Talmud Yerushalmi in the Digital Age: New Frontiers in the Overlooked Talmud

Compare my somewhat related review at the Seforim Blog, “From Print to Pixel: Digital Editions of the Talmud Bavli” (June 5, 2023),

Outline

Historical Background

A Tale of Two Talmudim

Pre-Modern and Traditional Study of the Yerushalmi

The Rise of the Modern Study of Yerushalmi

Early 20th Century: The Philological Turn

Late 20th and 21st Century: The Yerushalmi as a Window into Late Antiquity

The Need for a Critical Edition

The Katz Edition: A Digital Edition

The Digital Scholarly Edition

Screenshots of Major Features in the Edition

Digital Editions: Current State and Future Prospects

A Tale of Two Talmudim

Whenever someone speaks of “the Talmud,” you can be almost certain they mean the Babylonian Talmud (or “Talmud Bavli”). This is true even for scholarly works.1 This is rather odd, because there have always been two Talmudim: the Talmud of Babylonia, and the Talmud of Eretz Yisrael, also known as the Jerusalem Talmud.2

We will not discuss here the historical circumstances that contributed to the rise of the Babylonian Talmud.3 The fact remains that the Jerusalem Talmud was neglected for centuries. While its Babylonian counterpart became the dominant text of rabbinic discourse, the Yerushalmi was not widely studied, lacked authoritative commentary, and suffered from a fragmentary manuscript tradition that sometimes made reconstructing a reliable text nearly impossible.4

Why was this the case? Unlike the Bavli, which was carefully copied and studied by generations of talmidei chachamim, the Yerushalmi never had a robust chain of transmission. It was redacted in Eretz Yisrael towards the end of the 4th century CE,5 but it fell out of widespread use following the decline of Jewish life in the region. By the time later scholars sought to recover it, they had only a handful of flawed manuscripts to work with.

Saul Lieberman states in Ha-Yerushalmi Ki-Fshuto, p. 7:

One of the leading recent commentators, the gaon R. Meir Meirim [Shafit], of blessed memory, wrote on the Jerusalem Talmud and the difficulties entailed in its study in his book Nir:

" 'The hills are around Jerusalem' ( ירושלים הרים סביב לה): high and steep hills, rocky clefts, alluding to its concise wordings, etc."

He did not exaggerate in his description, for when we engage deeply with the sugyot of the Jerusalem Talmud, we are at a total loss: all is vague and closed, there is none to close or open, none to interpret or explain.

Pre-Modern and Traditional Study of the Yerushalmi

Before the modern era, the study of the Yerushalmi was sporadic. Some Rishonim engaged with it, but it was considered secondary to the Babylonian Talmud, to say the least. Many scholars rarely used it, and probably did not have it in their bookshelf. Rashi, for example, cites it in its monumental commentary to the Bavli, no more than a few dozen times, and it is not sure how many of the citations were made by Rashi and how many were added to the commentary in later stages.6

Some Rishonim, like Rabbenu Hannanel (North Africa, 11th century), Rambam (Spain and North Africa, the second half of the 11th century), Ramban (Spain, 12th century) and R. Yitzhak of Vienna (13th century) used it more extensively but those remained the outlier. Manuscripts of the Yerushalmi were most certainly rare.7 Notably, no Rishon wrote a commentary on the Yerushalmi, even though many commentaries and Chidushim were written on the Bavli.

The 16th-century publication of the editio princeps (first edition, by Bomberg in Venice, 1523-1524) brought greater accessibility.8

The printing of the Yerushalmi marked a turning point, as more scholars began to study it and write commentaries - beginning with R. Shlomo Sirilio (Eretz Yisrael, 16th century), who was the first to write a commentary on the Yerushalmi (Seder Zeraim), alongside his contemporary R. Elazar Azikri (on tractates Berakhot and Betza).

Later the Pnei Moshe (R. Moshe Margolis, 18th century) and the Korban Ha-Edah (R. David Frankel), whose more extensive commentaries became the standard for hundreds of years.

The Rise of the Modern Study of Yerushalmi

In the 19th century, some scholars sought to approach the Yerushalmi with a firmer historical and textual methodology. This period saw significant advances in understanding its distinctive language, manuscripts, and relationship to other sources.

Among the most important 19th-century scholars were Zacharias Frankel (1801-1875), who wrote an important introduction to the Yerushalmi,9 and his devoted student Israel Lewy (1841-1917), who was the first to recognize the uniqueness of Yerushalmi Nezikin.10 Their scholarly contributions were particularly significant. On the rabbinical side, the great work of Yefeh Enayim by R. Aryeh Leib Yellin (1820-1886), who collected the parallels between the Bavli and Yerushalmi, deserves special mention.

Another notable scholar was R. Dov Ber Ratner (1852-1917). His work was pioneering in several ways, including detailed analysis of parallel sugyot in the Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmuds. However, despite the importance of his work, it should be noted that his approach was somewhat problematic. His eagerness to find faults in our version of Yerushalmi based on citations from early rabbinical authorities and textual variants sometimes led him astray. In many cases, his conclusions don't stand up to criticism, as noted by Prof. Yaakov Sussman.11

Early 20th Century: The Philological Turn

As historical and textual studies of rabbinic literature progressed, Yerushalmi scholarship became increasingly scientific. Key developments included:

Textual Editing & Manuscripts: The Leiden Manuscript (Codex Scaliger 3) became central to scholarly editions. Though this manuscript was already known in the 19th century, its value was often underappreciated. Scholars who paid particular attention to it were mainly Yaakov Nahum Epstein and Saul Lieberman.

Yaakov Nahum Epstein (1878-1952): a towering figure in Talmudic philology, revolutionized the field. His work emphasized:

The Yerushalmi's linguistic and textual stratification

Its connection to Tannaitic literature, especially the Tosefta

The oral transmission of Amoraic traditions

Careful textual analysis based on the best manuscripts

Saul Lieberman (1898-1983): One of the great modern scholars of the Yerushalmi, Lieberman's work included:

His Tosefta Kifshuta and Yerushalmi Kifshuto, which used the Yerushalmi to reconstruct early halakhic traditions12

His analysis of the Greco-Roman background in the culture of Eretz Yisrael13

Important early works like "On the Yerushalmi" (על הירושלמי), where he addressed textual corrections and collected textual variants14

"Talmud of Caesarea" (תלמודה של קיסרין) where he suggested that the Nezikin tractate originated in Caesarea

Late 20th and 21st Century: The Yerushalmi as a Window into Late Antiquity

The Yerushalmi is now studied not only as a halakhic source but as a major historical document. Key themes include:

Sociopolitical Context: Scholars such as Lee Levine and Seth Schwartz have used the Yerushalmi to study Roman Eretz Yisrael.15

Comparative Talmudics: The Bavli-Yerushalmi relationship remains a key focus, with scholars analyzing why certain sugyot appear in both, differ, or are missing.16

Linguistic Studies: The Aramaic dialect of the Yerushalmi is studied by linguists to understand it on its own, as distinct from Babylonian Aramaic.17

Recent critical editions, such as that by the Academy of the Hebrew Language (see more on this below), provide a more reliable text. It should be noted that while Dikdukei Sofrim HaShalem by Yad HaRav Herzog provides critical editions for the Babylonian Talmud, it does not cover the Yerushalmi.

However, there remains a major need for a comprehensive edition of the Talmud Yerushalmi that would include a corrected text, parallels, citations, and other scholarly apparatus. While many works from rabbinic literature already have several editions (for example, midreshei halacha and midreshei aggadah), this shortage is particularly noticeable in both Talmuds, especially the Yerushalmi.

The Need for a Critical Edition

It is very hard to study a text without knowing exactly what that text is. Since the current printed editions are reproductions (with errors and “corrections”) of the first printed edition, one cannot use them as the main source of information regarding the Yerushalmi. Oddly enough, the first printed edition cannot be regarded as a primary textual witness of the Yerushalmi, since we know which manuscript it was copied from - the Leiden Manuscript, which was copied in Italy in 1289. We know that because we have the notes of the Venice printers and proofreaders on the leaves of the manuscript.

This, and the unfortunate fact that the Leiden manuscript is in many cases the only source of the Yerushalmi text, led the Academy of the Hebrew Language to produce a diplomatic edition—a transcription of the Leiden manuscript with minimal emendation, preserving its textual idiosyncrasies. Thus we had, for the first time, some sort of scholarly edition of the Yerushalmi. Nevertheless, while this was a major step forward, it wasn't a full scholarly edition:18

It does not systematically compare other textual witnesses, such as Genizah fragments or medieval citations

It does not attempt to reconstruct the most accurate version of the text

It does not provide full scholarly apparatuses that would enable deeper study

Thus, while useful, the Leiden diplomatic edition alone isn't sufficient for proper scholarly engagement with the Yerushalmi.

The Katz Edition: A Digital Edition

This gap is currently being addressed by Prof. Menachem Katz, a researcher at The Open University of Israel and The DHSS Hub (Center for Digital Humanities and Social Sciences). Katz has extensive experience in Talmudic textual scholarship and digital humanities, including work at the Saul Lieberman Institute for Talmudic Research and the Friedberg Jewish Manuscript Society (FJMS).

Katz's work on the Yerushalmi began in 2016 with the publication of a scholarly edition of Tractate Kiddushin. Building on that foundation, he has developed the Digital Scholarly Edition of the Jerusalem Talmud at TalmudYerushalmi.com.

The Digital Scholarly Edition

This new edition aims to provide a comprehensive scholarly reconstruction of the text, based on manuscripts, Genizah fragments, medieval citations, and internal textual analysis. The platform features:

A reconstructed text with indications of corrections and emendations

A scholarly apparatus including Talmudic parallels, medieval citations, and bibliographic references

Integrated manuscript images for comparison with primary sources

Textual variants for analyzing different readings

Interactive commentary tools

Bilingual interface in Hebrew and English

The project has made significant progress in recent years. Currently, the entire Tractate Yevamot has been translated into Hebrew—a development that was recently mentioned at an evening of study dedicated to Saul Lieberman but has not yet been widely publicized.

Additionally, a successful pilot for English translation has been conducted, with plans to create a new English translation based on their critical edition, as existing translations are inadequate for scholarly purposes (Katz, personal communication).

Screenshots of Major Features in the Edition

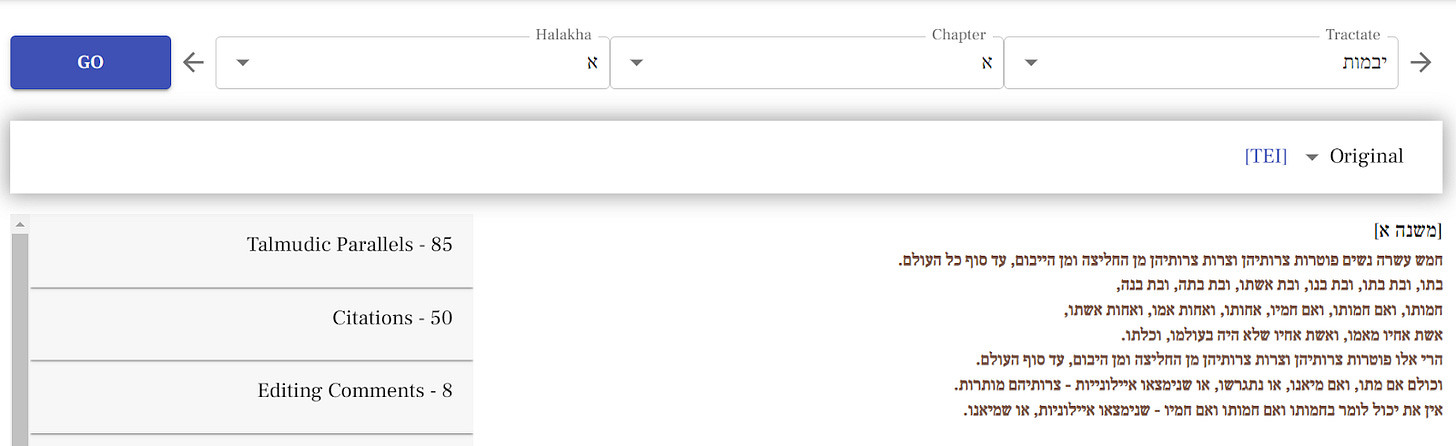

(The screenshot is from Tractate Yevamot, Chapter 1, Halakha 1)

Navigation Tools:

A navigation bar at the top allows users to select a specific tractate, chapter, and halakha.

Text Display:

The main text section prominently displays the original Hebrew text of the Yerushalmi.

The text is well-formatted, making it suitable for scholarly use.

Textual Layers:

The platform allows switching between different textual representations or formats (using a standardized digital encoding format - Text Encoding Initiative [TEI]).

In the "Synopsis" section, the platform includes manuscript comparisons, with "ל" representing the Leiden Manuscript.

(Screenshot of the left side panel, from the same page)

Expandable Panels:

Multiple categorized panels provide access to supplementary information:

Talmudic Parallels: Corresponding passages within the Talmud.

Citations: References to other sources or works that cite the passage.

Editing Comments: Editorial annotations explaining textual decisions.

Bibliographic Notes: References to relevant bibliographic materials.

Explanatory Notes: Clarifications or commentary on the text.

Dictionary: Definitions of terms within the passage.

Linked Resources:

Specific entries (e.g., פטר and ואיקפיד) are linked, providing detailed information such as definitions and context.

Digital Editions: Current State and Future Prospects

While the digital edition represents a significant advancement in Yerushalmi scholarship, it remains a work in progress with both strengths and limitations. The digital format offers clear advantages in accessibility and interactivity, but the scholarly community will need to evaluate its accuracy, methodology, and comprehensiveness as more tractates are completed.

The project exemplifies the potential of digital humanities approaches to classical texts, setting methodological precedents for other scholarly editions. The intersection of traditional philological methods with digital tools represents an important frontier in Jewish textual scholarship, one that will hopefully continue to bridge the historical gap between the extensive study of the Bavli and the relative neglect of the Yerushalmi.

Such as the latest book called The Talmud by Y. Z. Meyer and Y. Rosen-Tzvi (in Hebrew; Jerusalem: Magnes, 2025), which focuses on the Babylonian Talmud.

As an aside, that book is excellent, especially for it extensive and clear description of the typical sugya.

It’s worth noting that “Talmud Yerushalmi” is technically a misnomer: it was compiled and edited in Tiberias—perhaps partly in Caesarea—but certainly not in Jerusalem, which in the Talmudic era was virtually devoid of Jews.

The above-mentioned Meyer and Rosen-Tzvi’s book is a great starting point to learn about the subject.

For some general bibliographical overviews of the Talmud Yerushalmi, and scholarship on it, see:

L. Moscovitz (January 12, 2021). "Palestinian Talmud/Yerushalmi". Oxford Bibliographies Online.

B.M. Bokser, "An Annotated Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Palestinian Talmud"

More specifically: around 370-380 CE, according to current scholarly consensus.

See A. Grossman,The Early Sages of France (Hebrew), Jerusalem 1995, p. 247, n. 389:

Without a careful study of the manuscripts, it is difficult to determine which citations from the Yerushalmi originated with Rashi and which were added by copyists and inserted into his wording. Nevertheless, it is clear that Rashi used the Talmud Yerushalmi, albeit very rarely.

See also R. Reiner, “The Yerushalmi in Rabbeinu Tam’s Library”, REJ 178 (2019).

To illustrate, in Y. Sussman’s Thesaurus of Talmudic Manuscripts (Jerusalem, 2012. The count here follows the updated version on the fjms.org portal) only 181 full or partial manuscripts of Yerushalmi are cataloged, compared to 2,924 of the Bavli.

Even after accounting for the difference in length between the two Talmudim (the Bavli, at 1.74 million words, is about twice the size of the Yerushalmi, about 889k words - see my piece “Words of Wisdom: Word Counts of Classical Jewish Works”), the numbers are striking.

On this edition, see this recent major piece of scholarship: Y. Z. Mayer, Editio Princeps: The 1523 Venice Edition of the Palestinian Talmud and the Beginning of Hebrew Printing, Jerusalem: Magnes, 2022.

Mevo HaYerushalmi, Breslau 1870.

The first part of Lewy’s commentary on Yerushalmi Neziqin was published in 1895, marking what Y. Sussmann called “a new era of the critical commentary of the Talmud Yerushalmi” (“Again Concerning Yerushalmi Neziqin [Veshuv Li-Yerushalmi Neziqin],” in Y. Sussmann and D. Rosenthal [eds.], Meḥqere Talmud I, Jerusalem: Magnes, 1990, p. 55).

See there, note 3, for an admiring assessment of Lewy’s new critical methods.

“The Yerushalmi in the Literature of the Rishonim: 100 Years after "Ahavat Zion ViYerushalaim"”, Jewish Studies 41 (2002), pp.17-28.

See: ש' ליברמן, הירושלמי כפשוטו, ירושלים, תרצ"ה; מהדורה מתוקנת, תשס"ח

See: ש' ליברמן, יוונית ויוונות בארץ ישראל, ירושלים, תשכ"ג (1962)

See: מ' עסיס, גליונות הירושלמי של רבי שאול ליברמן, שלושה כרכים, ירושלים, תשפ"ב (2022).

See S. Stern, "The Talmud Yerushalmi," In: M. Goodman and P. Alexander (eds.), Rabbinic Texts and the History of Late-Roman Palestine (Oxford, 2010), 143–164

See:

ל' מוסקוביץ, “סוגיות מקבילות ומסורת-נוסח הירושלמי”, תרביץ ס, תשנ"א, עמ' 549-523.

ד' רוזנטל, "תורת ארץ-ישראל בתלמוד הבבל", בתוך: כהנא, נעם, קיסטר, רוזנטל (עורכים): ספרות חז"ל הארץ-ישראלית – מבואות ומחקרים, כרך ראשון, 2018, עמ' 296-261

See:

M. Sokoloff, A Dictionary of Jewish Palestinian Aramaic, Ramat Gan, 2017

מ' עסיס, אוצר לשונות ירושלמיים, א-ג, ניו-יורק וירושלים, תש"ע (2010).

ל' מוסקוביץ, הטרמינולוגיה של הירושלמי, המונחים העיקריים, ירושלים, תשס"ט (2009)

Compare: ש' נאה, “תלמוד ירושלמי במהדורת האקדמיה ללשון העברית”, תרביץ עא, תשס"ב, עמ' 603-569

Thanks for an informative post. Footnote 9 refers to Sussman's "admiring assessment of Lewy's critical methods". That note only contains bibliographical information.