitzva.

As it was stated with regard to Elisha that after he became angry at the king of Israel, his prophetic spirit left him until he requested:

“But now bring me a minstrel;

and it came to pass, when the minstrel played,

that the hand of the Lord came upon him” (II Kings 3:15).

Rav Yehuda said: And, so too, one should be joyful before stating a matter of halakha.

Rava said: And, so too, one should be joyful before going to sleep in order to have a good dream.

[...]

Contradictory Wisdom: The Consideration of Suppressing the Book of Proverbs

The Talmud discusses the Sages' consideration of suppressing the book of Proverbs (משלי) due to its seemingly contradictory statements but ultimately decided against it, as they had successfully reconciled contradictions in Ecclesiastes (as discussed in previous sections in this sugya).

ואף ספר משלי בקשו לגנוז,

שהיו דבריו סותרין זה את זה.

ומפני מה לא גנזוהו?

אמרי:

ספר קהלת, לאו עיינינן, ואשכחינן טעמא?!

הכא נמי, ליעיין.

And, the Gemara continues, the Sages sought to suppress the book of Proverbs as well

because its statements contradict each other.

And why did they not suppress it?

They said: In the case of the book of Ecclesiastes, didn’t we analyze it and find an explanation that its statements were not contradictory?

Here too, let us analyze it.

Wisdom in Context: Reconciliation of Contradictory Proverbs on Engaging with Fools (Proverbs 26:4-5)

The Talmud explains the apparent contradiction within Proverbs 26:4-5: the verse first advises not to answer a fool,5 and then immediately after advises answering a fool (to prevent him from becoming self-conceited).

The resolution is that the advice depends on the context: one should answer a fool regarding Torah matters but refrain from engaging with a fool on secular topics (מילי דעלמא).

ומאי דבריו סותרים זה את זה?

כתיב ״אל תען כסיל כאולתו״,

וכתיב: ״ענה כסיל כאולתו״.

לא קשיא:

הא בדברי תורה,

הא במילי דעלמא.

And what is the meaning of: Its statements contradict each other?

On the one hand, it is written: “Answer not a fool according to his folly, lest you also be like him” (Proverbs 26:4),

and on the other hand, it is written: “Answer a fool according to his folly, lest he be wise in his own eyes” (Proverbs 26:5).

The Gemara resolves this apparent contradiction: This is not difficult,

as this, where one should answer a fool, is referring to a case where the fool is making claims about Torah matters;

whereas that, where one should not answer him, is referring to a case where the fool is making claims about mundane matters.

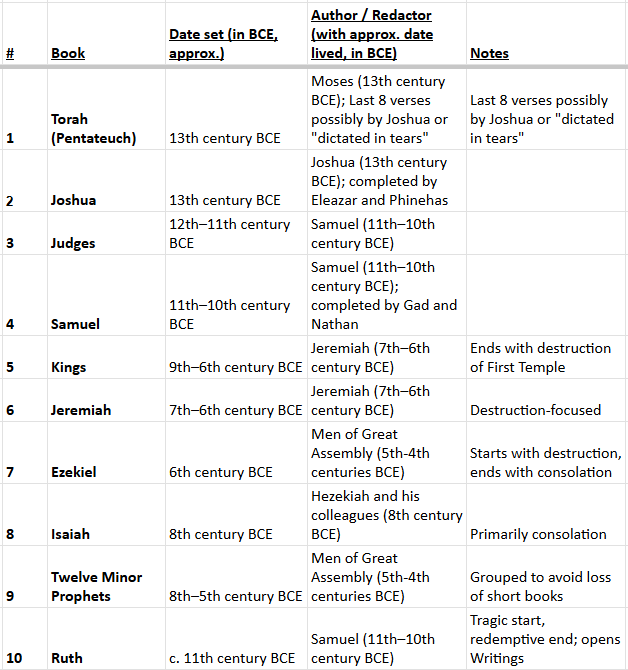

Appendix - The Order and Authorship of Biblical Books (Bava Batra 14b-15a)

Order of Neviim (“Prophets”): Joshua, Judges, Samuel, Kings, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Isaiah, and the Twelve [Minor Prophets]

A baraita lists the canonical order of the ‘Nevi'im’ (נביאים - ”Prophets”): Joshua, Judges, Samuel, Kings, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Isaiah,6 and “the Twelve”.7

תנו רבנן,

סדרן של נביאים:

יהושע

ושופטים,

שמואל

ומלכים,

ירמיה

ויחזקאל,

ישעיה

ושנים עשר.

§ A baraita states:

The order of the books of the Prophets when they are attached together is as follows:

Joshua

and Judges,

Samuel

and Kings,

Jeremiah

and Ezekiel,

and Isaiah

and the Twelve Prophets.

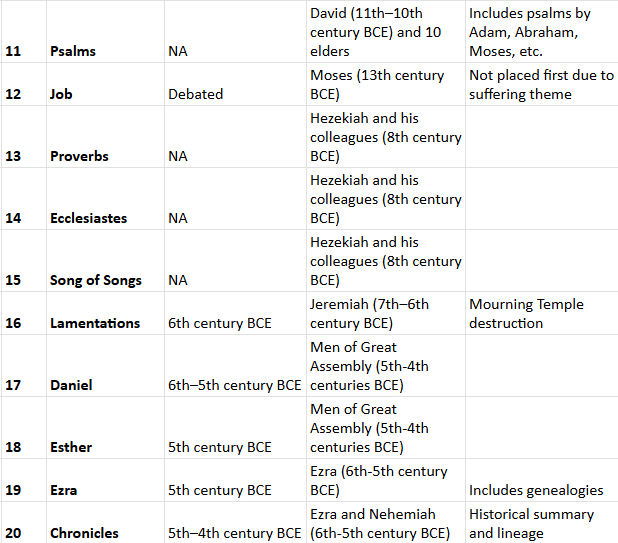

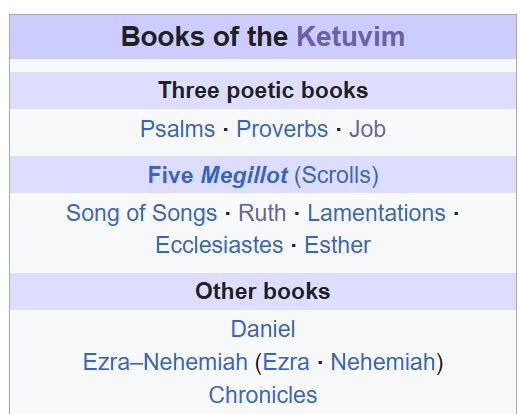

Order of Ketuvim (“Writings”): Ruth, Psalms, Job, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs, Lamentations, Daniel, Esther, Ezra, and Chronicles

The baraita then presents the order of Ketuvim (כתובים - “Writings”): Ruth, Psalms, Job,8 Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs, Lamentations,9 Daniel, Esther (מגילת אסתר), Ezra, and Chronicles.10

סידרן של כתובים:

רות

וספר תהלים

ואיוב

ומשלי,

קהלת,

שיר השירים

וקינות,

דניאל

ומגילת אסתר,

עזרא

ודברי הימים.

The baraita continues: The order of the Writings is:

Ruth

and the book of Psalms,

and Job

and Proverbs;

Ecclesiastes,

Song of Songs,

and Lamentations;

Daniel

and the Scroll of Esther;

and Ezra

and Chronicles.

Attribution of Authorship of Biblical Books

The baraita lists the (traditionally-understood) authors of biblical books.

ומי כתבן?

The baraita now considers the authors of the biblical books:

And who wrote the books of the Bible?

Moses, Joshua, Samuel, and David

Moses: Torah,11 “the portion of Balaam” (פרשת בלעם), and Job

Joshua: Book of Joshua,12 and [the final] 8 verses of the Torah13

Samuel: Book of Samuel,14 Judges, and Ruth

David: Psalms, with contributions from 10 elders (as listed in the next section)

משה כתב --

ספרו

ופרשת בלעם

ואיוב.

יהושע כתב --

ספרו

ושמונה פסוקים שבתורה.

שמואל כתב --

ספרו

ושופטים

ורות.

דוד כתב --

ספר תהלים –

Moses wrote --

his own book, i.e., the Torah,

and the portion of Balaam in the Torah,

and the book of Job.

Joshua wrote --

his own book

and 8 verses in the Torah, which describe the death of Moses.

Samuel wrote --

his own book,

the book of Judges,

and the book of Ruth.

David wrote --

the book of Psalms

David wrote Psalms with contributions from 10 Elders - Adam, Melchizedek, Abraham, Moses, Heman, Jeduthun, Asaph, and the 3 sons of Korah

David wrote Psalms with contributions from 10 Elders (זקנים):

Adam, Melchizedek, Abraham, Moses, Heman,15 Jeduthun, Asaph, and the 3 sons of Korah.16

על ידי עשרה זקנים:

על ידי אדם הראשון,

על ידי מלכי צדק,

ועל ידי אברהם,

ועל ידי משה,

ועל ידי הימן,

ועל ידי ידותון,

ועל ידי אסף,

ועל ידי שלשה בני קרח.

by means of 10 elders of previous generations, assembling a collection that included compositions of others along with his own. He included psalms authored

By Adam the first man,

by Melchizedek king of Salem,

and by Abraham,

and by Moses,

and by Heman,

and by Jeduthun,

and by Asaph,

and by the three sons of Korah.

Compilation by Later Redactors: Jeremiah, Hezekiah, Men of the Great Assembly, Ezra, and Nehemiah

Other books were compiled or finalized by:

Jeremiah: Book of Jeremiah, Kings, and Lamentations

Hezekiah (c. 700 BCE) and his colleagues (סיעתו): Isaiah, Proverbs, Song of Songs, and Ecclesiastes

The Men of the Great Assembly (c. 5th-4th centuries BCE): Ezekiel, the Twelve [Minor Prophets], Daniel, and Esther

Ezra: Book of Ezra, and the genealogical material (יחס) in Chronicles up to his time

ירמיה כתב --

ספרו

וספר מלכים

וקינות.

חזקיה וסיעתו כתבו --

ישעיה,

משלי,

שיר השירים

וקהלת.

אנשי כנסת הגדולה כתבו --

יחזקאל

ושנים עשר,

דניאל

ומגילת אסתר.

עזרא כתב --

ספרו,

ויחס של דברי הימים עד לו.

Jeremiah wrote --

his own book,

and the book of Kings,

and Lamentations.

Hezekiah and his colleagues wrote --

Isaiah [Yeshaya],

Proverbs [Mishlei],

Song of Songs [Shir HaShirim],

and Ecclesiastes [Kohelet].

The members of the Great Assembly wrote --

Ezekiel [Yeḥezkel ],

and the Twelve Prophets [Sheneim Asar],

Daniel [Daniel ],

and the Scroll of Esther [Megillat Ester].

Ezra wrote --

his own book

and the genealogy of the book of Chronicles until his period.

קלות ראש - literally: “lightness of head”, an idiom referring to a state of lacking seriousness.

Another instance where laughter and frivolity are portrayed negatively can be found in Avot.3.13:

רבי עקיבא אומר:

שחוק וקלות ראש —

מרגילין לערוה.

R’ Akiva said:

Merriment (שחוק) and frivolity (קלות ראש) —

accustom one to sexual licentiousness (ערוה - forbidden sex)

דברים בטלים - literally: “worthless/frivolous things”. The same term is used in the poem said upon leaving the study hall, contrasting these “frivolous things” with “Torah matters”, quoted in a footnote in Part 1 of this series:

שאני משכים, והם משכימים:

אני משכים לדברי תורה,

והם משכימים לדברים בטלים.

I rise early (משכים), and they rise early:

I rise early to pursue matters of Torah,

and they rise early to pursue frivolous matters (דברים בטלים).

See also a similar contrasting later in the sugya between “secular/mundane matters” and “Torah matters”.

And the same phrase is used in my piece here, section “R’ Eliezer’s Trial Before the Romans for Heresy and Acquittal“:

אמר לו אותו הגמון:

זקן שכמותך יעסוק בדברים בטלים הללו?!

The hegemon said to him:

Why should an elder like you engage in these frivolous matters (דברים בטלים) of heresy?!

However, the word batel (בָּטַל) doesn’t always have negative connotations; it’s also the word used positively to describe a Torah scholar who doesn’t or shouldn’t work. For example Mishnah_Pesachim.4.5 (with adjustments to the translation as needed):

מקום שנהגו לעשות מלאכה בתשעה באב — עושין.

מקום שנהגו שלא לעשות מלאכה — אין עושין.

ובכל מקום תלמידי חכמים בטלים.

רבן שמעון בן גמליאל אומר: לעולם יעשה אדם עצמו תלמיד חכם.

In a place where people were accustomed to work (לעשות מלאכה - literally: “do labor”) on [the fast of] Tisha B'Av (תשעה באב), one does [work].

In a place where people were accustomed not to work (due to the mourning over the Temple’s destruction), one does not do [work].

And in all places Torah scholars (תלמידי חכמים) are idle (בטלים) and do not work on Tisha B'Av.

Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel says: With regard to Tisha B'Av, a person should always make himself [like] a Torah scholar and refrain from performing labor.

See also the terrm batlan (בַּטְלָן), “idler, slacker”, in the phrase talmudic term “ten idlers” (עשרה בטלנים), see here (my translation):

The term "Ten Idlers" […] refers to a group of ten individuals who abstain from any form of work and dedicate themselves solely to sitting in the synagogue all day or during prayer times.

This group is included in the 120 individuals required for a city to host a Sanhedrin, and without them, the city is not considered a proper city regarding the reading of the Megillah.

Almost exactly the same lists, in the same formula, appear in a baraita cited in Berakhot.31a.11-12, which discusses appropriate emotional state for prayer and for bidding farewell (יפטר) to a friend:

תנו רבנן:

אין עומדין להתפלל

לא מתוך עצבות,

ולא מתוך עצלות,

ולא מתוך שחוק,

ולא מתוך שיחה,

ולא מתוך קלות ראש,

ולא מתוך דברים בטלים,

אלא מתוך שמחה של מצוה.

וכן לא יפטר אדם מחברו

לא מתוך שיחה,

ולא מתוך שחוק,

ולא מתוך קלות ראש,

ולא מתוך דברים בטלים,

אלא מתוך דבר הלכה.

On the topic of proper preparation for prayer, the Sages taught:

One may not stand to pray

Not from an atmosphere of sorrow

nor from an atmosphere of laziness,

nor from an atmosphere of laughter,

nor from an atmosphere of conversation,

nor from an atmosphere of frivolity,

nor from an atmosphere of purposeless matters.

Rather, one should approach prayer from an atmosphere imbued with the joy of a mitzva.

Similarly, a person should not take leave of another

Not from an atmosphere of conversation,

nor from an atmosphere of laughter,

nor from an atmosphere of frivolity,

nor from an atmosphere of purposeless matters.

Rather, one should take leave of another from involvement in a matter of halakha.

The first list has the exact same six items, and concludes the same way: “Rather, one should approach prayer from an atmosphere imbued with the joy of a mitzva“ (שמחה של מצוה).

The second list has four out of the six items, and concludes differently: “Rather, one should take leave of another from involvement in a matter of halakha“ (דבר הלכה).

This tamudic passage is alluded to by Maimonides in his Mishneh Torah when he discusses prophecy, see ibid., Laws of the Foundations of the Torah, 7:4 (with adjustments to the translation, as needed):

כל הנביאים אין מתנבאין בכל עת שירצו

אלא מכונים דעתם, ויושבים שמחים וטובי לב, ומתבודדים.

שאין הנבואה שורה לא מתוך עצבות, ולא מתוך עצלות, אלא מתוך שמחה.

לפיכך בני הנביאים לפניהם נבל, ותף, וחליל, וכנור, והם מבקשים הנבואה.

All the prophets do not prophesy whenever they desire.

Instead, they must direct (מכונים) their mind (דעתם) and seclude themselves (מתבודדים), in a happy (שמחים) and joyous mood (טובי לב).

Because prophecy cannot rest [upon a person] in [a state of] sadness (עצבות) or laziness (עצלות), [but] only in [a state of] happiness (שמחה).

Therefore, the prophets' disciples (בני הנביאים) would always have a harp, drum, flute, and lyre [when] they were seeking prophecy.

Note Maimonides' substitution of "prophecy" for "Shekhina" in the statement asserting that prophecy can only rest upon a joyful individual. This is likely due to Maimonides' more naturalistic interpretation of the mechanism of prophecy. See his famous line (I elide the long passage on the qualities needed for prophecy), at the beginning of that chapter, ibid. 7:1:

אדם שהוא ממלא בכל המדות האלו

[…]

מיד רוח הקדש שורה עליו

A person who is full of all these qualities (מדות)

[…]

the divine spirit (רוח הקדש) will immediately rest upon him.

And see his passage, quoted in my piece here, section “Appendix #1 - The Angelic Hierarchy (MT, Laws of Foundations of the Torah, 2:7)“, where he explicitly states that prophetic visions are communicated to the prophet via the lowest category of angels:

ומעלה עשירית היא מעלת הצורה שנקראת אישים

והם המלאכים המדברים עם הנביאים, ונראים להם במראה הנבואה.

לפיכך נקראו "אישים", שמעלתם קרובה למעלת דעת בני אדם

The tenth [=lowest] level (מעלה) [of angels] is that of the form (צורה) called Ishim (אישים)

They are the angels who communicate with the prophets and are perceived by them in prophetic visions.

Therefore, they are called Ishim (“men”), because their level is close to the level of human knowledge.

כסיל - as the verse explains: to avoid becoming like him.

See the Talmud on the order of the books of Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Isaiah, explaining why Isaiah is reordered after Jeremiah and Ezekiel, though he chronologically precedes them.

The Talmud explains that the editorial logic is thematic: Kings ends with destruction; Jeremiah describes destruction; Ezekiel transitions from destruction to consolation; Isaiah is mostly consolation. The sequence thus moves from catastrophe to hope.

The full passage, Bava_Batra.14b.10:

מכדי ישעיה קדים מירמיה ויחזקאל,

ליקדמיה לישעיה ברישא!

כיון דמלכים סופיה חורבנא;

וירמיה כוליה חורבנא;

ויחזקאל רישיה חורבנא וסיפיה נחמתא;

וישעיה כוליה נחמתא –

סמכינן חורבנא לחורבנא,

ונחמתא לנחמתא.

The Talmud further asks: Consider: Isaiah preceded Jeremiah and Ezekiel;

let the book of Isaiah precede the books of those other prophets.

The Talmud answers: Since the book of Kings ends with the destruction of the Temple,

and the book of Jeremiah deals entirely with prophecies of the destruction,

and the book of Ezekiel begins with the destruction of the Temple but ends with consolation and the rebuilding of the Temple,

and Isaiah deals entirely with consolation, as most of his prophecies refer to the redemption,

we juxtapose destruction to destruction and consolation to consolation.

This accounts for the order: Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Isaiah.

שנים עשר - i.e. the Twelve Minor Prophets.

In general, on this list, compare the Wikipedia template box “Books of Nevi'im”:

See the Talmud on the order of the books of Job and Ruth:

If Job lived in Moses’ time (as one opinion holds), it should come first.

The Talmud responds that one does not begin a section of Scripture with a book of suffering.

Ruth, though it begins in tragedy, ends in redemption—hence it opens the Writings.

The full passage, in Bava_Batra.14b.11:

ולמאן דאמר: איוב בימי משה היה, ליקדמיה לאיוב ברישא!

אתחולי בפורענותא לא מתחלינן.

רות נמי פורענות היא!

פורענות דאית ליה אחרית –

דאמר רבי יוחנן:

למה נקרא שמה רות?

שיצא ממנה דוד,

שריוהו להקדוש ברוך הוא בשירות ותושבחות.

The Talmud asks: And according to the one who says that Job lived in the time of Moses, let the book of Job precede the others.

The Talmud answers: We do not begin with suffering, i.e., it is inappropriate to start the Writings with a book that deals so extensively with suffering.

The Talmud asks: But the book of Ruth, with which the Writings opens, is also about suffering, since it describes the tragedies that befell the family of Elimelech.

The Talmud answers: This is suffering which has a future of hope and redemption.

As R' Yoḥanan says: Why was she named Ruth, spelled reish, vav, tav?

Because there descended from her David who sated, a word with the root reish, vav, heh, God, with songs and praises.

קינות - traditionally referred to as: אֵיכָה (‘Eikha’), from its incipit meaning "how".

In general, on this list, compare the Wikipedia template box “Books of Ketuvim”:

ספרו - literally: “his own book”, i.e. the Pentateuch.

On this, see the Talmud, Bava_Batra.15a.7:

יהושע כתב ספרו.

והכתיב: ״וימת יהושע בן נון עבד ה׳״!

דאסקיה אלעזר.

והכתיב: ״ואלעזר בן אהרן מת״!

דאסקיה פנחס.

It is stated in the baraita that Joshua wrote his own book.

The Talmud asks: But isn’t it written toward the end of the book: “And Joshua, son of Nun, the servant of YHWH, died” (Joshua 24:29)?

Is it possible that Joshua wrote this?

The Talmud answers: Aaron’s son Eleazar completed it.

The Talmud asks: But isn’t it also written: “And Eleazar, son of Aaron, died” (Joshua 24:33)?

The Talmud answers: Pinehas completed it.

On this, see the Talmud, Bava_Batra.15a.4-5:

אמר מר:

יהושע כתב --

ספרו ושמונה פסוקים שבתורה.

תניא כמאן דאמר:

שמונה פסוקים שבתורה יהושע כתבן.

דתניא

״וימת שם משה עבד ה׳״ –

אפשר משה מת,

וכתב: ״וימת שם משה״?!

אלא

עד כאן כתב משה,

מכאן ואילך כתב יהושע;

דברי רבי יהודה,

ואמרי לה: רבי נחמיה.

The Talmud elaborates on the particulars of this baraita:

The Master said above that

Joshua wrote his own book and 8 verses of the Torah.

The Talmud comments: This baraita is taught in accordance with the one who says that

it was Joshua who wrote the last 8 verses in the Torah.

This point is subject to a tannaitic dispute, as it is taught in another baraita:

“And Moses the servant of YHWH died there” (Deuteronomy 34:5);

is it possible that after Moses died,

he himself wrote “And Moses died there”?!

Rather,

Moses wrote the entire Torah until this point,

and Joshua wrote from this point forward;

this is the statement of R' Yehuda.

And some say that R' Neḥemya stated this opinion.

אמר לו רבי שמעון:

אפשר ספר תורה חסר אות אחת,

וכתיב: ״לקח את ספר התורה הזה״?!

אלא

עד כאן --

הקדוש ברוך הוא אומר –

ומשה אומר וכותב;

מכאן ואילך --

הקדוש ברוך הוא אומר –

ומשה כותב בדמע,

כמו שנאמר להלן:

״ויאמר להם ברוך:

מפיו יקרא אלי את כל הדברים האלה,

ואני כותב על הספר בדיו״.

R' Shimon said to him:

Is it possible that the Torah scroll was missing a single letter?

But it is written: “Take this Torah scroll” (Deuteronomy 31:26), indicating that the Torah was complete as is and that nothing further would be added to it.

Rather,

until this point --

God dictated

and Moses repeated after Him and wrote the text.

From this point forward, with respect to Moses’ death --

God dictated

and Moses wrote with tears.

The fact that the Torah was written by way of dictation can be seen later, as it is stated concerning the writing of the Prophets:

“And Baruch said to them:

He dictated all these words to me,

and I wrote them with ink in the scroll” (Jeremiah 36:18).

On this, see the Talmud, Bava_Batra.15a.8:

שמואל כתב ספרו.

והכתיב: ״ושמואל מת״!

דאסקיה גד החוזה ונתן הנביא.

It is also stated in the baraita that Samuel wrote his own book.

The Talmud asks: But isn’t it written: “And Samuel died” (I Samuel 28:3)?

The Talmud answers: Gad the seer and Nathan the prophet finished it.

The Talmud asks on this, Bava_Batra.15a.10:

קא חשיב משה וקא חשיב הימן,

והאמר רב:

הימן זה משה –

כתיב הכא: ״הימן״,

וכתיב התם: ״בכל ביתי נאמן הוא״!

תרי הימן הוו.

The Talmud asks: The baraita counts Moses among the ten elders whose works are included in the book of Psalms, and it also counts Heman.

But doesn’t Rav say:

The Heman mentioned in the Bible (I Kings 5:11) is the same person as Moses?

This is proven by the fact that

it is written here: “Heman” (Psalms 88:1), which is Aramaic for trusted,

and it is written there about Moses: “For he is the trusted one in all My house” (Numbers 12:7).

The Talmud answers: There were two Hemans, one of whom was Moses, and the other a Temple singer from among the descendants of Samuel.

On this list, see the Talmud, Bava_Batra.15a.9:

דוד כתב ספר תהלים –

על ידי עשרה זקנים.

וליחשוב נמי איתן האזרחי!

אמר רב:

איתן האזרחי זה הוא אברהם –

כתיב הכא: ״איתן האזרחי״,

וכתיב התם: ״מי העיר ממזרח צדק [וגו׳]״.

It is further stated that David wrote the book of Psalms

by means of 10 elders, whom the baraita proceeds to list.

The Talmud asks: But then let it also count Ethan the Ezrahite among the contributors to the book of Psalms, as it is he who is credited with Psalms, chapter 89.

Rav says:

Ethan the Ezrahite is the same person as Abraham.

Proof for this is the fact that

it is written here: “A Maskil of Ethan the Ezrahite” (Psalms 89:1),

and it is written there: “Who raised up one from the east [mizraḥ], whom righteousness met wherever he set his foot” (Isaiah 41:2).

The latter verse is understood as referring to Abraham, who came from the east, and for that reason he is called Ethan the Ezrahite in the former verse.