Talmudic Interpretations of the Book of Esther: Esther 5:6-6:10 (Megillah 15b-16a)

Part of a series on the extended aggadic sugya in Tractate Megillah 10b-17a. See the previous installments here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here. Happy Purim!

The Talmudic interpretation of the Book of Esther offers a multi-layered reading blending political strategy, theological perspectives, and literary analysis. The discussion in Megillah 15b–16a provides commentary on key episodes from Esther 5:6–6:10, where Esther invites Haman to a banquet, Ahasuerus experiences a sleepless night, and the king ultimately orders Mordecai to be honored.

The Talmudic rabbis probe Esther’s motivations, providing twelve distinct explanations for why she included Haman in her banquet, ranging from psychological manipulation to divine intervention. They analyze Ahasuerus’ ambiguous offer of “half the kingdom,” interpreting it as a refusal to allow the rebuilding of the Temple.1 Haman’s downfall is foreshadowed through literary cues, including his own preparation of gallows and his attempts to minimize Mordecai’s reward.

The passage also engages in theological speculation, such as whether “the king’s sleep was disturbed” (Esther 6:1) refers to Ahasuerus or to God Himself. Even seemingly minor details, like the recording of Mordecai’s past deeds in the royal chronicles, are examined through a lens of divine orchestration, with the angel Gabriel rewriting erased records.

Outline

The Limits of Ahasuerus’ Offer (Esther 5:6): rebuilding the Temple

Esther’s Invitation to Haman (Esther 5:4): Twelve Opinions as to why Esther invited Haman to her banquet (Psalms 69:23; Proverbs 25:21, 16:18; Jeremiah 51:39)

Elijah's Confirmation: Esther was motivated by all the interpretations offered

The Fate of Haman’s Sons (Esther 5:11): died, hanged, or became beggars; Number of Haman’s Sons - 30, 70, or 208 (I Samuel 2:5)

Interpretations of the King's Sleeplessness (Esther 6:1): God, heavenly beings, the Jewish people, or Ahasuerus

Ahasuerus’ Sleepless Night and His Suspicions (Esther 6:1)

Miraculous Reading of the Chronicles (Esther 6:1-2): Shimshai, an anti-Jewish scribe, tried to erase Mordecai’s deeds, but the angel Gabriel rewrote them

The Servants’ Motivation (Esther 6:3): not out of love for Mordecai but rather due to the servants’ hatred of Haman

Haman's Intended Gallows (Esther 6:4): foreshadowing his own downfall

Ahasuerus Commands Haman to Honor Mordecai (Esther 6:10): Haman feigns ignorance, asking which Mordecai the king means

Haman's Backfired Attempt to Reduce the Honor Accorded to Mordecai (Esther 6:10)

Appendix - Analysis of Explanations for Esther's Invitation to Haman

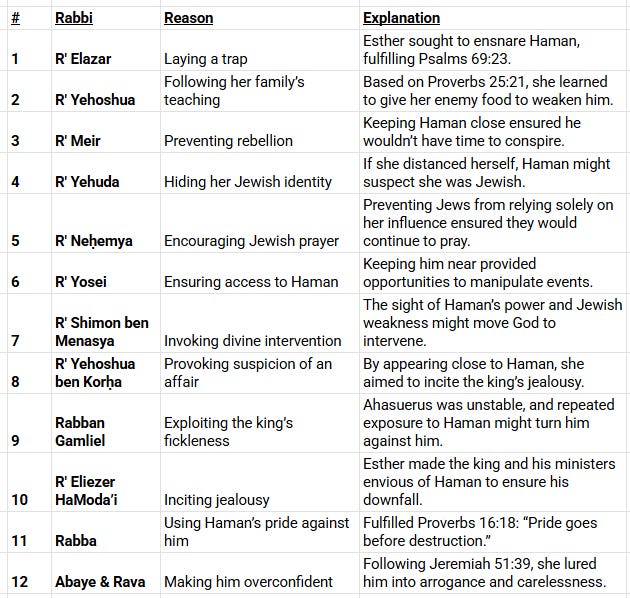

Summary Table: Twelve Reasons for Esther's Invitation to Haman

Classifying the Theories Behind Esther's Invitation to Haman: Strategic Entrapment, Political Maneuvering, Psychological Tactics, Concealment and Protection, and Divine Intervention

A Trap for Haman

Political and Psychological Interpretations: the psychology of Esther and the Jews

The Passage

The Limits of Ahasuerus’ Offer (Esther 5:6): rebuilding the Temple

The verse states that Ahasuerus offered Esther anything up to “half the kingdom (מלכות)”.

The Talmud interprets this to mean that he would not grant anything that could divide2 the kingdom, specifically the rebuilding of the Temple.

״ויאמר לה המלך לאסתר המלכה:

מה בקשתך?

עד חצי המלכות, ותעש״.

"חצי המלכות" --

ולא כל המלכות,

ולא דבר שחוצץ למלכות,

ומאי ניהו?

בנין בית המקדש.

The verse states: “Then the king said to her” (Esther 5:3), to Esther the queen,

“What is your wish?

even to half the kingdom, it shall be performed” (Esther 5:6).

The Gemara comments that Ahasuerus intended only a limited offer: Only half the kingdom,

but not the whole kingdom,

and not something that would serve as a barrier to the kingdom, as there is one thing to which the kingdom will never agree.

And what is that?

The building of the Temple; if that shall be your wish, realize that it will not be fulfilled.

Esther’s Invitation to Haman (Esther 5:4): Twelve Opinions as to why Esther invited Haman to her banquet (Psalms 69:23; Proverbs 25:21, 16:18; Jeremiah 51:39)

The Talmud lists twelve different theories on why Esther invited Haman to her banquet:3

Laying a Trap (R' Elazar) – Esther sought to ensnare Haman, fulfilling the verse: "Let their table become a snare (פח) before them" (Psalms 69:23).

Following Her Family's Teaching (R' Yehoshua) – She acted in accordance with "If your enemy is hungry, give him bread to eat" (Proverbs 25:21), a lesson she learned from her father’s house.

Preventing Rebellion (R' Meir) – Keeping Haman close ensured he would not have the opportunity to conspire to rebel (against Ahasuerus).

Hiding Her Jewish Identity (R' Yehuda) – By keeping Haman close, she avoided raising suspicion about her Jewish/Judean (יהודית) heritage.

Encouraging Jewish Prayer (R' Neḥemya) – If the Jews relied on Esther’s influence,4 they might neglect (יסיחו דעתן) their prayers for divine mercy (so she ensured they would not see her as their sole hope).

Ensuring Access to Haman (R' Yosei) – Having Haman constantly (בכל עת) near her provided an opportunity to cause his downfall before the king.

Invoking Divine Intervention (R' Shimon ben Menasya) – Seeing the Jews forsaken and Haman supported by all, God might be moved to perform a miracle.

Provoking Suspicion of an Affair (R' Yehoshua ben Korḥa) – By acting warmly (אסביר לו פנים) toward Haman, she aimed to arouse the king’s jealousy, leading to both her and Haman’s death (thereby ensuring the decree against the Jews would be annulled).

Exploiting the King’s Fickleness (Rabban Gamliel) – Ahasuerus was fickle (הפכפכן - and repeated exposure to Haman could lead him to change his opinion of him).

Inciting Jealousy (R' Eliezer HaModa’i) – Esther manipulated the king and his ministers (שרים) into resenting Haman, which ultimately led to his downfall.

Using Haman’s Pride Against Him (Rabba) – She fulfilled the verse "Pride (גאון) goes before destruction (שבר)" (Proverbs 16:18), leading to Haman’s downfall.

Making Him Overconfident (Abaye and Rava) – She followed "When they are heated (חומם), I will make feasts for them, and I will make them drunk, that they may rejoice, and sleep a perpetual sleep" (Jeremiah 51:39 - ensuring Haman’s downfall through his own arrogance).

.״יבא המלך והמן אל המשתה״.

תנו רבנן:

מה ראתה אסתר שזימנה את המן?

רבי אלעזר אומר: פחים טמנה לו,

שנאמר: ״יהי שלחנם לפניהם לפח״.

רבי יהושע אומר: מבית אביה למדה,

שנאמר: ״אם רעב שונאך, האכילהו לחם וגו׳״.

רבי מאיר אומר: כדי שלא יטול עצה וימרוד.

רבי יהודה אומר: כדי שלא יכירו בה שהיא יהודית.

רבי נחמיה אומר: כדי שלא יאמרו ישראל: אחות יש לנו בבית המלך, ויסיחו דעתן מן הרחמים.

רבי יוסי אומר: כדי שיהא מצוי לה בכל עת.

רבי שמעון בן מנסיא אומר: אולי ירגיש המקום, ויעשה לנו נס.

רבי יהושע בן קרחה אומר: אסביר לו פנים, כדי שיהרג הוא והיא.

רבן גמליאל אומר: מלך הפכפכן היה.

אמר רבי גמליאל: עדיין צריכין אנו למודעי, דתניא, רבי אליעזר המודעי אומר: קנאתו במלך, קנאתו בשרים.

רבה אמר: ״לפני שבר גאון״.

אביי ורבא דאמרי תרוייהו: ״בחומם, אשית את משתיהם וגו׳״

The verse states that Esther requested: “If it seem good unto the king, let the king and Haman come this day to the banquet that I have prepared for him” (Esther 5:4).

The Sages taught in a baraita: What did Esther see to invite Haman to the banquet?

R' Elazar says: She hid a snare for him,

as it is stated: “Let their table become a snare before them” (Psalms 69:23), as she assumed that she would be able to trip up Haman during the banquet.

R' Yehoshua says: She learned to do this from the Jewish teachings of her father’s house,

as it is stated: “If your enemy be hungry, give him bread to eat” (Proverbs 25:21).

R' Meir says: She invited him in order that he be near her at all times, so that he would not take counsel and rebel against Ahasuerus when he discovered that the king was angry with him.

R' Yehuda says: She invited Haman so that it not be found out that she was a Jew, as had she distanced him, he would have become suspicious.

R' Neḥemya says: She did this so that the Jewish people would not say: We have a sister in the king’s house, and consequently neglect their prayers for divine mercy.

R' Yosei says: She acted in this manner, so that Haman would always be on hand for her, as that would enable her to find an opportunity to cause him to stumble before the king.

R' Shimon ben Menasya said that Esther said to herself: Perhaps the Omnipresent will take notice that all are supporting Haman and nobody is supporting the Jewish people, and He will perform for us a miracle.

R' Yehoshua ben Korḥa says: She said to herself: I will act kindly toward him and thereby bring the king to suspect that we are having an affair; she did so in order that both he and she would be killed. Essentially, Esther was willing to be killed with Haman in order that the decree would be annulled.

Rabban Gamliel says: Ahasuerus was a fickle king, and Esther hoped that if he saw Haman on multiple occasions, eventually he would change his opinion of him.

Rabban Gamliel said: We still need the words of R' Eliezer HaModa’i to understand why Esther invited Haman to her banquet. As it is taught in a baraita: R' Eliezer HaModa’i says: She made the king jealous of him and she made the other ministers jealous of him, and in this way she brought about his downfall.

Rabba says: Esther invited Haman to her banquet in order to fulfill that which is stated: “Pride goes before destruction” (Proverbs 16:18), which indicates that in order to destroy the wicked, one must first bring them to pride.

Abaye and Rava both say that she invited Haman in order to fulfill the verse: “When they are heated, I will make feasts for them, and I will make them drunk, that they may rejoice, and sleep a perpetual sleep” (Jeremiah 51:39).

Elijah's Confirmation: Esther was motivated by all the interpretations offered

Rabba bar Avuha encounters Elijah and asks which explanation (for Esther's motivations for inviting Haman) is correct. Elijah responds that Esther was motivated by all (twelve) interpretations listed in the previous section.5

אשכחיה רבה בר אבוה לאליהו,

אמר ליה: כמאן חזיא אסתר ועבדא הכי?

אמר ליה: ככולהו תנאי וככולהו אמוראי.

The Gemara relates that Rabba bar Avuh once happened upon Elijah the Prophet

and said to him: In accordance with whose understanding did Esther see fit to act in this manner? What was the true reason behind her invitation?

He, Elijah, said to him: Esther was motivated by all the reasons previously mentioned and did so for all the reasons previously stated by the tanna’im and all the reasons stated by the amora’im.

The Fate of Haman’s Sons (Esther 5:11): died, hanged, or became beggars; Number of Haman’s Sons - 30, 70, or 208 (I Samuel 2:5)

The Talmud examines the phrase “the multitude of his sons” (Esther 5:11) and questions how many sons Haman had in total.

Rav states that Haman had 30 sons: 10 died in childhood, 10 were hanged (as recorded later in the Book of Esther), and 10 survived but were forced to beg for food.6

Other rabbis argue that the number of sons who begged for food was 70. They derive this from a reinterpretation of I Samuel 2:5, changing the word seve’im (שבעים - "full") to “shiv’im” ("seventy"), suggesting that seventy of Haman’s descendants were impoverished.

Rami bar Abba claims that Haman had 208 sons, based on the numerical value (gematria) of the word “ve-rov” (ורוב - "and the multitude").

The Talmud points out that “ve-rov” in gematria equals 214, not 208. Rav Naḥman bar Yitzḥak resolves this by noting that the word is written in the biblical text without a second vav (ורב), reducing its numerical value to 208.

״ויספר להם המן את כבוד עשרו ורוב בניו״,

וכמה רוב בניו?

אמר רב:

שלשים:

עשרה מתו,

ועשרה נתלו,

ועשרה מחזרין על הפתחים.

ורבנן אמרי:

אותן שמחזרין על הפתחים שבעים היו,

דכתיב: ״שבעים בלחם נשכרו״,

אל תקרי ״שבעים״ אלא ״שבעים״.

ורמי בר אבא אמר:

כולן מאתים ושמונה הוו,

שנאמר: ״ורוב בניו״.

״ורוב״ בגימטריא מאתן וארביסר הוו!

אמר רב נחמן בר יצחק: ״ורב״ כתיב.

The verse states: “And Haman recounted to them the glory of his riches, and the multitude of his sons” (Esther 5:11).

The Gemara asks: And how many sons did he in fact have that are referred to as “the multitude of his sons”?

Rav said: There were thirty sons:

ten of them died in childhood,

ten of them were hanged as recorded in the book of Esther,

and ten survived and were forced to beg at other people’s doors.

And the Rabbis say:

Those that begged at other people’s doors numbered seventy,

as it is written: “Those that were full, have hired themselves out for bread” (I Samuel 2:5).

Do not read it as: “Those that were full” [seve’im]; rather, read it as seventy [shivim], indicating that there were seventy who “hired themselves out for bread.”

And Rami bar Abba said:

All of Haman’s sons together numbered two hundred and eight,

as it is stated: “And the multitude [verov] of his sons.” The numerical value of the word verov equals two hundred and eight, alluding to the number of his sons.

The Gemara comments: But in fact, the numerical value [gimatriyya] of the word verov equals two hundred and fourteen, not two hundred and eight.

Rav Naḥman bar Yitzḥak said: The word verov is written in the Bible without the second vav, and therefore its numerical value equals two hundred and eight.

Interpretations of the King's Sleeplessness (Esther 6:1): God, heavenly beings, the Jewish people, or Ahasuerus

The verse "On that night the sleep of the king was disturbed" (Esther 6:1) is interpreted in multiple ways:

R' Tanḥum states that it refers to God (מלכו של עולם).

The rabbis (רבנן) suggest that both heavenly beings (עליונים) and the Jewish people (תחתונים) were restless.

Rava, however, insists that the verse refers simply to King Ahasuerus himself.

״בלילה ההוא נדדה שנת המלך״.

אמר רבי תנחום: נדדה שנת מלכו של עולם.

ורבנן אמרי: נדדו עליונים, נדדו תחתונים.

רבא אמר: שנת המלך אחשורוש ממש.

The verse states: “On that night the sleep of the king was disturbed” (Esther 6:1).

R' Tanḥum said: The verse alludes to another king who could not sleep; the sleep of the King of the universe, the Holy One, Blessed be He, was disturbed.

And the Sages say: The sleep of the higher ones, the angels, was disturbed, and the sleep of the lower ones, the Jewish people, was disturbed.

Rava said: This should be understood literally: The sleep of King Ahasuerus was disturbed.

Ahasuerus’ Sleepless Night and His Suspicions (Esther 6:1)

Ahasuerus is unable to sleep because a troubling thought enters his mind.

He wonders why Esther has invited Haman to her banquet and suspects a possible conspiracy against him.

He questions whether he has any loyal supporters who would warn him of such a plot.

He then considers whether he has failed to reward someone who had helped him, which might explain why no one informs him of threats.

To investigate, he orders the royal chronicles7 to be brought and examined (Esther 6:1).

נפלה ליה מילתא בדעתיה,

אמר: מאי דקמן דזמינתיה אסתר להמן?

דלמא עצה קא שקלי עילויה דההוא גברא למקטליה?!

הדר אמר: אי הכי, לא הוה גברא דרחים לי, דהוה מודע לי?!

הדר אמר:

דלמא איכא איניש דעבד בי טיבותא, ולא פרעתיה?!

משום הכי מימנעי אינשי, ולא מגלו לי,

מיד: ״ויאמר להביא את ספר הזכרונות דברי הימים״.

And this was the reason Ahasuerus could not sleep: A thought occurred to him

and he said to himself: What is this before us that Esther has invited Haman?

Perhaps they are conspiring against that man, i.e., against me, to kill him?!

He then said again to himself: If this is so, is there no man who loves me and would inform me of this conspiracy?!

He then said again to himself:

Perhaps there is some man who has done a favor for me and I have not properly rewarded him?!

and due to that reason people refrain from revealing to me information regarding such plots, as they see no benefit for themselves.

Immediately afterward, the verse states: “And he commanded the book of remembrances of the chronicles to be brought” (Esther 6:1).

Miraculous Reading of the Chronicles (Esther 6:1-2): Shimshai, an anti-Jewish scribe, tried to erase Mordecai’s deeds, but the angel Gabriel rewrote them

The chronicles are read aloud to Ahasuerus, and the text states that they "were read"8 rather than "were read to him”. The Talmud explains that the passive phrasing implies a miraculous event— the records were read on their own, without human intervention.

The verse states “And it was found written” (Esther 6:2), using the word katuv, which suggests something being actively written. The Talmud questions why the term ketav (a past writing) was not used instead.

The Talmud explains that Shimshai (שמשי), an anti-Jewish scribe (see Ezra 4:9–10), kept erasing Mordecai’s act of saving the king, but the angel Gabriel continuously rewrote it. (This justifies the present-tense implication of katuv—it was actively being rewritten.)

R' Asi cites R' Sheila from Timarta, who draws a broader conclusion: If a record written in this world for the benefit of the Jewish people cannot be erased, then surely this principle applies even more so in the divine realm (למעלה).

״ויהיו נקראים״ —

מלמד שנקראים מאיליהן.

״וימצא כתוב״ —

״כתב״ מבעי ליה?

מלמד:

ששמשי מוחק

וגבריאל כותב.

אמר רבי אסי:

דרש רבי שילא איש כפר תמרתא:

ומה כתב שלמטה שלזכותן של ישראל — אינו נמחק,

כתב שלמעלה — לא כל שכן?!

The verse states: “And they were read before the king” (Esther 6:1).

The Gemara explains that this passive form: “And they were read,” teaches that they were read miraculously by themselves.

It further says: “And it was found written [katuv]” (Esther 6:2).

The Gemara asks: Why does the Megilla use the word katuv, which indicates that it was newly written? It should have said: A writing [ketav] was found, which would indicate that it had been written in the past.

The Gemara explains: This teaches that

Shimshai, the king’s scribe who hated the Jews (see Ezra 4:17), was erasing the description of Mordecai’s saving the king,

and the angel Gavriel was writing it again. Therefore, it was indeed being written in the present.

R' Asi said:

R' Sheila, a man of the village of Timarta, taught:

If something written down below in this world that is for the benefit of the Jewish people cannot be erased,

is it not all the more so the case that something written up above in Heaven cannot be erased?!

The Servants’ Motivation (Esther 6:3): not out of love for Mordecai but rather due to the servants’ hatred of Haman

Ahasuerus asks whether Mordecai was ever rewarded and learns that "nothing has been done for him."

Rava notes that this response was not out of love for Mordecai but rather due to the servants’ hatred of Haman.

״לא נעשה עמו דבר״.

אמר רבא:

לא מפני שאוהבין את מרדכי,

אלא מפני ששונאים את המן.

The verse states that Ahasuerus was told with regard to Mordecai: “Nothing has been done for him” (Esther 6:3).

Rava said:

It is not because they love Mordecai that the king’s servants said this,

but rather because they hate Haman.

Haman's Intended Gallows (Esther 6:4): foreshadowing his own downfall

The verse states that Haman had prepared gallows for Mordecai, but a baraita clarifies that he had actually prepared them for himself. This foreshadows Haman’s downfall.

״הכין לו״.

תנא: לו הכין.

The verse states: “Now Haman had come into the outer court of the king’s house, to speak to the king about hanging Mordecai on the gallows that he had prepared for him” (Esther 6:4).

A Sage taught in a baraita: This should be understood to mean: On the gallows that he had prepared for himself.

Ahasuerus Commands Haman to Honor Mordecai (Esther 6:10): Haman feigns ignorance, asking which Mordecai the king means

When Ahasuerus orders Haman to honor Mordecai, Haman feigns ignorance, asking which Mordecai the king means.9

Ahasuerus clarifies that he means Mordecai “the Jew” and further specifies him as the one “who sits at the king’s gate.”

״ועשה כן למרדכי״.

אמר ליה: מנו מרדכי?

אמר ליה: ״היהודי״.

אמר ליה: טובא מרדכי איכא ביהודאי.

אמר ליה: ״היושב בשער המלך״.

The verse relates that Ahasuerus ordered Haman to fulfill his idea of the proper way to honor one who the king desires to glorify by parading him around on the king’s horse while wearing the royal garments: “And do so to Mordecai the Jew who sits at the king’s gate, let nothing fail of all that you have spoken” (Esther 6:10).

The Gemara explains that when Ahasuerus said to Haman: “And do so to Mordecai,”

Haman said to him in an attempt to evade the order: Who is Mordecai?

Ahasuerus said to him: “The Jew.”

Haman then said to him: There are several men named Mordecai among the Jews.

Ahasuerus then said to him: I refer to the one “who sits at the king’s gate.”

Haman's Backfired Attempt to Reduce the Honor Accorded to Mordecai (Esther 6:10)

Haman tries to limit Mordecai’s reward, suggesting a small estate (דיסקרתא) or a river/canal (נהרא - for toll revenue).

Ahasuerus, however, insists that every detail of Haman’s proposed honor must be fulfilled, adding even more benefits for Mordecai.

אמר ליה:

סגי ליה בחד דיסקרתא,

אי נמי בחד נהרא.

אמר ליה:

הא נמי הב ליה,

״אל תפל דבר מכל אשר דברת״.

Haman said to him:

Why award him such a great honor? It would certainly be enough for him to receive one village [disekarta] as an estate,

or one river for the levy of taxes.

Ahasuerus said to him:

This too you must give him.

“Let nothing fail of all that you have spoken,” i.e., provide him with all that you proposed and spoke about in addition to what I had said.

Appendix - Analysis of Explanations for Esther's Invitation to Haman

Summary Table: Twelve Reasons for Esther's Invitation to Haman

Classifying the Theories Behind Esther's Invitation to Haman: Strategic Entrapment, Political Maneuvering, Psychological Tactics, Concealment and Protection, and Divine Intervention

This categorization highlights the various strategic, political, psychological, and religious motivations attributed to Esther’s actions:

1. Strategic Entrapment

R' Elazar – She set a trap for Haman, fulfilling Psalms 69:23.

2. Political Manipulation

R' Meir – Preventing Haman from conspiring against Ahasuerus.

R' Yosei – Keeping Haman close to create opportunities for his downfall.

R' Eliezer HaModa’i – Inciting jealousy among the king and ministers to turn them against Haman.

Rabban Gamliel – Exploiting the king’s fickle nature to make him turn on Haman.

3. Psychological Warfare

R' Yehoshua – Following Proverbs 25:21, feeding an enemy to weaken him.

R' Yehoshua ben Korḥa – Provoking suspicion of an affair to make Ahasuerus jealous.

Rabba – Increasing Haman’s arrogance, fulfilling Proverbs 16:18.

Abaye & Rava – Making Haman overconfident and careless, following Jeremiah 51:39.

4. Concealment & Protection

R' Yehuda – Preventing suspicion that she was Jewish.

R' Neḥemya – Ensuring Jews didn’t rely on her and continued praying.

5. Seeking Divine Intervention

R' Shimon ben Menasya – Hoping God would intervene when seeing Jewish weakness.

A Trap for Haman

Several interpretations revolve around the theme of setting a trap for Haman, whether literally (R' Elazar) or metaphorically (R' Meir, Rabba, Abaye, and Rava). This ties into a broader biblical motif of poetic justice: the wicked are undone by their own arrogance. Esther’s banquet becomes a reversal of fortune, a key theme in the Book of Esther itself.

Political and Psychological Interpretations: the psychology of Esther and the Jews

Some interpretations emphasize the psychology of Esther and her people:

R' Neḥemya’s view that Esther’s actions prevented complacency among the Jews highlights a communal concern: would reliance on political connections undermine divine supplication?

R' Yehuda’s suggestion that she sought to hide her Jewish identity reveals anxieties about assimilation and survival in exile.

Rabban Gamliel’s view that Ahasuerus was “fickle” (הפכפכן) suggests a cynical, pragmatic understanding of power, one that acknowledges the instability of court favor.

Meaning, to build the Second Temple, after the destruction of the First. See my note in an earlier installment (here), section “Interpretation of "Shonim" in Esther 1:7: Divine Rebuke for Misuse of Temple Vessels“, where I write, summarizing the talmudic passage earlier in this sugya:

Ahasuerus calculated that the 70 years had passed without the Jews' redemption and assumed they never would be. He then used the Temple vessels. As punishment, Satan disrupted his celebration, causing confusion that led to Vashti's death:

Refer to my Appendix for a table that summarizes the twelve opinions and categorizes the interpretations into major groups.

Saying: “We have a sister in the palace“ (אחות יש לנו בבית המלך).

The phrase “we have a sister” (אחות יש לנו) may be echoing the biblical verse in Song_of_Songs.8.8:

אחות לנו קטנה

We have a little sister

Possible intertextual influence (admittedly highly speculative):

The phrase אחות לנו קטנה from Song of Songs introduces a communal, familial concern for the sister's well-being and status, asking how she should be treated when she reaches maturity. The phrase אחות יש לנו בבית המלך reuses the structure, but the sister here is not small but positioned within a royal palace.

מחזרין על הפתחים - an idiom meaning to go door-to-door begging.

For another example of this expression, see Bava_Batra.9a.11 (part of a larger sugya on charity), where a poor man (עניא) seeking charity (מחזיר על הפתחים) approached Rav Pappa, but Rav Pappa did not help him. Rav Sama bar Yeiva rebuked Rav Pappa, warning that if he ignored the man, others would too, potentially leaving him to starve to death (לימות).

ההוא עניא דהוה מחזיר על הפתחים, דאתא לקמיה דרב פפא

לא מזדקיק ליה.

אמר ליה רב סמא בריה דרב ייבא לרב פפא:

אי מר לא מזדקיק ליה, אינש אחרינא לא מזדקיק ליה!

לימות ליה?!

It is related that a certain poor person who was going door to door requesting charity came before Rav Pappa, the local charity collector,

but Rav Pappa did not attend to him.

Rav Sama, son of Rav Yeiva, said to Rav Pappa:

If the Master does not attend to him, nobody else will attend to him either;

should he be left to die of hunger?!

Another example, Ketubot.67a.13 where a baraita states that when both an orphan boy and an orphan girl request support from the charity fund, the girl is prioritized. This is because “it is the way” (דרכו) for a man to seek charity publicly, whereas it is not for women (making her need greater).

תנו רבנן:

יתום ויתומה שבאו להתפרנס —

מפרנסין את היתומה, ואחר כך מפרנסין את היתום,

מפני שהאיש דרכו לחזור על הפתחים, ואין אשה דרכה לחזור.

The Sages taught:

Concerning an orphan boy and an orphan girl who have come and appealed to be supported by the charity fund,

the distributors provide for the orphan girl first and afterward they provide for the orphan boy.

This is because it is the way of a man to circulate about the entryways to ask for charity, and it is not a woman’s way to circulate for charity. Therefore, her need is greater.

ספר הזכרונות דברי הימים - literally: “the ‘book of remembrances’ [of] the ‘words of the days’ “.

The biblical phrase is intriguing because it combines two terms for documentation:

ספר הזכרונות – “The book of remembrances”

דברי הימים – “The words of the days”

Both elements suggest a form of historical record-keeping, but they have slightly different nuances:

ספר הזכרונות (Sefer HaZikhronot): This term implies a commemorative document, a record meant to preserve and recall past events. The root ז-כ-ר (z-k-r) means "to remember”, so Sefer HaZikhronot literally means “Book of Memories (זכרונות)”, suggesting that this book serves as a way to ensure important acts are not forgotten. It parallels the idea of memorial inscriptions and records of significant deeds, especially those deserving of reward or punishment.

דברי הימים (Divrei HaYamim): This term is more of a chronicle, a sequential log of events as they occurred, much like a court annal. The phrase divrei hayamim appears frequently in biblical literature to refer to royal chronicles (e.g., I Kings 14:19, 14:29) and is also the title of the biblical books Chronicles (Divrei HaYamim I & II). It emphasizes not just memory but recording daily events in a formal manner.

נקראים - a passive construction. See my piece “Answering Questions with Questions: On The Frequent Use of Rhetorical Questions in the Talmud” regarding Talmudic linguistic style, that as part of the broader scarcity of abstract language, passive constructions are also rare in Talmudic Hebrew. This explains why the Talmud perceives the passive form as unusual.

Stating: “There are several men named Mordecai among the Jews“ ( טובא מרדכי איכא ביהודאי).

See a similar trope in the talmudic story of the amora Shmuel and the Orphans’ Money, section “Part 2: Conversations in the Afterlife, looking for his father“, where I write:

“At the cemetery, in an ascent to the afterlife, Shmuel speaks to various spirits, looking for his father”:

אמר להו:

בעינא “אבא”!

אמרו ליה: “אבא” טובא איכא הכא.

!אמר להו: בעינא “אבא בר אבא”!

אמרו ליה: “אבא בר אבא” נמי טובא איכא הכא.

אמר להו: בעינא “אבא בר אבא, אבוה דשמואל”! היכא?

אמרו ליה: סליק למתיבתא דרקיעא.

and said to the dead:

I want “Abba”!

The dead said to him: There are many “Abbas” here.

He told them: I want “Abba bar Abba”!

They said to him: There are also many people named “Abba bar Abba” here.

He told them: I want “Abba bar Abba, the father of Shmuel”! Where is he?

They replied: Ascend to the Heavenly Yeshiva (מתיבתא דרקיעא).

This trope—where a character asks for a person by name and receives the response that many people share that name, requiring further specification—appears multiple times in Talmudic literature. It serves several functions, both narrative and rhetorical:

Comedic or Playful Delay

The trope introduces a brief moment of humorous or dramatic tension. The speaker expects an immediate answer but instead faces an absurd obstacle: an overabundance of individuals with the same name. In the case of Haman, this likely to be read as a comedic evasion tactic, buying time or feigning confusion to avoid carrying out the king’s command. (Compare the midrashic story of Laban giving his daughter to Jacob.)

Establishing Precision in Identity

In both stories, the repetition emphasizes the need for clear identification. This reflects a general rabbinic concern with specificity—names alone are not always sufficient to pinpoint an individual. This mirrors halakhic and legal principles where precision in testimony, transactions, and lineage is crucial.

Critique of Bureaucratic or Cosmic Order

The trope can also be read as a critique of systems that fail to distinguish between individuals. In the Haman story, it highlights how the king’s edict must be made explicit, as bureaucratic confusion could lead to unintended consequences. (Compare the Talmudic story of the Angel of Death’s messenger taking the life of the wrong Miriam.)

In the Shmuel story, it underscores the idea that in the afterlife, souls are not instantly known—Shmuel must navigate this system to reach his father.

Thematic Parallels: Earthly vs. Heavenly Confusion

In the case of Haman, the confusion occurs in an earthly court, where names serve as markers of legal and social identity. The trope adds to the irony of Haman’s situation, as he scrambles to find a way out of honoring Mordecai.

In Shmuel’s case, the confusion happens in the afterlife, showing a parallel cosmic structure: even in the world of the dead, specificity matters, and the search for truth requires persistence.

Rhetorical Amplification

The repetition of questions and incremental refinement of answers is a known rhetorical device in rabbinic storytelling. It serves to engage the listener, create suspense, and drive home a point through iteration.