A Quantitative Analysis of the Talmudic ‘Sugya’: Identifying the Upper Bound of Sugya Length, and Lower Bound of Number of Sugyot

Definition of ‘Sugya’

A sugya (plural: sugyot) represents a unit of Talmudic discourse.1

See Wikipedia, “Gemara”, section “The Sugya”:

The building block of gemara is known as a sugya, "a self-contained basic unit of Talmudic discussion" [...] that often centers on a statement from the mishnah, the amoraic rabbis (memra), or simply independent of these.

And see Wikipedia, “Sugya”:

A sugya is a self-contained passage of the Talmud that typically discusses a mishnah or other rabbinic statement, or offers an aggadic narrative [...]

While the sugya is a literary unit in the Jerusalem Talmud, the term is most often used for passages in the Babylonian Talmud, which is the primary focus of religious and academic readings of sugyot (plural form).

Religious and academic scholars of Talmud have identified numerous sugyot, though there is no definitive listing or count. Individual sugyot have been explained for readers, taught as curricular units, and analyzed by historians and other scholars.

Our working definition of ‘sugya’, in this piece: “the Talmudic text that occurs between consecutive mishnah sections”

For the purposes of this piece, we’ll be defining ‘sugya’ as the Talmudic text that occurs between consecutive mishnah sections. This is the upper bound of a sugya.2

This analysis examines a comprehensive dataset mapping every mishnah citation in Talmud Bavli to its precise location on the page, allowing for the calculation of sugya lengths based on the textual space between consecutive mishnayot.3

Outline

Definition of ‘Sugya’

Our working definition of ‘sugya’, in this piece: “the Talmudic text that occurs between consecutive mishnah sections”

Methodology

Results

The Longest Sugya

Top Ten Longest sugyot

Distribution Patterns

Limitations and Future Research

Conclusion

Appendix 1 - Ed. Steinsaltz’s splitting into sugyot, vs. my initial Outline/Table of Contents

Appendix 2 - Where on the page does each Chapter start?

Appendix 3 - Talmudic Indexes: Existing Talmudic Indexes, and Index vs. Outline, and Towards an Outline of Select Chapters and Sugyot

Outlines

My outline of Sanhedrin chapter 10 (Perek Chelek), including keywords per segment

Appendix 4 - Table of longest sugyot by number of folios (=’dapim’)

Methodology

The analysis used a CSV dataset (at Sefaria github) containing 2,390 entries mapping mishnah sections to their locations in Talmud Bavli.4 Each entry specified the tractate, chapter, mishnah range, starting page5 and line, and ending page and line.

To calculate sugya lengths, we measured the textual distance between the end of one mishnah citation and the beginning of the next within each tractate. The calculation converted traditional page notation (e.g., "71a", "94b") into numerical positions, accounting for both page numbers and sides (a/b).6

Data processing involved grouping entries by tractate and sorting them by chapter and mishnah number to ensure proper sequential ordering. Only positive-length sugyot were included in the final analysis, filtering out cases where end-of-tractate entries produced negative values.7

Results

The analysis identified 2,348 distinct sugyot8 across Talmud Bavli.

The Longest Sugya

The longest continuous Talmudic discussion occurs in Tractate Menachot, spanning from the end of Mishnah 10:8-9 to the beginning of Mishnah 11:1. This sugya extends from daf 71a:9 to 94a:11, covering approximately 692 lines of Talmud text—equivalent to roughly 23 daf pages of discussion.

In many cases, the long sugya is partially an artefact of the fact that all the Mishnayot of the chapter are placed at the beginning of the chapter, instead of spread out throughout the chapter. (See for example Sanhedrin Chapter 1; Berakhot Chapter 9.)

Top Ten Longest sugyot

Menachot 10:8-9 → 11:1: 23 folios [=dapim] (71a:9 → 94a:11)

Sanhedrin 10:1-2 → 10:3: 18 folios (90a:17 → 107b:18)9

Sanhedrin 1:6 → 2:1-2: 16 folios (2b:2 → 18a:5)

Rosh Hashanah 1:1 → 1:2: 14 folios (2a:4 → 16a:1)

Pesachim 10:1 → 10:2: 15 folios (99b:1 → 114a:4)10

Bava Batra 3:3 → 3:4: 14 folios (42a:9 → 56a:10)11

Kiddushin 1:1 → 1:2: 12 folios (2a:2 → 14b:2)12

Shevuot 1:7 → 2:1: 12 folios (2b:11 → 14a:12)13

Bava Batra 3:1 → 3:2: 10 folios (28a:5 → 38a:4)

Chullin 3:1 → 3:2: 12 folios (42a:5 → 54a:13)14

Miscellaneous manual counts of end-of-tractate sugyot:

Berakhot 9:5 → end of tractate: 10 folios (Berakhot 54a:10 → Berakhot 64a:14)15

Sanhedrin 10:6 → end of tractate: 2 folios (Sanhedrin 111b:10 → Sanhedrin 113b:3)16

Bava Kamma 10:10 → end of tractate: 1 folio (Bava Kamma 119a:24 → Bava Kamma 119b:20)

Distribution Patterns

The length distribution reveals that most sugyot are relatively brief. However, certain topics generated extensive deliberation, or go on extensive tangents, resulting in discussions that span multiple pages.

Notably, several of the longest sugyot occur at the beginning of tractates or major sections, suggesting that foundational concepts often required more elaborate explanation and debate, or engender extensive tangents.

Limitations and Future Research

This analysis relied on estimated line counts based on page structure. More precise measurements would require character or word counts of the actual text. Additionally, the analysis focused purely on quantitative length without considering the content.

Future research could examine the relationship between sugya length and topic complexity and tangents, analyze the distribution of long sugyot across different historical periods reflected in the text, or investigate whether certain types of legal or theological questions systematically generate longer discussions.

The methodology developed here could also be applied to other Talmudic corpora, such as the Jerusalem Talmud, to enable comparative analysis of discourse patterns across different rabbinical traditions.

Conclusion

This analysis successfully identified the longest continuous Talmudic discussions in Bavli, revealing significant variation in the extent of rabbinical elaboration across different topics. The Menachot sugya spanning 692 lines represents the most extensive single discussion, while the overall pattern of long sugyot reflects the complexity of topics central to Jewish law and practice. These findings provide a quantitative foundation for understanding the structure and emphasis of Talmudic discourse.

Appendix 1 - Ed. Steinsaltz’s splitting into sugyot, vs. my initial Outline/Table of Contents

Ed. Steinsaltz marks the beginning of a new ‘sugya’ with a section symbol (‘§’).

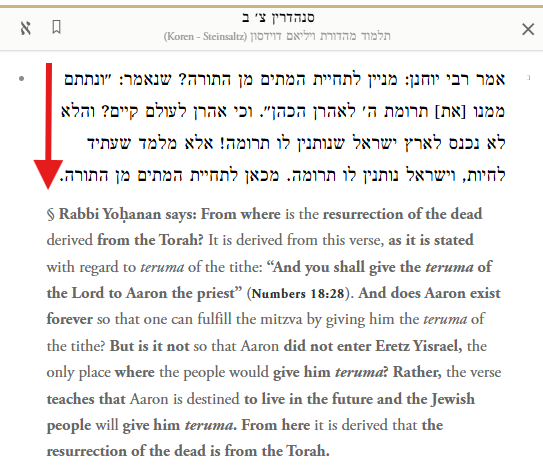

For example, at Sanhedrin.90b.2:

I found at Sefaria’s github repo that they seem to list this in a CSV, by tractate.

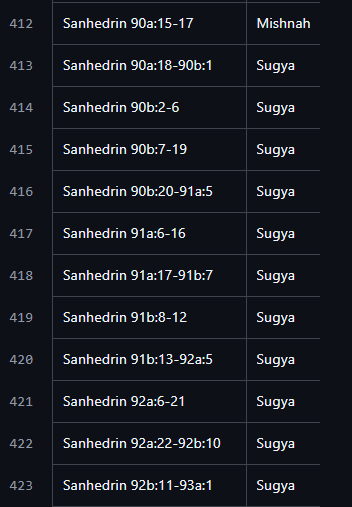

For example, for tractate Sanhedrin, beginning of Chapter 10 (Perek Chelek):

https://github.com/Sefaria/Sefaria-Project/blob/master/data/sugyot/Sanhedrin.csv

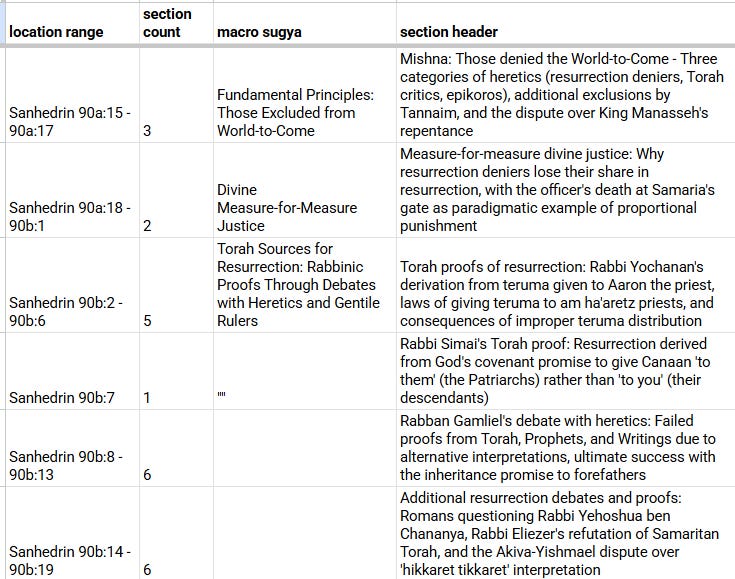

Compare this with my initial outline/table of contents:17

Appendix 2 - Where on the page does each Chapter start?

As part of developing ChavrutAI, this question came up: Where exactly on the page does each Chapter start? Meaning, which section of the page, in the ed. Steinsaltz? I had the epiphany that this CSV database, as a happy additional benefit, answers this question. I simply filtered for ‘Start Mishnah’ = 1.

For example, for tractate Zevachim, Zevachim Chapter 2 starts at Zevachim 15b:9 (=folio 15, side B, section 15):

Appendix 3 - Talmudic Indexes: Existing Talmudic Indexes, and Index vs. Outline, and Towards an Outline of Select Chapters and Sugyot

See Wikipedia, “Index (publishing)”:

An index (pl.: usually indexes, more rarely indices) is a list of words or phrases ('headings') and associated pointers ('locators') to where useful material relating to that heading can be found in a document or collection of documents.

Examples are an index in the back matter of a book and an index that serves as a library catalog.

An index differs from a word index, or concordance, in focusing on the subject of the text rather than the exact words in a text, and it differs from a table of contents because the index is ordered by subject, regardless of whether it is early or late in the book, while the listed items in a table of contents is placed in the same order as the book.

In a traditional back-of-the-book index, the headings will include names of people, places, events, and concepts selected as being relevant and of interest to a possible reader of the book.

The indexer performing the selection may be the author, the editor, or a professional indexer working as a third party.

The pointers are typically page numbers, paragraph numbers or section numbers.

To reiterate: “An index [....] differs from a table of contents because the index is ordered by subject, regardless of whether it is early or late in the book, while the listed items in a table of contents is placed in the same order as the book.”

An index is (relatively speaking) more straightforward to create than an outline. For example, it doesn’t run into the issue of delineating sections of discourse (sugyot), and it can be minimal and sparse.

Examples of existing Talmud indices:18

A volume in 20th century ed. Soncino translation of Talmud19

Mordechai Torczyner's WebShas - Topical Index to the Talmud: English Index

Daniel Retter, HaMafteach (Koren / Feldheim, 2011)20

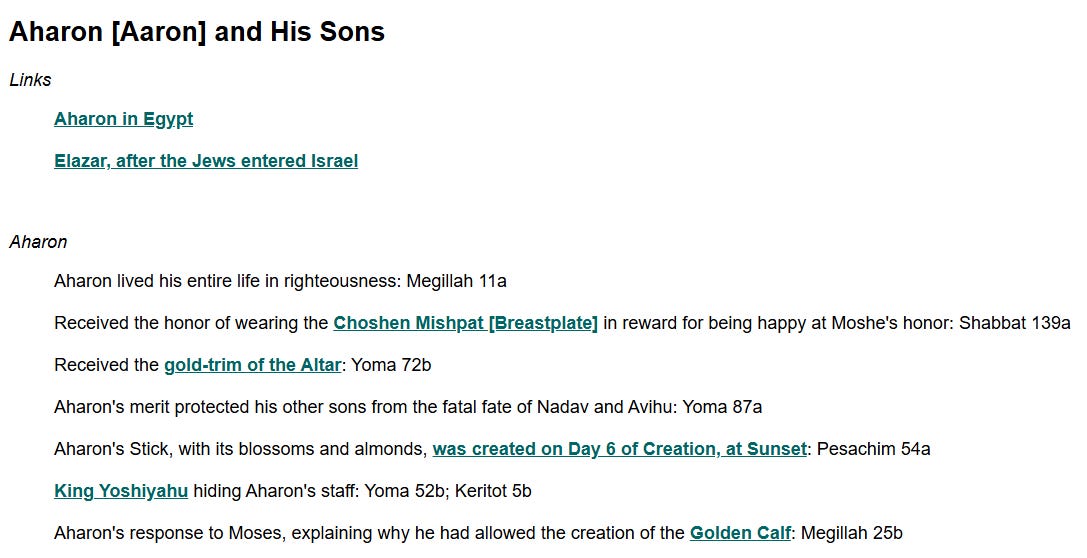

Example index entry from Torczyner's index, ibid., “Aharon”, link and screenshot of first rows:

https://www.webshas.org/torah/bichtav/tanach/midbar/aharon.htm

Outlines

Compare outlines of classical works, i.e. modern outlines of Bible and of Greco-Roman works.

Examples:

Bible study guides such as those for the Book of Joshua (by Christians: biblestudystart.com; biblesummary.info) offer simplified structures designed for devotional or teaching use.

A concise outline of the Aeneid and other epics, at Duke University website (link),

An extensive outline of Plato’s Republic (link).

My outline of Sanhedrin chapter 10 (Perek Chelek), including keywords per segment

I recently uploaded it to my Academia page: “Outline of Talmud Bavli Sanhedrin Chapter 10 (Perek Chelek)”.

Technical:

I set up a Claude AI project

I exported Steinsaltz brachot from Sefaria, as Excel file

I fine-tuned a prompt to Claude (model: 4.0, "thinking"):

then, converted JSON to table/Excel format, and appended to my main table

I created a separate fine-tuned prompt for Claude AI, for keyword extraction, and appended the output to the main table (these keywords are roughly equivalent to index entries, see earlier on index entries in general)

Additional extensive post-processing

Appendix 4 - Table of longest sugyot by number of folios (=’dapim’)

Sometimes discrete, sometimes not, see further.

See discussion in the recent book by Rosen-Zvi and Meir, ‘Talmud’.

For attempts to split into sugyot by topic, see for example the ones at “Talmud HaIgud”, within each chapter; and see Katz’s “Mahberet Menahmiyot”.

Because the Talmud unfolds through associative links rather than strict boundaries, breaking it into discrete sugyot is often somewhat artificial.

As an aside, somewhat related to this, I’m working on developing an outline/table of contents of the Talmud, by content. As part of my ongoing ChavrutAI web app development.

See more on this in an appendix at the end of this piece: “Appendix 3 - Talmudic Indexes: Existing Talmudic Indexes, and Index vs. Outline, and Towards an Outline of Select Chapters and Sugyot“.

I discovered this dataset via the following Mi Yodeya forum post, from 2015: “Where are the Mishnas in the Talmud?”; see Laizer’s response there.

As I’ve noted a number of times, “page” in the context of Talmud refers to the traditional pagination of the printed Talmud, starting with the 16th-century Bomberg Venice edition. The page is daf (=folio) + a/b (=recto/verso).

For other pieces of mine related to this topic, see for example:

The calculation of length is based on folio (=dapim); I did this manually. The calculation is very rough, and is a very rough heuristic.

In this regard, it is important to note that end-of-tractate sugyot were not fully counted, due to limitations of the data in the CSV database. However, I counted some of those manually, see later.

Which is thus the lower bound of the number of sugyot in the Talmud; as mentioned in the intro, what we’re defining as a sugya (Talmud text from one Mishnah section to the next) is in fact generally broken up into multiple sugyot.

Note: Sanhedrin Chapter 10 (Perek Chelek) is the second-longest chapter in the Talmud, by word count, see my other piece. It contains extensive aggadic discussions.

Note: Pesachim 10 contains extensive aggadic discussions; see all my pieces on it.

Note: Bava Batra Chapter 3 contains extensive aggadic discussions, see my recent three-part series.

In addition, Rashbam’s relatively verbose commentary leads to a greater number of pages.

Note: Kiddushin Chapter 1 is the longest chapter in the Talmud, by word count, see my other piece.

Note: Ran’s relatively verbose commentary leads to a greater number of pages.

Note: Chullin Chapter 3 is one of the longest chapters in the Talmud.

Note: Berakhot Chapter 9 is one of the longest chapters in the Talmud.

Note: unusually, Sanhedrin Chapter 10 is presented after Sanhedrin Chapter 11 in the traditional print and pagination.

Using AI, specifically Anthropic’s Claude, in a project, with advanced fine-tuning via a very detailed, fine-tuned prompt. See my discussion later.

Thanks to members of the ‘Ask the Beit Midrash’ Facebook page for a recent discussion of this, in response to my question there.

See at the NLI index here: “Accompanied by index volume compiled by Judah Slotki, with a foreword by Israel Brodie, published 1952.”

And see an image of the spine of the volume at the Amazon listing page.

JTS is into this in their doctoral programs. There are several people there that qualify as ‘Gedolim’. However, because of their affiliation, we ‘must be dismissive’.

They are there because of the facilities. Their library is unique and impressive.