Rome and the Final Judgment: The Messianic-Era Judgement Day in the Talmud and Rome's Role (Avodah Zarah 2a-b)

On the End of Days in Talmudic thought, see the Hebrew Wikipedia entry on “Judgment Day” > section “Judgement Day in Judaism” (translation mine, with adjustments):

In Judaism, the Day of Judgment marks the day when all the creators of the world stand before God, and give judgment for their actions. In the Bible, the future Day of Judgment appears in the names "Day of the Lord" (yom YHWH), or the day "of judgment" (mishpat).

Judgment Day is also a name in Judaism for Rosh Hashanah, which is the day of general judgment for all the creatures of the world, where everything is put on trial and their sentence is written - whether to death or to life.

And see Hebrew Wikipedia, entry “Ancient Rome” > section “Rome in the literature of the Sages” (translation mine, with adjustments):

Most of the Talmudic sages were active and wrote during the time of the Roman rule in the Land of Israel. The image of the Roman rule in the Land of Israel that emerges from the Talmud is extremely negative, due to the cultural and religious challenge that the government posed to the people of Israel, and due to the suppression of the people's rebellions and struggles against the government. An example of the attitude of the Jewish leadership to the Roman government, and their attitude to the Jewish leadership can be found in the Babylonian Talmud, where it is said that Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai criticized the Romans harshly:

‘Everything they repaired they did not repair except for their own needs - they repaired markets to seat prostitutes in, baths to purify themselves in, bridges to collect tolls from.’

According to the story, Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai was sentenced to death following his words, and was forced to go underground.

Another example can be found in the Talmud's interpretation of the vision of the Four Kingdoms that appears in the book of Daniel - according to the Talmud's interpretation, Rome is the fourth kingdom, the most terrible of them all.

The founding of Rome is described in the Jerusalem Talmud, as a gradual founding, where every step was caused by a spiritual decline in the people of Israel:

‘R’ Levi said, on the day that Solomon married [the daughter of] Pharaoh Necho, king of Egypt, Michael went down and stuck a reed in the sea and created a shoal, and a large forest was formed, and this is the great city of Rome. The day that Jeroboam set up two golden calves, Remus and Romulus came and built two huts in Rome.1 The day that Elijah departed, a king was appointed in Rome.’

The Passage

Analyzed in Rubenstein, Talmudic Stories, Chapter 7 (p. 275ff).2

Gathering the Nations for Judgement

דרש רבי חנינא בר פפא,

ואיתימא רבי שמלאי:

לעתיד לבא מביא הקדוש ברוך הוא ספר תורה [ומניחו] בחיקו,

ואומר למי שעסק בה – "יבא ויטול שכרו";

§ The Talmud cites homiletic interpretations of the verse that was discussed earlier: “All the nations are gathered together, and let the peoples be assembled; who among them can declare this, and announce to us former matters? Let them bring their witnesses, that they may be justified; and let them hear, and say: It is truth” (Isaiah 43:9).

R’ Ḥanina bar Pappa taught,

and some say that it was R’ Simlai who taught:

In the future, God will bring a Torah scroll and place it in His lap

and say: Anyone who engaged in its study should come and take his reward.

(Genesis 25:23)

מיד מתקבצין ובאין עובדי כוכבים בערבוביא

שנאמר (ישעיהו מג, ט) כל הגוים נקבצו יחדו [וגו']

אמר להם הקדוש ברוך הוא:

אל תכנסו לפני בערבוביא,

אלא תכנס כל אומה ואומה וסופריה,

שנאמר 'ויאספו לאומים',

ואין לאום אלא מלכות,

שנאמר (בראשית כה, כג) ולאום מלאום יאמץ

[…]

Immediately, the nations of the world will gather together and come intermingled with each other,

as it is stated: “All the nations are gathered together and let the peoples be assembled.”

God will say to them:

Do not enter before Me intermingled;

rather, let each and every nation enter with their scholars,

as it is stated: “And let the peoples [le’umim] be assembled” (Isaiah 43:9);

and the term le’om means nothing other than kingdom,

as it is stated: “And the one kingdom [u-le’om] shall be stronger than the other kingdom [mi-le’om]” (Genesis 25:23).

[…]

Rome (Daniel 7:23)

[מיד] נכנסה לפניו מלכות רומי תחלה;

מאי טעמא?

משום דחשיבא.

ומנלן דחשיבא?

דכתי' (דניאל ז, כג) ותאכל כל ארעא ותדושינה ותדוקינה

אמר רבי יוחנן:

זו רומי חייבת

שטבעה יצא בכל העולם.

Immediately, the Roman Empire enters first before Him.

The Talmud asks: What is the reason that the Roman Empire enters first?

It is because the Roman Empire is the most important of all of the nations.

And from where do we derive that it is the most important?

As it is written in the book of Daniel with regard to the fourth empire that will rule over the world: “And it shall devour the whole earth, and shall tread it down, and break it in pieces” (Daniel 7:23),

and R’ Yoḥanan says:

This empire that will devour the earth is the wicked Roman Empire,

whose name spread throughout the world.

(I Kings 8:59)

ומנא לן דמאן דחשיב עייל ברישא?

כדרב חסדא,

דאמר רב חסדא:

מלך וצבור —

מלך נכנס תחלה לדין,

שנאמר (מלכים א ח, נט):

לעשות משפט עבדו

ומשפט עמו ישראל [וגו']

The Talmud asks: And from where do we derive that whoever is more important enters first?

This is in accordance with a statement of Rav Ḥisda,

as Rav Ḥisda says:

When a king and a community are brought before God for judgment —

the king enters for judgment first,

as it is stated:

“That He make the judgment of His servant

and the judgment of His people Israel, as every day shall require” (I Kings 8:59).

וטעמא מאי?

איבעית אימא: לאו אורח ארעא למיתב מלכא מאבראי,

ואיבעית אימא: מקמי דליפוש חרון אף

And what is the reason that it is important for the king to enter first?

If you wish, say that it is not proper conduct for the king to stand outside and wait for the trial of his subjects to end.

And if you wish, say instead that the king is brought in first so that he may be judged before God’s anger intensifies due to the sins of the community.

אמר להם הקב"ה: במאי עסקתם?

אומרים לפניו:

ריבונו של עולם!

הרבה שווקים תקנינו,

הרבה מרחצאות עשינו,

הרבה כסף וזהב הרבינו,

וכולם לא עשינו אלא בשביל ישראל כדי שיתעסקו בתורה.

The Talmud returns to its narration of the future judgment. First, the members of the Roman Empire enter.

God says to them: With what did you occupy yourselves?

They say before Him in response:

God!

we have established many marketplaces,

we have built many bathhouses,

and we have increased much silver and gold.

And we did all of this only for the sake of the Jewish people, so that they would be free to engage in Torah study.

(Haggai 2:8)

אמר להם הקב"ה:

שוטים שבעולם!

כל מה שעשיתם לצורך עצמכם עשיתם:

תקנתם שווקים

להושיב בהן זונות,

מרחצאות

לעדן בהן עצמכם;

כסף וזהב -

שלי הוא,

שנאמר (חגי ב, ח) לי הכסף ולי הזהב נאם ה' צבאות;

God says to them:

Fools of the world!

Are you attempting to deceive Me?! Everything that you did, you did for your own needs.

You established marketplaces

to place prostitutes in them;

you built bathhouses

for your own enjoyment;

and as for the silver and gold that you claim to have increased,

it is Mine,

as it is stated: “Mine is the silver, and Mine the gold, said YHWH of hosts” (Haggai 2:8).

(Isaiah 43:9)

כלום יש בכם מגיד זאת?

שנאמר: ״מי בכם יגיד זאת״,

ואין ״זאת״ אלא תורה,

שנאמר: ״וזאת התורה אשר שם משה״.

מיד יצאו בפחי נפש

Is there no one among you who can declare that they have studied this Torah?

This is the meaning of the continuation of the verse from Isaiah, as it is stated: “Who among them can declare this?” (Isaiah 43:9).

And “this” is referring to nothing other than the Torah,

as it is stated: “And this is the Torah that Moses set before the children of Israel” (Deuteronomy 4:44), and whoever did not engage in its study does not receive reward.

Immediately, the members of the Roman Empire leave disappointed.

Persian Empire

יצאת מלכות רומי,

ונכנסה מלכות פרס אחריה.

[…]

The Roman Empire leaves,

and the Persian Empire enters after it.

[…]

אמר להם הקדוש ברוך הוא: במאי עסקתם?

אומרים לפניו:

רבונו של עולם!

הרבה גשרים גשרנו,

הרבה כרכים כבשנו,

הרבה מלחמות עשינו,

וכולם לא עשינו אלא בשביל ישראל כדי שיתעסקו בתורה.

God, says to them: With what did you occupy yourselves?

They say before Him in response:

God!

we have built many bridges,

we have conquered many cities,

and we have fought many wars.

And we did all of this only for the sake of the Jewish people, so that they would engage in Torah study.

אמר להם הקדוש ברוך הוא:

כל מה שעשיתם לצורך עצמכם עשיתם:

תקנתם גשרים —

ליטול מהם מכס,

כרכים —

לעשות בהם אנגריא,

מלחמות —

אני עשיתי,

שנאמר: ״ה׳ איש מלחמה״,

כלום יש בכם מגיד זאת?

שנאמר: ״מי בכם יגיד זאת״, ואין ״זאת״ אלא תורה, שנאמר: ״וזאת התורה אשר שם משה״, מיד יצאו מלפניו בפחי נפש.

God says to them:

Everything that you did, you did for your own needs:

You established bridges —

to collect taxes from all who pass over them.

You conquered cities —

to use their residents for forced labor [angareya];

and with regard to fighting the wars —

I wage wars, and your success is from Me, as it is stated: “YHWH is a man of war” (Exodus 15:3).

Is there no one among you who can declare that they have studied this Torah?

As it is stated: “Who among them can declare this” (Isaiah 43:9),

and “this” is referring to nothing other than the Torah,

as it is stated: “And this is the Torah that Moses set” (Deuteronomy 4:44).

Immediately, the members of the Persian Empire leave from before Him disappointed.

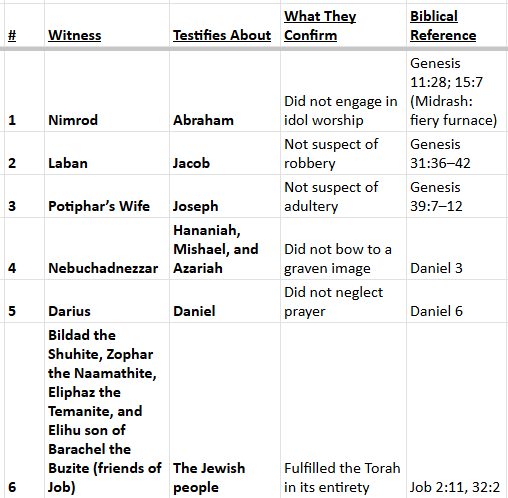

Appendix - Non-Jewish Biblical Adversaries Who In the Future Messianic Judgement Day Will Affirm the Righteousness of Israel’s Patriarchs, Prophets, and the People in Their Fulfillment of the Torah (Avodah Zarah 3a)

אמר להם הקדוש ברוך הוא:

מכם יבאו ויעידו בהן בישראל שקיימו את התורה כולה:

God says to the non-Jewish nations:

Let the witnesses come from among you and testify that the Jewish people fulfilled the Torah in its entirety:

יבא נמרוד

ויעיד באברהם

שלא עבד עבודה זרה,

יבא לבן

ויעיד ביעקב

שלא נחשד על הגזל,

תבא אשת פוטיפרע

ותעיד ביוסף

שלא נחשד על העבירה.

יבא נבוכדנצר

ויעיד בחנניה מישאל ועזריה

שלא השתחוו לצלם,

יבא דריוש

ויעיד בדניאל

שלא ביטל את התפלה,

יבא

בלדד השוחי

וצופר הנעמתי

ואליפז התימני

ואליהו בן ברכאל הבוזי

ויעידו בהם בישראל

שקיימו את כל התורה כולה,

שנאמר: ״יתנו עדיהם ויצדקו״.

Let Nimrod come

and testify about Abraham

that he did not engage in idol worship.

Let Laban come

and testify about Jacob

that he is not suspect with regard to robbery (see Genesis 31:36–42).

Let the wife of Potiphar come

and testify about Joseph

that he is not suspect with regard to the sin of adultery (see Genesis 39:7–12).

Let Nebuchadnezzar come

and testify about Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah

that they did not prostrate themselves before a graven image.

Let Darius come

and testify about Daniel

that he did not neglect his prayer (see Daniel 6).

Let

Bildad the Shuhite,

and Zophar the Naamathite,

and Eliphaz the Temanite,

and Elihu, son of Barachel, the Buzite, friends of Job (see Job 2:11 and 32:2)

come and testify about the Jewish people

that they fulfilled the Torah in its entirety.

As it is stated: “All the nations are gathered together…let them bring their witnesses, that they may be justified” (Isaiah 43:9),

i.e., the gathered non-Jews will submit testimony on behalf of the Jewish people and demonstrate the Jews’ righteousness.

The reference to the Hut of Romulus is fascinating. Casa Romuli - Wikipedia: “The Casa Romuli ("Hut of Romulus") […] was the reputed dwelling place of the legendary founder and first king of Rome, Romulus (traditional dates 771–717 BC). It was situated [in Rome].”

Rubenstein’s analyses are quite good. My only real issue is that he overdoes finding patterns of “keywords”. This is an example of “patternicity” - finding patterns where none were intended. See a similar critique by James Kugel, in his online appendix to How to Read the Bible (2007), on literary readings of the Bible, pioneered by Robert Alter’s The Art of Biblical Narrative (1981). The same critique can even more so be made by contemporary Gush-style readings of Tanach, where analysis based on patterns of keywords is taken to extremes.

He also overdoes finding overall structure, such as “chiastic” structure. A similar critique can be had on Bible scholars.

Kugel, ‘Appendix 1: Apologetics and “Biblical Criticism Lite” ‘ (with hyperlinks to Wikipedia added, where relevant):

“[W]hat seems to me problematic about the literary approach is that it regularly ends up implying that that final form of the Bible is something that, in fact, it never was, literature in the same sense that the writings of Boccaccio or Goethe or Pushkin or Balzac are literature […] [E]ven if I could wave my wand and forget about J, E, P, H and D, dismissing them as if they were a single author’s preliminary drafts and focusing only on the book of Genesis as it now is, nevertheless, that would not turn it in to literature unless I were prepared to assume something about its genre that is largely inappropriate. Neither the original authors nor the final editors and canonizers of Genesis were out to create literature of the Boccaccio kind; even to compare the stories of Genesis to their rewriting in Paradise Lost would be a bit off. In the beginning, most of Genesis was to be understood as a series of etiological explanations of the present, while for its canonizers Genesis was part of a great divine guidebook. Of course, any story has a beginning, a middle, and an end, and any literary critic can therefore trace its humble or majestic “narrative poetics.” But doing so inevitably implies something about what the Bible is and why we read it that, on reflection, really isn’t true […]

The literary approach holds a particular appeal for avowed secularists as well as the disillusioned consumers of modern biblical scholarship. “Despite all the things we don’t believe anymore,” they say, “there is still good reason for the Bible’s place of honor in our culture. It’s great literature!” This is not utterly false: the story of Joseph has a good plot; David is artfully limned. But from there to claiming that the Bible is Number One because of its literary qualities – puh-leeze! If its literary merit were the reason why we read it, surely the Good Book would have been swapped long ago for Dante and Shakespeare and Milton, Goethe and Dostoevsky and James Joyce. To compare the Bible’s artistic qualities to those of these authors is to compare the little tunes played on a shepherd’s pipe to the mighty sound of a symphony orchestra. Ultimately, this is just another form of apologetic, an attempt to save something special about Scripture in an unbelieving world.

Strange to tell, while many of today’s literary critics of the Bible are avowed secularists, their writings sometimes hold a particular appeal for people of rather conservative religious beliefs, Christians or Jews eager to celebrate the Bible’s merits. For them, its selling point lies not only in its capacity to push aside modern scholarship, but as well in its attribution to Scripture of a kind of artistry and design bordering on the miraculous, something that only “the great novelist in the Lord” (as Norman Mailer once put it) would be capable of composing. It might seem unfair to compare the appeal of this approach to that of a truly crackpot domain, the discovery of secret “codes” in the Bible that are held to have predicted various historical events. What both have in common, however, is their ability to convince ordinary readers, at least those eager to be convinced, that there still is something special, indeed, something deeply hidden or infinitely complicated about the Bible that fully reflects its divine origins. So, religious readers may be spotted in the admiring throng as literary critics offer up complicated diagrams showing the incredibly complex symmetry of the story of the Tower of Babel or the Jacob cycle, or the heretofore unnoticed repetition of a crucial thematic Leitwort (“key word”) in the Elijah-Elisha stories. (The diagrams are indeed symmetrical, but the texts themselves often less so; the Leitwort, alas, often turns out to be “go,” “all,” “people” or some other common term, which might be located with equal frequency in a paragraph of Samuelson’s Economics. Sad to say, one cannot escape the impression that beauty here is often solely in the eye of the pious beholder.)

Beyond all these is one more, somewhat less obvious, apologetic aspect to today’s literary criticism of the Bible. Such criticism is quite often predicated on what, in another context, has been called “The View from Nowhere.” That is, today’s literary critics offer highly sophisticated arguments about the subtleties of this or that part of the Bible, but if you were to ask them who it was who created the subtleties, they have no plausible answer to offer, since the aims and methods of these same biblical authors or redactors must be found elsewhere to be (at least if these critics are honest) quite at odds with the aims and methods implied by their literary analysis. So these wonderful literary subtleties just are; they came from nowhere at all […]“

Kugel develops his critique very convincingly, with many examples.