‘And it Came to Pass’: The Ominous Implication of “Va-Yehi” in Biblical Narratives (Megillah 10b)

The Bible’s narrative power often lies not only in what it says, but in how it says it. Ancient interpreters, attuned to the resonances of language and repetition, found deep significance in even the most formulaic turns of phrase.

One such phrase—“וַיְהִי” (vayhi, “and it came to pass”, a frequently used narrative connector in biblical stories)1—has long invited midrashic scrutiny. In a tradition preserved in the Talmud, attributed to R’ Levi or possibly R’ Yonatan and transmitted from the “Men of the Great Assembly” (אנשי כנסת הגדולה), this otherwise innocuous narrative marker is imbued with ominous portent: Wherever “vayhi” appears, they suggest, sorrow is soon to follow.2

This tradition is introduced in connection with the opening of the Book of Esther—“And it came to pass in the days of Ahasuerus”—a verse that, the rabbis argue, heralds not the festive reversal for which Esther is best known, but the ascent of Haman and the threat of Jewish annihilation.3

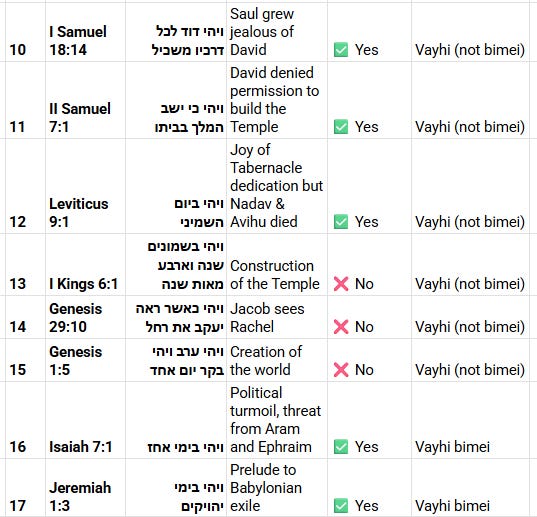

From here, the Talmud embarks on an aggadic exploration of biblical precedent, compiling a catalog of verses in which the word vayhi introduces calamity, strife, or sorrow—from the generation of the Flood to the war of the kings in Genesis, from famine in Ruth to the rebellion of Israel under Joshua.

Yet, as often in rabbinic dialectic, the rule invites challenge. What of the Tabernacle’s joyous dedication? Or the patriarch Jacob’s first glimpse of Rachel? Or the repeated use of vayhi in the narrative of Creation itself? The Talmud responds with nuance, sometimes reaffirming the association of vayhi with grief by uncovering hidden tragedy—such as the death of Nadav and Avihu on the very day of the Tabernacle’s dedication—and at other times acknowledging that the rule does not hold universally.

Ultimately, Rav Ashi offers a refinement: while “vayhi” may occasionally accompany joy, the more specific formulation “vayhi bi-mei” (“and it came to pass in the days of”) is consistently linked with distress. The Talmud identifies the five biblical occurrences of this phrase, each followed by a historical or moral crisis.

Outline

Intro

The Passage - ‘And it Came to Pass’: The Ominous Implication of “Va-Yehi” in Biblical Narratives (Megillah 10b)

R’ Levi / R’ Yonatan transmits a tradition from the Men of the Great Assembly - Grief Associated with “Vayhi” (Esther 1:1)

List of Eleven Negative Outcomes Introduced by “Vayhi” (ויהי) Verses

Reconsidering the Association of “Vayhi” with Grief: Challenge from the Tabernacle’s Dedication (Leviticus 9:1; Genesis 1:5); Rebuttal: Death of Nadav and Avihu;

Further Counterexamples to the Rule; Conclusion: The Rule Does Not Hold Universally

Rav Ashi - The Phrase “Vayhi Bimei” as a Biblical Omen of Grief: Dual Meaning of “Vayhi”, Grief Associated with “Vayhi Bimei”

Five biblical appearances of “vayhi bimei”, each followed by tragic or troubling events

Appendix 1 - Summary Table of the Analysis of “Vayhi” and “Vayhi Bimei” as Portents of Sorrow

Appendix 2 - Additional Traditions of R’ Levi: Lineage, Modesty, and Miracles in Genesis 38, Isaiah 1 and I Kings 6 (Megillah 10b)

Amoz and Amaziah Were Brothers

Modesty and Lineage: Tamar as the Ancestress of Kings and Prophets (Genesis 38:15; Isaiah 1:1): Modesty as a Merit for Great Descendants; Tamar as the Exemplary Case; The Resulting Royal Lineage; Prophetic Descent

The Miraculous Non-Dimensionality of the Ark in the Holy of Holies (I Kings 6:20): Ancestral Tradition on the Ark’s Placement; Contradiction in Cherub Dimensions

The Passage

R’ Levi / R’ Yonatan transmits a tradition from the Men of the Great Assembly - Grief Associated with “Vayhi” (Esther 1:1)

R’ Levi, or possibly R’ Yonatan, transmits a tradition from the Men of the Great Assembly:

Whenever the Bible opens with the word “vayhi” (וַיְהִי, “and it came to pass”), it signals impending sorrow (צער ).

״ויהי בימי אחשורוש״,

אמר רבי לוי,

ואיתימא רבי יונתן:

דבר זה מסורת בידינו מאנשי כנסת הגדולה:

כל מקום שנאמר ״ויהי״,

אינו אלא לשון צער.

The opening verse of the Megilla states: “And it came to pass [vayhi] in the days of Ahasuerus” (Esther 1:1).

R’ Levi said,

and some say that it was R’ Yonatan who said:

This matter is a tradition that we received from the members of the Great Assembly.

Anywhere that the word vayhi is stated,

it is an ominous term indicating nothing other than impending grief,

as if the word were a contraction of the words vai and hi, meaning woe and mourning.

List of Eleven Negative Outcomes Introduced by “Vayhi” (ויהי) Verses

Multiple verses are adduced to support this grim pattern:4

Esther 1:1 - Followed by the rise of Haman and threat to Jews

Ruth 1:1– Followed by the famine during the judges’ rule.

Genesis 6:1 - “The wickedness of man was great”

Genesis 11:2 - Tower of Babel

Genesis 14:1– Outbreak of War of Kings

Joshua 5:13 - Angel with drawn sword

Joshua 6:27 – Sin of Achan

I Samuel 1:1 - Hannah’s barrenness

I Samuel 8:1 – Samuel’s Corrupt Sons

I Samuel 18:14 – Saul’s Jealousy of David

II Samuel 7:1 - David denied permission to build the Temple

״ויהי בימי אחשורוש״ —

הוה המן.

״ויהי בימי שפוט השופטים״ —

הוה רעב.

״ויהי כי החל האדם לרוב״ —

״וירא ה׳ כי רבה רעת האדם״.

״ויהי בנסעם מקדם״ —

״הבה נבנה לנו עיר״.

״ויהי בימי אמרפל״ —

״עשו מלחמה״.

״ויהי בהיות יהושע ביריחו״ —

״וחרבו שלופה בידו״.

״ויהי ה׳ את יהושע״ —

״וימעלו בני ישראל״.

״ויהי איש אחד מן הרמתים״ —

״כי את חנה אהב, וה׳ סגר רחמה״.

״ויהי (כי) זקן שמואל״ —

״ולא הלכו בניו בדרכיו״.

״ויהי דוד לכל דרכיו משכיל [וה׳ עמו]״ —

״ויהי שאול עוין את דוד״.

״ויהי כי ישב המלך בביתו״ —

״רק אתה לא תבנה הבית״.

The Talmud cites several proofs corroborating this interpretation.

“And it came to pass [vayhi] in the days of Ahasuerus”

led to grief, as there was Haman.

“And it came to pass [vayhi] in the days when the judges ruled” (Ruth 1:1)

introduces a period when there was famine.

“And it came to pass [vayhi], when men began to multiply” (Genesis 6:1)

is immediately followed by the verse: “And YHWH saw that the wickedness of man was great in the earth” (Genesis 6:5).

“And it came to pass [vayhi] as they journeyed from the east” (Genesis 11:2)

is followed by: “Come, let us build us a city” (Genesis 11:4), which led to the sin of the Tower of Babel.

“And it came to pass in the days of Amraphel” (Genesis 14:1),

about whom it is stated: “These made war” (Genesis 14:2).

“And it came to pass, when Joshua was by Jericho” (Joshua 5:13),

it was there that he saw an angel “with his sword drawn in his hand” as a warning.

“And YHWH was [vayhi] with Joshua” (Joshua 6:27),

and immediately afterward: “But the children of Israel committed a trespass” (Joshua 7:1).

“And it came to pass that there was a certain man of Ramathaim” (I Samuel 1:1),

and it mentions shortly afterward Hannah’s inability to conceive: “For he loved Hannah, but YHWH had closed up her womb” (I Samuel 1:5).

“And it came to pass, when Samuel was old” (I Samuel 8:1),

and then it is written: “And his sons did not walk in his ways” (I Samuel 8:3).

“And it came to pass that David was successful in all his ways, and YHWH was with him” (I Samuel 18:14),

and only a few verses prior it is written: “And Saul viewed David with suspicion” (I Samuel 18:9).

“And it came to pass, when the king dwelt in his house” (II Samuel 7:1).

Here King David mentioned his desire to build a temple for God, but it is written elsewhere that he was told:

“Yet you shall not build the house” (II Chronicles 6:9).

Reconsidering the Association of “Vayhi” with Grief: Challenge from the Tabernacle’s Dedication (Leviticus 9:1; Genesis 1:5); Rebuttal: Death of Nadav and Avihu

The Talmud questions this principle by pointing to “vayhi” in the context of the joyous dedication of the Tabernacle.

A baraita even compares the day’s joy to that of Creation, connecting vayhi in Leviticus 9:1 with vayhi in Genesis 1:5 via a verbal analogy.

The Talmud defends the original principle by recalling that Nadav and Avihu died that same day (thus introducing grief into what seemed like a purely joyful occasion).

והכתיב: ״ויהי ביום השמיני״,

ותניא:

אותו היום היתה שמחה לפני הקדוש ברוך הוא

כיום שנבראו בו שמים וארץ,

כתיב הכא:

״ויהי ביום השמיני״,

וכתיב התם:

״ויהי (בקר) יום אחד״

הא שכיב נדב ואביהוא.

After citing several verses where vayhi portends grief, the Talmud mentions a number of verses that seem to indicate otherwise.

But isn’t it written: “And it came to pass [vayhi] on the eighth day” (Leviticus 9:1), which was the day of the dedication of the Tabernacle?

And it is taught in a baraita with regard to that day:

On that day there was joy before God,

similar to the joy that existed on the day on which the heavens and earth were created.

The Talmud cites a verbal analogy in support of this statement.

It is written here, with regard to the dedication of the Tabernacle:

“And it came to pass [vayhi] on the eighth day,”

and it is written there, in the Creation story:

“And it was [vayhi] evening, and it was morning, one day” (Genesis 1:5).

This indicates that there was joy on the eighth day, when the Tabernacle was dedicated, similar to the joy that existed on the day the world was created. Apparently, the term vayhi is not necessarily a portent of grief.

The Talmud answers: This verse does not contradict the principle. On the day of the dedication of the Tabernacle, a calamity also befell the people, as Nadav and Avihu died.

Further Counterexamples to the Rule; Conclusion: The Rule Does Not Hold Universally

Additional verses are cited where vayhi does not herald grief:

The 480th year marking the Temple’s construction (I Kings 6:1)

Jacob’s first sighting of Rachel (Genesis 29:10)

Multiple days in the Creation narrative (Genesis 1:5 and onward)

(Given these exceptions, the Talmud concludes that vayhi does in fact not inherently signal grief, challenging the original assumption.)

והכתיב: ״ויהי בשמונים שנה וארבע מאות שנה״

והכתיב: ״ויהי כאשר ראה יעקב את רחל״

והכתיב: ״ויהי ערב ויהי בקר יום אחד״

והאיכא שני

והאיכא שלישי

והאיכא טובא

The Talmud cites additional verses where vayhi is not indicative of impending grief:

But isn’t it written: “And it came to pass [vayhi] in the 480th year” (I Kings 6:1), which discusses the joyous occasion of the building of the Temple?

And furthermore, isn’t it written: “And it came to pass [vayhi] when Jacob saw Rachel” (Genesis 29:10), which was a momentous occasion?

And isn’t it written: “And it was [vayhi] evening, and it was [vayhi] morning, one day” (Genesis 1:5)?

And isn’t there the second day of Creation,

and isn’t there the third day, where the term vayhi is used?

And aren’t there many verses in the Bible in which the term vayhi appears and no grief ensues?

Apparently, the proposed principle is incorrect.

Rav Ashi - The Phrase “Vayhi Bimei” as a Biblical Omen of Grief: Dual Meaning of “Vayhi”, Grief Associated with “Vayhi Bimei”

Rav Ashi distinguishes between the general word vayhi (“and it came to pass”), which can indicate either joy or grief, and the more specific phrase vayhi bimei (ויהי בימי - “and it came to pass in the days of”), which consistently foreshadows sorrow.

אמר רב אשי:

כל ״ויהי״ —

איכא הכי, ואיכא הכי,

״ויהי בימי״ —

אינו אלא לשון צער

Rather, Rav Ashi said:

With regard to every instance of vayhi alone —

there are some that mean this, grief, and there are some that mean that, joy.

However, wherever the phrase “and it came to pass in the days of [vayhi bimei]” is used in the Bible —

it is nothing other than a term of impending grief.

Five biblical appearances of “vayhi bimei”, each followed by tragic or troubling events

The Talmud lists the five biblical appearances of vayhi bimei, each followed by tragic or troubling events:5

Esther 1:1 - the reign of Ahasuerus (mentioned earlier; Rise of Haman and threat to Jews)

Ruth 1:1 - the era of the Judges (mentioned earlier; Famine in the land)

Genesis 14:1 - the time of Amraphel (mentioned earlier; Outbreak of war of kings)

Isaiah 7:1 - the rule of Ahaz

Jeremiah 1:3 - the days of Jehoiakim (Prelude to Babylonian exile)

חמשה ״ויהי בימי״ הוו:

״ויהי בימי אחשורוש״,

״ויהי בימי שפוט השופטים״,

״ויהי בימי אמרפל״,

״ויהי בימי אחז״,

״ויהי בימי יהויקים״.

The Talmud states that there are five instances of vayhi bimei in the Bible:

“And it came to pass in the days of [vayhi bimei] Ahasuerus”;

“And it came to pass in the days [vayhi bimei] when the judges ruled”;

“And it came to pass in the days of [vayhi bimei] Amraphel”;

“And it came to pass in the days of [vayhi bimei] Ahaz” (Isaiah 7:1);

“And it came to pass in the days of [vayhi bimei] Jehoiakim” (Jeremiah 1:3).

In all those incidents, grief ensued.

Appendix 1 - Summary Table of the Analysis of “Vayhi” and “Vayhi Bimei” as Portents of Sorrow

Appendix 2 - Additional Traditions of R’ Levi: Lineage, Modesty, and Miracles in Genesis 38, Isaiah 1 and I Kings 6 (Megillah 10b)

Amoz and Amaziah Were Brothers

R’ Levi transmits a tradition that Amoz, father of the prophet Isaiah, and Amaziah, king of Judea, were brothers.

ואמר רבי לוי:

דבר זה מסורת בידינו מאבותינו:

אמוץ ואמציה — אחי הוו

[...]

Apropos the tradition cited by R’ Levi above, the Talmud cites additional traditions that he transmitted.

R’ Levi said:

This matter is a tradition that we received from our ancestors:

Amoz, father of Isaiah, and Amaziah, king of Judea, were brothers.

[...]

Modesty and Lineage: Tamar as the Ancestress of Kings and Prophets (Genesis 38:15; Isaiah 1:1): Modesty as a Merit for Great Descendants; Tamar as the Exemplary Case; The Resulting Royal Lineage; Prophetic Descent

R’ Shmuel bar Naḥmani states in the name of R’ Yonatan that a bride who is modest (צנועה) in her father-in-law’s house merits descendants who are kings and prophets.

אמר רבי שמואל בר נחמני, אמר רבי יונתן:

כל כלה שהיא צנועה בבית חמיה —

זוכה ויוצאין ממנה מלכים ונביאים.

R’ Shmuel bar Naḥmani said that R’ Yonatan said:

Any bride who is modest in the house of her father-in-law —

merits that kings and prophets will emerge from her.

This teaching is derived from the case of Tamar:

When Judah mistook her for a prostitute because she had covered her face (Genesis 38:15), the Talmud clarifies this was not due to immodesty but because she had been modest earlier, covering her face in her father-in-law’s house such that Judah did not recognize her.

As a result of her modesty, Tamar became the ancestress of kings.

מנלן?

מתמר,

דכתיב:

״ויראה יהודה

ויחשבה לזונה

כי כסתה פניה״,

משום דכסתה פניה,״ויחשבה לזונה״?!

אלא

משום דכסתה פניה בבית חמיה,

ולא הוה ידע לה,

זכתה ויצאו ממנה מלכים ונביאים.

From where do we derive this?

From Tamar, as it is written:

“When Judah saw her,

he thought her to be a prostitute;

for she had covered her face” (Genesis 38:15).

Can it be that because Tamar covered her face he thought her to be a prostitute?! On the contrary, a harlot tends to uncover her face.

Rather,

because she covered her face in the house of her father-in-law

and he was not familiar with her appearance, Judah didn’t recognize Tamar, thought she was a harlot, and sought to have sexual relations with her.

Ultimately, she merited that kings and prophets emerged from her.

As a result of her modesty, Tamar became the ancestress of kings, i.e. David, through her son Peretz.

Though the prophetic lineage is not explicit, the Talmud cites the tradition (quoted in the previous section) that Amoz, father of the prophet Isaiah, was the brother of King Amaziah (thereby placing Isaiah within the Davidic line and thus also descended from Tamar).

מלכים — מדוד,

נביאים —

דאמר רבי לוי:

מסורת בידינו מאבותינו:

אמוץ ואמציה אחים היו,

וכתיב: ״חזון ישעיהו בן אמוץ״.

Kings emerged from her through David, who was a descendant of Tamar’s son, Peretz.

However, there is no explicit mention that she was the forebear of prophets.

This is derived from that which R’ Levi said:

This matter is a tradition that we received from our ancestors:

Amoz, father of Isaiah, and Amaziah, king of Judea, were brothers,

and it is written: “The vision of Isaiah the son of Amoz” (Isaiah 1:1).

Amoz was a member of the Davidic dynasty, and his son, the prophet Isaiah, was also a descendant of Tamar.

The Miraculous Non-Dimensionality of the Ark in the Holy of Holies (I Kings 6:20): Ancestral Tradition on the Ark’s Placement; Contradiction in Cherub Dimensions

R’ Levi states a received tradition that the Ark of the Covenant (miraculously) did not occupy any measurable space within the Holy of Holies.

ואמר רבי לוי:

דבר זה מסורת בידינו מאבותינו:

מקום ארון אינו מן המדה.

And R’ Levi said:

This matter is a tradition that we received from our ancestors:

The place of the Ark of the Covenant is not included in the measurement of the Holy of Holies in which it rested.

A baraita confirms this idea, explaining that Moses’ Ark had 10 cubits of empty space on either side within a room 20 cubits wide, as described in I Kings 6:20.

The wings of the cherubs also spanned the entire 20 cubits, implying the Ark could not have physically fit between them.

The Talmud concludes that this all shows that indeed the Ark must have miraculously existed without taking up space (harmonizing the dimensions and affirming the tradition).

תניא נמי הכי:

ארון שעשה משה

יש לו עשר אמות לכל רוח,

וכתיב:

״ולפני הדביר

עשרים אמה אורך״,

וכתיב:

״כנף הכרוב האחד עשר אמות

וכנף הכרוב האחד עשר אמות״,

ארון גופיה היכא הוה קאי?

אלא לאו שמע מינה:

בנס היה עומד

The Talmud comments:

This is also taught in a baraita:

The Ark crafted by Moses had 10 cubits of empty space on each side.

And it is written in the description of Solomon’s Temple:

“And before the Sanctuary,

which was 20 cubits in length, and twenty cubits in breadth” (I Kings 6:20).

The place “before the Sanctuary” is referring to the Holy of Holies. It was 20 by 20 cubits. If there were 10 cubits of empty space on either side of the Ark, apparently the Ark itself occupied no space.

And it is written:

“And the wing of one of the cherubs was 10 cubits

and the wing of the other cherub was 10 cubits; the wings of the cherubs occupied the entire area.”

If so, where was the Ark itself standing?

Rather, must one not conclude from it that the Ark stood by means of a miracle and occupied no space?

This is traditionally explained as follows:

וַיְהִי - va-yehi = “And it came to pass”

Phonetically split:

“vai“ (וַי) – an interjection expressing woe or grief (like saying “Oh no!”)

“hi“ (הִי) – connected to mourning or lament, as part of a poetic/emotive tone

So, homiletically, the word וַיְהִי sounds like a merging of “woe” and “mourning”, leading to the idea that wherever “vayhi” appears, sorrow follows.

The ‘va-ye’ biblical prefix likely attracted Talmudic attention not simply due to its frequency, but because, viewed from a later linguistic standpoint, it relies on the archaic and conceptually puzzling ‘vav ha-hippuch’.

See Wikipedia, “Vav-consecutive“:

The vav-consecutive […] (וי״ו ההיפוך) is a grammatical construction in Canaanite languages, most notably in Biblical Hebrew.

It involves prefixing a verb form with the letter vav in order to change its tense or aspect.

And see ibid., section “Obsolescence“:

The Lachish letters, dating to c. 590 BCE, have only a single occurrence of vav-consecutive; in all other cases, the perfect form is used to describe events in the past.

This indicates that already in Late Biblical Hebrew the vav-consecutive was uncommon, especially outside of formal narrative style.

By the time of Mishnaic Hebrew, the vav-consecutive fell completely out of use […]

The vav consecutive is considered stereotypically biblical (analogous to “thus saith,” etc. in English) and is used jocularly for this reason by modern speakers, and sometimes in serious attempts to evoke a biblical context.

And see another similar Talmudic play on this biblical linguistic construct in my “The Temple’s Priestly and Non-Priestly Divisions: Their Formation, Function, and Revival From Moses to the Second Temple (Taanit 27a-b)“, section “Reish Lakish - ‘Va-Yinafash’: The Extra Soul of Shabbat - Exodus 31:17”.

This sugya appears at the beginning of the extended macro-sugya about the Book of Esther.

I analyzed that in a multiple part series; for all parts, see my index here, section “Megillah“.

The first part of that series is “Thematic Introductions to the Book of Esther in the Talmud (Megillah 10b-11a)“, final part here.

And see those all combined in my “Exile, Redemption, and the Hidden Hand of God: The Talmud’s Commentary on the Book of Esther in Megillah 10b-17a“, see my intro there.

That the formulaic opening “vayhi” precedes or signals a negative or troubling event in the upcoming narrative.