Counting the Letters in the Mishnah: Measuring the Length of All Four Thousand Individual Mishnayot (With analysis of Mishnah Yadayim 4:3)

In this project, I counted the number of characters (i.e. letters) in individual sections (Mishnayot) across all chapters of the Mishnah. Previously, I had focused on counting the words in entire chapters, but this time the emphasis was on measuring the length of each numbered Mishnah.1

For some reason, I found it more challenging to count words for this script, so I opted to count characters instead. The difference in results should be minimal.

Here’s the full table of character counts of all 4100 individual Mishnayot:

Analysis

It seems that the longest Mishnayot are those that feature either:

Relatively extensive back-and-forth halachic discussion. This is quite uncommon for the Mishnah, though much more typical in the anonymous sections of the Talmud.

Extended aggadic material. Again, rare for the Mishnah but common in both the Talmud and Midrash Aggadah.

I recently analyzed the longest Mishnah (Sotah 9:15), in two parts.2 That’s an example of #1: Extended aggadic material.

In this next section, I’ll analyze the second-to-longest Mishnah, which features #2: Extensive back-and-forth halachic discussion

Second to Longest Mishnah: Debating Tithes in the Seventh Year: Ammon and Moab's Obligation Settled by Tradition (Mishnah Yadayim 4:3)

The passage recounts a debate about the tithing obligations of residents of Ammon and Moab (territories east of the Jordan river, in present-day Jordan) during the seventh year (Shemittah). R' Tarfon ruled that these lands should give the tithe for the poor (מעשר עני), while R' Elazar ben Azariah decreed the second tithe (מעשר שני).

See Tithes in Judaism - Wikipedia:

The tithe is specifically mentioned in the Books of Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. The tithe system was organized in a seven-year cycle, the seventh-year corresponding to the Shemittah-cycle in which year tithes were broken-off, and in every third and sixth-year of this cycle the second tithe replaced with the poor man's tithe.

These tithes were akin to taxes for the people of Israel and were mandatory, not optional giving. This tithe was distributed locally "within thy gates" to support the Levites and assist the poor. Every year, Bikkurim, terumah, ma'aser rishon and terumat ma'aser were separated from the grain, wine and oil.

Initially, the commandment to separate tithes from one's produce only applied when the entire nation of Israel had settled in the Land of Israel. The Returnees from the Babylonian exile who had resettled the country were a Jewish minority, and who, although they were not obligated to tithe their produce, put themselves under a voluntary bind to do so, and which practice became obligatory upon all.

Outline

The Question and Initial Positions

Who has the burden of proof?

R' Yishmael

R' Elazar ben Azariah

Geographical Comparison Arguments: Is Ammon and Moab more analogous to Egypt, or to Babylonia?

R' Tarfon

R' Elazar ben Azariah (Malakhi 3:8)

R' Yehoshua's Intervention Re Precedent

New vs. Old

Elders vs. Prophets

Final Resolution and Validation

The Passage

The Question and Initial Positions

See my intro for explanation of this section.

בו ביום אמרו:

עמון ומואב, מה הן בשביעית?

גזר רבי טרפון -- מעשר עני.

וגזר רבי אלעזר בן עזריה -- מעשר שני.

On that day3 they said:

what is the law applying to Ammon and Moab in the seventh year?

R' Tarfon — decreed tithe for the poor.

And R' Elazar ben Azariah — decreed second tithe.

Who has the burden of proof?

R' Yishmael

R' Yishmael challenged R’ Elazar ben Azariah to prove his stricter position, saying the burden of proof is on him (עליו ראיה ללמד).

אמר רבי ישמעאל:

אלעזר בן עזריה!

עליך ראיה ללמד,

שאתה מחמיר,

שכל המחמיר —

עליו ראיה ללמד

R' Yishmael said:

Elazar ben Azariah!

you must produce your proof

because you are expressing the stricter view

and whoever expresses a stricter view —

has the burden to produce the proof

R' Elazar ben Azariah

But R’ Elazar ben Azariah argued that R’ Tarfon's view, deviating from the sequence of years, required justification, and the burden of proof is on him.

אמר לו רבי אלעזר בן עזריה:

ישמעאל אחי!

אני לא שניתי מסדר השנים,

טרפון אחי שנה,

ועליו ראיה ללמד

R' Elazar ben Azariah said to him:

Yishmael, my brother!

I have not deviated from the sequence of years,

Tarfon, my brother, has deviated from it

and the burden is upon him to produce the proof.

Geographical Comparison Arguments: Is Ammon and Moab more analogous to Egypt, or to Babylonia?

R' Tarfon

R' Tarfon reasoned that, like Egypt, which is outside Israel and gives the tithe for the poor in the seventh year to support Israel’s poor, Ammon and Moab should do the same.

השיב רבי טרפון:

מצרים — חוץ לארץ,

עמון ומואב — חוץ לארץ

מה מצרים — מעשר עני בשביעית,

אף עמון ומואב — מעשר עני בשביעית

R' Tarfon answered:

Egypt — is outside the land of Israel,

Ammon and Moab — are outside the land of Israel

just as Egypt — must give tithe for the poor in the seventh year,

so must Ammon and Moab — give tithe for the poor in the seventh year.

R' Elazar ben Azariah

R' Elazar ben Azariah countered by comparing Ammon and Moab to Babylon, which gives the second tithe.

השיב רבי אלעזר בן עזריה:

בבל — חוץ לארץ,

עמון ומואב — חוץ לארץ

מה בבל — מעשר שני בשביעית,

אף עמון ומואב — מעשר שני בשביעית

R' Elazar ben Azariah answered:

Babylon — is outside the land of Israel,

Ammon and Moab — are outside the land of Israel:

just as Babylon — must give second tithe in the seventh year,

so must Ammon and Moab — give second tithe in the seventh year.

R' Tarfon

R’ Tarfon emphasized proximity of Ammon/Moab to Israel, claiming it justified giving to the poor.

אמר רבי טרפון:

מצרים —

שהיא קרובה,

עשאוה מעשר עני,

שיהיו עניי ישראל נסמכים עליה בשביעית,

אף עמון ומואב —

שהם קרובים,

נעשים מעשר עני,

שיהיו עניי ישראל נסמכים עליהם בשביעית

R' Tarfon said:

on Egypt —

which is near,

they imposed tithe for the poor

so that the poor of Israel might be supported by it during the seventh year;

so on Ammon and Moab —

which are near,

we should impose tithe for the poor

so that the poor of Israel may be supported by it during the seventh year.

R' Elazar ben Azariah (Malakhi 3:8)

R’ Elazar ben Azariah warned that neglecting the second tithe would rob God and harm the people, citing Malakhi 3:8.

אמר לו רבי אלעזר בן עזריה:

הרי אתה כמהנן ממון,

ואין אתה אלא כמפסיד נפשות

קובע אתה את השמים מלהוריד טל ומטר,

שנאמר (מלאכי ג):

"היקבע אדם אלהים?

כי אתם קבעים אתי,

ואמרתם:

במה קבענוך?

המעשר והתרומה"

R' Elazar ben Azariah said to him:

Behold, you are like one who would benefit them with gain,

yet you are really as one who causes them to perish.

Would you rob the heavens so that dew or rain should not descend?

As it is said,

"Will a man rob God?

Yet you rob me.

But you:

How have we robbed You?

In tithes and heave-offerings" (Malakhi 3:8).

R' Yehoshua's Intervention Re Precedent

R' Yehoshua intervened, suggesting the debate should rely on newer precedents.

אמר רבי יהושע:

הריני כמשיב על טרפון אחי,

אבל לא לענין דבריו

R' Joshua said:

Behold, I shall be as one who replies on behalf of Tarfon, my brother,

but not in accordance with the substance of his arguments.

New vs. Old

מצרים — מעשה חדש,

ובבל — מעשה ישן,

והנדון שלפנינו — מעשה חדש.

ידון מעשה חדש ממעשה חדש,

ואל ידון מעשה חדש ממעשה ישן

The law regarding Egypt — is a new act

and the law regarding Babylon — is an old act,

and the law which is being argued before us — is a new act.

A new act should be argued from [another] new act,

but a new act should not be argued from an old act.

Elders vs. Prophets

מצרים — מעשה זקנים,

ובבל — מעשה נביאים,

והנדון שלפנינו — מעשה זקנים.

ידון מעשה זקנים ממעשה זקנים,

ואל ידון מעשה זקנים ממעשה נביאים

The law regarding Egypt — is the act of the Elders (זקנים)

and the law regarding Babylon — is the act of the Prophets,

and the law which is being argued before us is the act of the Elders.

Let one act of the Elders be argued from [another] act of the Elders,

but let not an act of the Elders be argued from an act of the Prophets.

Final Resolution and Validation

Ultimately, the votes favored R’ Tarfon's position: Ammon and Moab give the tithe for the poor in seventh year, not second tithe.

נמנו וגמרו:

עמון ומואב —

מעשרין מעשר עני בשביעית

The votes were counted and they decided that

Ammon and Moab —

should give tithe for the poor in the seventh year.

R' Yose ben Durmaskit4 later informed R' Eliezer in Lod, who affirmed5 that the ruling aligns with a tradition passed from R' Yohanan ben Zakkai, ultimately going back all the way to a law give to Moses at Sinai (הלכה למשה מסיני), confirming that Ammon and Moab give the tithe for the poor during the seventh year.

וכשבא רבי יוסי בן דרמסקית אצל רבי אליעזר בלוד,

אמר לו: מה חדוש היה לכם בבית המדרש היום?

אמר לו:

נמנו וגמרו:

עמון ומואב —

מעשרים מעשר עני בשביעית

And when R' Yose ben Durmaskit visited R' Eliezer in Lod

he said to him: what new thing did you have in the house of study today?

He said to him:

their votes were counted and they decided that

Ammon and Moab —

must give tithe for the poor in the seventh year.

בכה רבי אליעזר ואמר:

“סוד ה' ליראיו

ובריתו להודיעם” (תהלים כה).

צא ואמר להם:

אל תחשו למנינכם.

מקבל אני מרבן יוחנן בן זכאי,

ששמע מרבו,

ורבו מרבו

עד הלכה למשה מסיני,

שעמון ומואב —

מעשרין מעשר עני בשביעית

R' Eliezer wept and said:

"The counsel of YHWH is with them that fear him:

and his covenant, to make them know it" (Psalms 25:14).

Go and tell them:

Don't worry about your voting.

I received a tradition from R' Yohanan ben Zakkai

who heard it from his teacher,

and his teacher from his teacher,

and so back to a halachah given to Moses from Sinai,

that Ammon and Moab —

must give tithe for the poor in the seventh year.

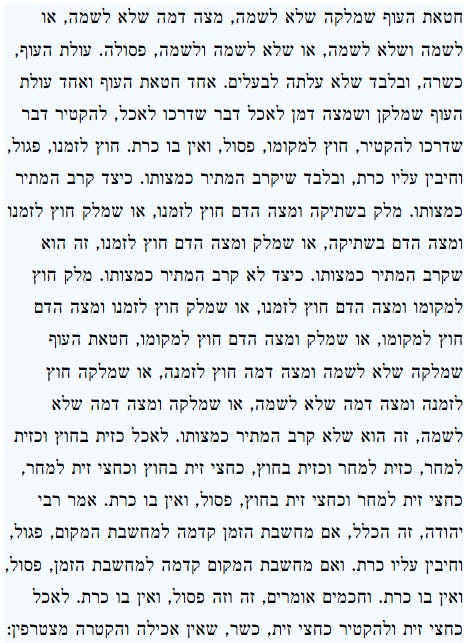

Appendix 1 - Flowchart visualization that shows the logical progression of the debate in Mishnah Yadayim 4:3

The visualization illustrates the logical flow of the debate in Mishnah Yadayim 4:3.

Each sage is color-coded for clarity, and the diagram shows how the debate progresses from initial positions through various types of reasoning before reaching its conclusion. The flow illustrates the sophisticated reasoning processes used in Talmudic debate, combining legal, geographical, practical, spiritual, and traditional considerations.

This visualization reveals how the Mishnah doesn't simply state a law, but shows the process by which the sages arrived at their conclusion through reasoned debate and validation through tradition.

Here's how the diagram works:

Starting Point: The diagram begins with the central question about what law applies to Ammon and Moab in the seventh year.

Diverging Initial Positions: The flow then branches into the two opposing positions:

R' Tarfon argues for tithe for the poor (מעשר עני)

R' Elazar ben Azariah argues for second tithe (מעשר שני)

Burden of Proof Debate: The first layer of argumentation focuses on who carries the burden of proof:

R' Yishmael claims R' Elazar must prove his position as it's stricter

R' Elazar responds that R' Tarfon must prove his position as it deviates from the sequence of years

Geographical Comparisons: Both sages then support their positions with geographical analogies:

R' Tarfon compares Ammon/Moab to Egypt (supports tithe for the poor)

R' Elazar compares Ammon/Moab to Babylon (supports second tithe)

Pragmatic vs. Spiritual Arguments: The debate then shifts to different types of reasoning:

R' Tarfon uses a practical argument about proximity to Israel and supporting the poor

R' Elazar uses a spiritual argument citing scripture about robbing God

Methodological Intervention: R' Yehoshua intervenes with meta-reasoning about which precedents should apply:

New precedents should be derived from new precedents (favoring Egypt comparison)

Elder rulings should be derived from elder rulings (again favoring Egypt comparison)

Resolution: The flow converges to show:

The final vote supporting R' Tarfon's position (tithe for the poor)

R' Eliezer's traditional validation that this ruling aligns with tradition from Moses at Sinai

Appendix 2 - Top Ten Longest Mishnah Sections

Tractate Chapter Mishnah Character Count6

Sotah 9:157 - 1242

Yadayim 4:38 - 1195

Eduyot 6:39 - 1171

Tamid 4:310 - 1078

Kiddushin 4:1411 - 1052

Sanhedrin 10:312 - 1005

Nazir 8:113 - 939

Sanhedrin 4:514 - 848

Nedarim 3:1115 - 843

Zevachim 6:716 - 829

רבי יוסי בן דרמסקית - meaning, “son of the Damascene woman”.

Adding a biblical phrase: “סוד ה' ליראיו“, understood to mean “God’s secret (סוד - in the late biblical/Mishnaic Hebrew sense of “secret”, as opposed to the Classical Biblical sense of “counsel”) is with those that fear him”, a phrase that is later used in the Talmud as well for expressing divine insight or knowledge granted to the rabbinic sages, often in the context of validating halachic rulings or secret traditions passed through generations.

The Mishnah says that said this while weeping (בכה רבי אליעזר ואמר). For similar phenomenon of dramatic crying by sages elsewhere in talmudic literature, see my piece here:

בכה רבי שמעון ואמר:

R' Shimon cried and said:

And here:

בכה רבן יוחנן בן זכאי ואמר:

Rabban Yoḥanan ben Zakkai cried and said:

This appears in many other places as well. From a literary perspective, the motif of sages weeping in the Talmud serves multiple narrative and rhetorical functions.

1. Emotional and Dramatic Heightening The act of weeping is a powerful emotional signal that amplifies the gravity of the moment. The crying of a sage, a revered figure known for wisdom and composure, adds an emotional layer, illustrating the depth of their inner turmoil or the profound weight of the situation. It elevates the speech that follows into something more than a rational declaration—it becomes a visceral, heartfelt expression, as seen in the examples of R’ Shimon ben Yohai and Rabban Yoḥanan ben Zakkai. In both cases, weeping is a prelude to a significant statement, enhancing its emotional resonance.

2. Symbol of Vulnerability: Although sages are typically portrayed as paragons of wisdom and strength, their weeping portrays them in a more vulnerable and human light. This vulnerability allows readers to connect with the sages on a deeper emotional level and underscores that even the greatest minds grapple with overwhelming existential or spiritual dilemmas. For instance, R' Shimon bar Yohai's weeping over the absence of a divine miracle for himself, compared to a mere servant's experience, exposes his personal struggle with divine favor, while Rabban Yoḥanan ben Zakkai's weeping conveys his anguish over the impending destruction of the Temple.

3. Transition to Revelation: Weeping often precedes moments of revelation or divine intervention in these stories. It marks the sages' recognition of a deeper truth or acceptance of a harsh reality, acting as a gateway to spiritual insight. For instance, in Rabbi Eliezer's case, his tears lead into the revelation of a tradition passed down from Moses at Sinai, reaffirming divine authority. Yoḥanan ben Zakkai's weeping is an acceptance of a harsh reality. The tears serve as a bridge between human emotion and divine knowledge, emphasizing that profound insight often comes at the cost of emotional struggle.

Regarding talmudic anecdotes of sages displaying strong emotions, consider the instances of sages becoming upset in the rainmaking stories, discussed in my three-part series, with the final installment here. In these accounts, the phrase "חלש דעתיה" — “he became upset” (literally: “his mind weakened”) — appears in three of the stories.

It’s notable, and likely not a coincidence, that a significant percentage of these Mishnah sections pertain to Temple sacrifices. (The reason may be due to inherent literary structure in those sections, or due to later editorial choices.)

See my discussion of this Mishnah section here: “"On Whom Can We Rely?” Literary Laments of a Fallen Society in the Mishnah (Mishnah Sotah 9:15)“.

Screenshot of how it looks in Sefaria:

Screenshot of how it looks in Sefaria:

Screenshot of how it looks in Sefaria (see my visualization of the literary structure of this Mishnah at my piece on literary structure, at my Academia page)::

See my discussion of the latter part of this Mishnah section here: “Pt1 From Donkey Drivers to Doctors, Bloodletters to Tanners: Rabbinic Insights and Guidance on Professions (Mishnah Kiddushin 4:14; Talmud ibid., 82a-b)“, section “Mishnah (Kiddushin 4:14)“.

See my discussion of this Mishnah section here: “Barred from the Afterlife: Heretics, Biblical Sinners, and Groups Denied a Share in the World-to-Come (Mishnah Sanhedrin 10:1-4)“.

Screenshot of how it looks in Sefaria:

See my discussion of this Mishnah section here: “Pt2 The First Man: Talmudic Reflections on Adam's Creation (Sanhedrin 38a-39b)“, section “Appendix - Court-Mandated Witness Intimidation in Capital Cases (Mishnah Sanhedrin 4:5 = Sanhedrin 37a)“.

See my visualization of the literary structure of the latter half of this Mishnah section at my piece on literary structure, at my Academia page, section “7 Statements on Circumcision (Nedarim Chapter 3:11b)” (Mishnah_Nedarim.3.11).

Screenshot of how it looks in Sefaria: